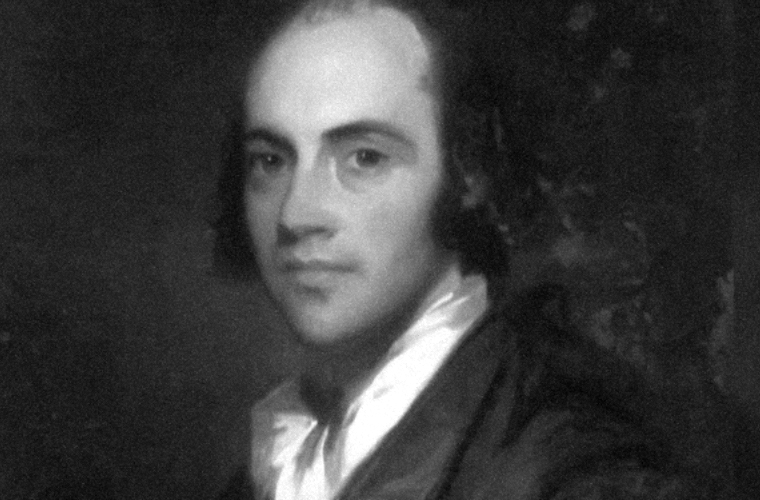

Though he never attained the highest office of his adopted country, few of America’s founders influenced its political system more than Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804). Born in the British West Indies, he arrived in the colonies as a teenager and quickly embarked on a remarkable career. He was a member of the Continental Congress, an author of the Federalist Papers, a champion of the Constitution and the first secretary of the Treasury, where he helped found the first national bank, the U.S. Mint and a tax collection bureau that would later become the U.S. Coast Guard. Troubled by personal and political scandals in his later years, Hamilton was shot and killed in one of history’s most infamous duels by one of his fiercest rivals, the then Vice President Aaron Burr, in July 1804.

Born in the West Indies, Hamilton moved to the mainland in 1772 and entered King’s College (now Columbia University) the following year. By 1774 he was speaking at public meetings and writing revolutionary essays, and in 1776 he became a captain of the artillery. After taking part in the Battle of Long Island and the retreat from New York City, he joined Washington’s staff in 1777, where he remained until February 1781. He commanded a battery of artillery at the Battle of Yorktown.

As secretary of the Treasury Hamilton’s great achievement was funding the federal debt at face value, which rectified and nationalized the financial chaos inherited from the Revolution. But he accomplished still more. He was responsible for creating the First Bank of the United States on the model of the Bank of England, and his Report on Manufactures fostered commercial and industrial development in the new nation. He also played a significant role in generating the Washington administration’s policy of unfriendly neutrality toward the French Revolution and in establishing a rapprochement with Britain.

Hamilton’s policies and actions provoked intense opposition, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Just as Hamilton and Madison had collaborated in the Federalist movement during the 1780s, so Jefferson and Madison now collaborated against Hamilton’s Federalist party in the 1790s. The result was division, both within the Washington administration and in the country as a whole. After Hamilton left the Treasury in 1795 to practice law, he continued to be active in Federalist politics, but he was deeply critical of the presidency of John Adams. Nonetheless, at Washington’s insistence, he was made inspector general of the army during the Quasi-War with France in 1798.