The transatlantic slave trade can be understood through the experiences of a single enslaved person who endured a series of catastrophic events that, by design, severed him or her from home, family, and nearly all things familiar. Capture in the African interior, transport to the coast, sale to slave traders, the passage in a slave ship, and sale and enslavement in the Americas tested the spirit and will of resilient men, women, and children who struggled to find meaning and happiness in a New World dependent upon their labor and coercion.

The transatlantic slave trade can also be understood through its sheer magnitude: for 366 years, European slavers loaded approximately 12.5 million Africans onto Atlantic slave ships. About 11 million survived the Middle Passage to landfall and life in the Americas.

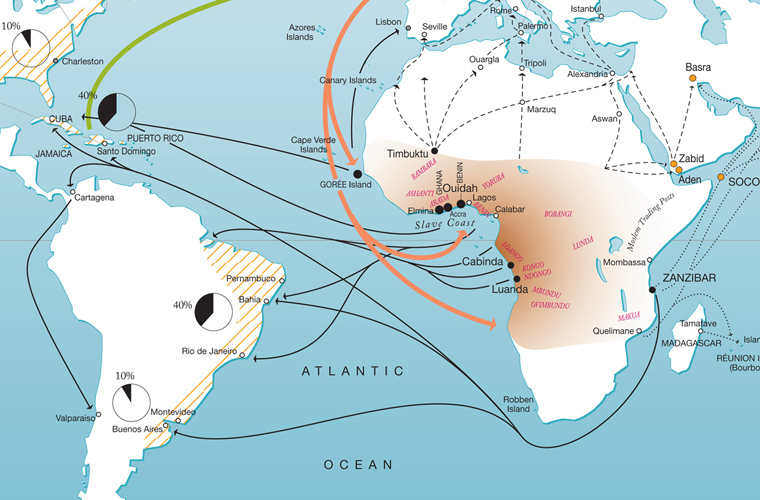

The transatlantic slave trade was an oceanic trade in African men, women, and children which lasted from the mid-sixteenth century until the 1860s. European traders loaded African captives at dozens of points on the African coast, from Senegambia to Angola and around the Cape to Mozambique. The great majority of captives were collected from West and Central Africa and from Angola.

The trade was initiated by the Portuguese and Spanish, especially after the settlement of sugar plantations in the Americas. European planters spread sugar, cultivated by enslaved Africans on plantations in Brazil, and later Barbados, throughout the Caribbean. In time, planters sought to grow other profitable crops, such as tobacco, rice, coffee, cocoa, and cotton, with European indentured laborers as well as African and Indian slave laborers. Nearly 70 percent of all African laborers in the Americas worked on plantations that grew sugar cane and produced sugar, rum, molasses, and other byproducts for export to Europe, North America, and elsewhere in the Atlantic world.

Before the first Africans arrived in British North America in 1619, more than half a million African captives had already been transported and enslaved in Brazil. By the end of the nineteenth century, that number had risen to more than 4 million. Northern European powers soon followed Portugal and Spain into the transatlantic slave trade. The majority of African captives were carried by the Portuguese, Brazilians, British, French, and Dutch. British slave traders alone transported 3.5 million Africans to the Americas.

The transatlantic slave trade was complex and varied considerably over time and place, but it had far-reaching and lasting consequences for much of Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Asia. First, it was a trade between European and African slavers who victimized millions of African men, women, and children. Second, the profits gained by Americans and Europeans from the slave trade and slavery made possible the development of economic and political growth in major regions of the Americas and Europe.

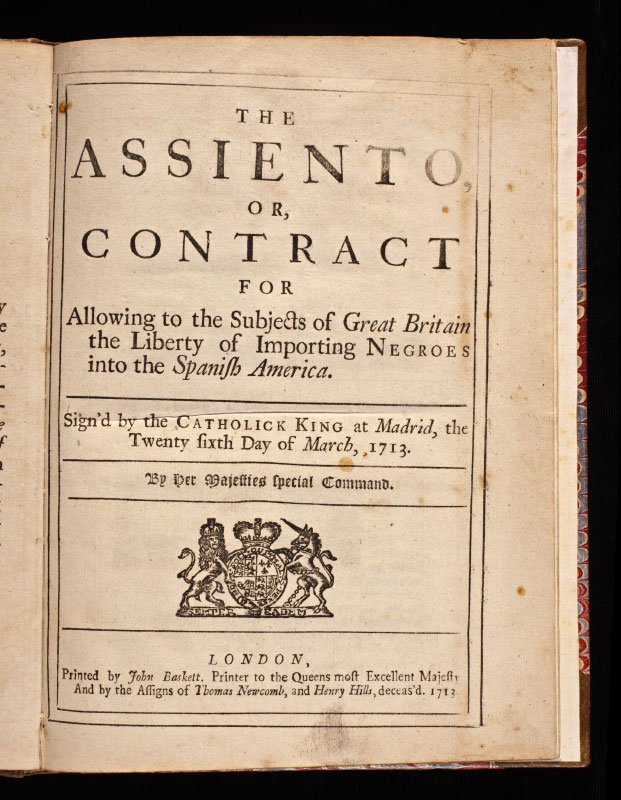

Europeans used various methods to organize the Atlantic trade. Spain licensed (by Asiento agreements) other nations to supply its Spanish American and Caribbean colonies with African captives. France, the Netherlands, and England initially used monopoly companies. In time, the demand for African laborers in the Americas was met by more open trade which allowed other merchants to engage in trade with Africans. Thus, formidable private trading companies emerged, such as Britain’s Royal African Company (1660–1752) and the Dutch West India Company of the Netherlands (1602–1792).

Such companies operated in major ports to construct, finance, insure and organize slave ships and their cargoes. The profits generated from the Atlantic trade economically and politically transformed Liverpool and Bristol in England, Nantes, and Bordeaux in France, Lisbon in Portugal, Rio de Janeiro and Salvador de Bahia in Brazil, and Newport, Rhode Island, in the United States. Each port developed links to a wide hinterland for local and international goods in Asia and the capital to sustain the trade in African captives.

European merchants and ship captains (followed later by those from Brazil and North America) packed their sailing vessels with local goods and commodities from Asia to trade on the African coast. African traders made specific demands for European goods in exchange for African captives. Enslaved Africans, their often violent capture and enslavement out of sight of the European general public, were exchanged for iron bars and textiles, luxury goods, cowrie shells, liquor, firearms, and other products that varied region by region over time.

Much of the wealth generated by the transatlantic slave trade supported the creation of industries and institutions in modern North America and Europe. To an equal degree, profits from slave trading and slave-generated products funded the creation of fine art, decorative arts, and architecture that continues to inform aesthetics today.