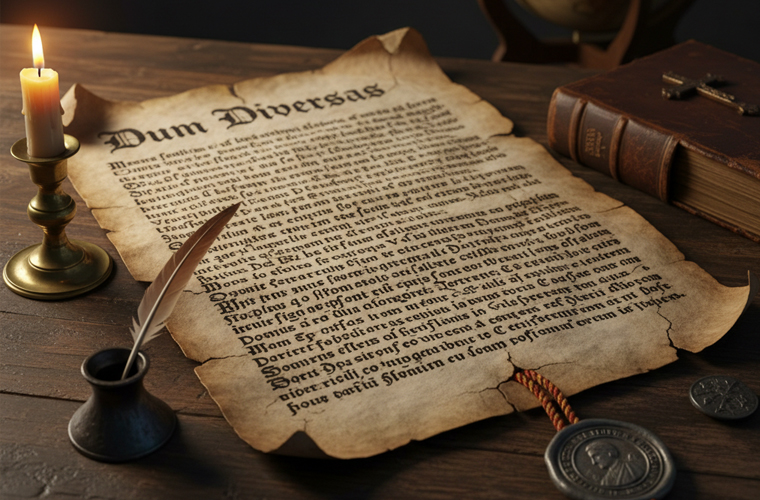

In the annals of ecclesiastical history, few documents carry the weight of moral and geopolitical consequence as Dum Diversas, a papal bull issued on June 18, 1452, by Pope Nicholas V. Addressed to King Afonso V of Portugal, this decree—whose Latin title translates to “While Different”—granted sweeping authority to conquer, subjugate, and enslave non-Christians, particularly Muslims and pagans encountered along the African coast. Far from a mere religious edict, Dum Diversas served as a foundational pillar of the European Age of Exploration, fueling colonial expansion, the transatlantic slave trade, and the so-called Doctrine of Discovery. Its legacy endures in debates over reparations, indigenous rights, and the Catholic Church’s reckoning with its imperial past.

The mid-15th century was a pivotal era for Europe, marked by the waning of the Crusades and the dawn of maritime exploration. Portugal, under the energetic leadership of Prince Henry the Navigator, was aggressively probing West Africa’s shores, driven by ambitions to bypass Muslim-controlled trans-Saharan trade routes for gold, ivory, and spices. These expeditions often clashed with Islamic traders and local kingdoms, framing encounters as holy wars against “infidels.”

Pope Nicholas V, born Tommaso Parentucelli in 1397, ascended to the papacy in 1447 amid a fractured Christendom. A humanist scholar and patron of the arts—he founded the Vatican Library and supported Renaissance figures like Lorenzo Valla—Nicholas sought to consolidate papal authority while advancing the faith. His pontificate emphasized missionary zeal, but it also navigated realpolitik: Portugal’s explorations promised to enrich Catholic monarchs and expand Christianity’s reach, countering Ottoman advances in the East. Dum Diversas emerged from this nexus, responding to Afonso V’s request for papal sanction of Portugal’s African ventures.

Dum Diversas is concise yet explosive in its language, blending spiritual imperatives with temporal permissions. The bull praises Afonso’s “holy and praiseworthy purpose” in exploring “remote and unknown” lands, then escalates to explicit authorization:

“We grant you [Afonso V] full and free permission to invade, search out, capture, and subjugate the Saracens and pagans and any other unbelievers and enemies of Christ wherever they may be, as well as their kingdoms, duchies, counties, principalities, and other property […] and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery.”

This decree targeted “Saracens” (a medieval term for Muslims) and “pagans” (non-Christians), framing conquest as a divine mandate. It invoked just war theory, allowing the seizure of lands and goods, and the enslavement of captives as “perpetual servitude.” While not explicitly naming Africa, its geographic scope was “unlimited,” applying to newly discovered territories. Historians like Wilhelm Grewe have called it the most significant papal act for Portuguese colonization, as it morally justified force and trade in slaves to undermine Muslim monopolies.

The bull’s rhetoric echoed earlier Crusader bulls but was innovated by tying enslavement to exploration, transforming missionary outreach into a license for exploitation. Issued just months before Portugal’s capture of key West African outposts, Dum Diversas ignited a chain reaction. It emboldened Portuguese explorers to raid coastal villages, establishing forts like Elmina Castle (1482) as hubs for the slave trade. By the 1460s, thousands of Africans were shipped to Europe annually, marking the genesis of the Atlantic slave trade.

This bull was quickly supplemented: In 1455, Nicholas issued Romanus Pontifex, extending rights to trade monopolies and missionary control. Pope Calixtus III’s Inter Caetera (1456) reaffirmed these privileges. Collectively, they formed the bedrock of the Doctrine of Discovery—a legal and theological framework later cited by Spain, England, and others to claim indigenous lands in the Americas and beyond.

The edict’s influence rippled through centuries. It informed the 1493 bull Inter Caetera by Alexander VI, which divided the New World between Spain and Portugal, and echoed in U.S. Supreme Court rulings like Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823), which upheld Native dispossession. In Africa, it facilitated the subjugation of millions, contributing to the demographic devastation of the continent. By the 17th century, cracks appeared: In 1686, the Holy Office decreed freedom for Africans enslaved in unjust wars, implicitly critiquing Dum Diversas. Yet formal reckoning lagged. Indigenous activists, including those at the United Nations, long demanded its revocation, viewing it as a root of ongoing inequities.

In a landmark shift, on March 30, 2023, the Vatican issued a statement formally repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery, declaring the 15th-century bulls—including Dum Diversas—as failing to “reflect the equal dignity and rights of Indigenous peoples” and never part of core Catholic teaching. The document acknowledged how these texts were “manipulated” for colonial gain, though it stopped short of rescinding the bulls themselves or admitting institutional culpability. Critics, including Indigenous leaders, hailed it as progress but urged deeper atonement, such as land returns and reparations.

Today, Dum Diversas symbolizes the perils of intertwining faith and empire. It prompts reflection on how religious authority can sanctify injustice, and underscores the Church’s evolving stance on human rights. As global dialogues on decolonization intensify, this 1452 decree remains a stark reminder of history’s long shadow. Dum Diversas was no footnote; it was a catalyst for conquest that reshaped the world. From the shores of West Africa to the courts of Europe and the halls of the Vatican, its echoes persist, challenging us to confront the past’s complicities in the present’s inequalities. In an era of reconciliation, understanding this bull is essential—not just for historians, but for anyone committed to a more equitable future.