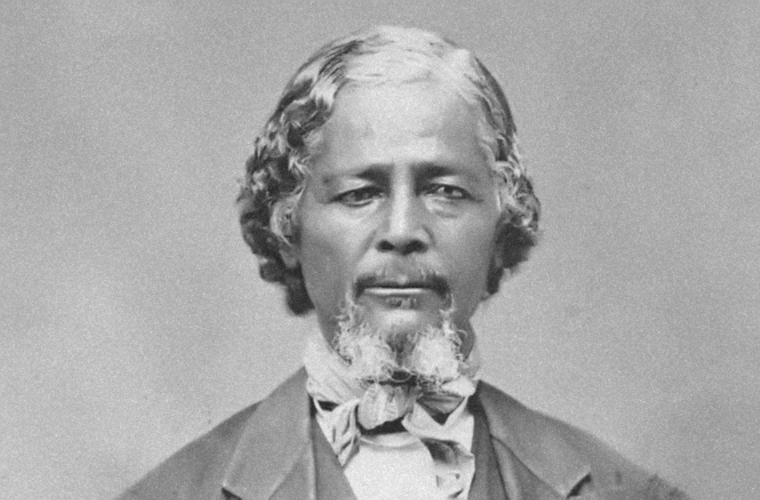

Benjamin “Pap” Singleton was an African American man who played an important part in the massive emigration of ex-slaves from the South to the West. Although he was not the single source of inspiration for the black exodus from the South, Singleton did play a significant role in helping blacks escape the oppressive social climate of the South following the Civil War (1861–65; a war fought between the Northern and Southern United States over the issue of slavery) and find greater opportunities in the West.

As is true with many ex-slaves, there are precious few documents recording Singleton’s life. Other than a record of his birth in 1809, little is known about him prior to the great exodus of blacks from Tennessee to Kansas, which occurred when Singleton was in his seventies. It is known that as a slave he was sold to various owners in the Gulf States (Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas), but he escaped several times. He fled to Canada and Detroit, Michigan, but returned to Tennessee after the Civil War. There is evidence that Singleton spent most of his life working as a cabinetmaker in Edgefield, Tennessee, near Nashville.

When President Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, blacks in the South were legally freed from slavery. This began a chain of events that would eventually lead to a great migration of blacks from the southern states to the western frontier. Although free, blacks had a very difficult time earning a living in southern states because of severe discrimination and limited opportunities available to minorities. Moreover, whites and blacks vied for the precious, fertile southern land. The South struggled to adjust to changing political and social circumstances, particularly the demise of slavery. Some whites told blacks that the Emancipation Proclamation would be voided and that blacks would be returned to slavery. White landowners sometimes refused to pay blacks for their labor until a year had passed. This practice trapped blacks in unfair labor agreements and made them like indentured servants. As freed blacks tried to secure land for themselves, many became discouraged by the lack of opportunity in the South and hoped for more independent, prosperous lives.

Land for his people

In 1869 Singleton organized the Tennessee Real Estate and Homestead Association in hopes of helping blacks acquire and settle land in the South. When this venture proved unsuccessful—mainly because whites refused to sell productive land to blacks at fair prices—Singleton began giving speeches promoting the idea that migration out of the South was the best way for blacks to prosper. In the West, he reasoned, blacks would be treated more fairly. Western laws favored equal opportunity and the land was abundant there. Singleton imagined self-sufficient black communities where African Americans could live free from the oppression they faced in the South. Singleton and others felt that if blacks owned businesses and participated in social institutions, there would be more opportunities for the entire black population to prosper. Singleton looked to Kansas for better opportunities.

The welfare of the black community was foremost in Singleton’s mind. He took his leadership role seriously, believing himself to be an instrument of God. In his testimony before the Select Committee of the United States Senate to Investigate the Causes of the Removal of the Negroes from the Southern States to the Northern States in 1880, Singleton explained that “I have taken my people out in the roads and in the dark places, and looked to the stars of heaven and prayed for the Southern man to turn his heart.” However, when the whites did not “turn” their hearts, Singleton vigorously promoted the idea of an exodus. “[W]e are going to learn the South a lesson,” he added, according to Nell Irvin Painter in Exodusters. In 1873 Singleton’s first trip attracted more than three hundred blacks, who followed Singleton to Cherokee County, where the emigrants bought about one thousand acres of land.

Nicodemus, Kansas

Nicodemus (located along U.S. Route 24, two miles west of the Rooks-Graham county line) was the most famous black community and the last surviving colony founded by the Exodusters. The name “Nicodemus” came from a slave who, according to legend, predicted the coming of the Civil War.

Established in 1877–1878, Nicodemus was home to seven hundred African Americans by 1880, and the population continued to grow until 1910. In the beginning, settlers lived in dugouts or sod houses and shared three horses to break the frontier soil. One man even used a cow to pull his plow. The best times in Nicodemus came in the mid-1880s when plentiful rain provided lush crops and rumors of a potential railroad station circulated. The community held special celebrations on Emancipation Day. Each summer, a square mile of land contained a jubilant carnival with sports and games. The Nicodemus Blues became one of the first black baseball teams in 1907, and the great black baseball player Satchell Paige was a member of the team for a while. Nicodemus became a national historic landmark in 1976, a tribute to its black homesteaders.

Buoyed by the success of the first trip, Singleton and his associates formed the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association by 1874 to further promote the migration of blacks westward. In 1876 Singleton began investigating the possibility of mass emigration. In a letter to the governor of Kansas quoted in Painter’s Exodusters, Singleton asked whether blacks could purchase land over a period of time because many could not afford to buy land immediately.

During the following two years, Singleton worked diligently to promote migration to Kansas. In 1877, he traveled there to inspect possible locations for settlement and ran a notice in the Nashville newspaper describing his willingness to discuss opportunities in Kansas real estate. At meetings sponsored by the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association, Singleton urged his audience to start “looking after the interest of our downtrodden race,” according to Painter. By 1878 Singleton established a second colony at Dunlap in Morris County, Kansas. He printed handbills reading “Ho for Kansas!” that announced the departure dates of the expeditions to Kansas. The association held festivals and picnics to promote migration. Between 1877 and 1879, the group led more than twenty thousand blacks to Kansas.

Ho for Kansas!

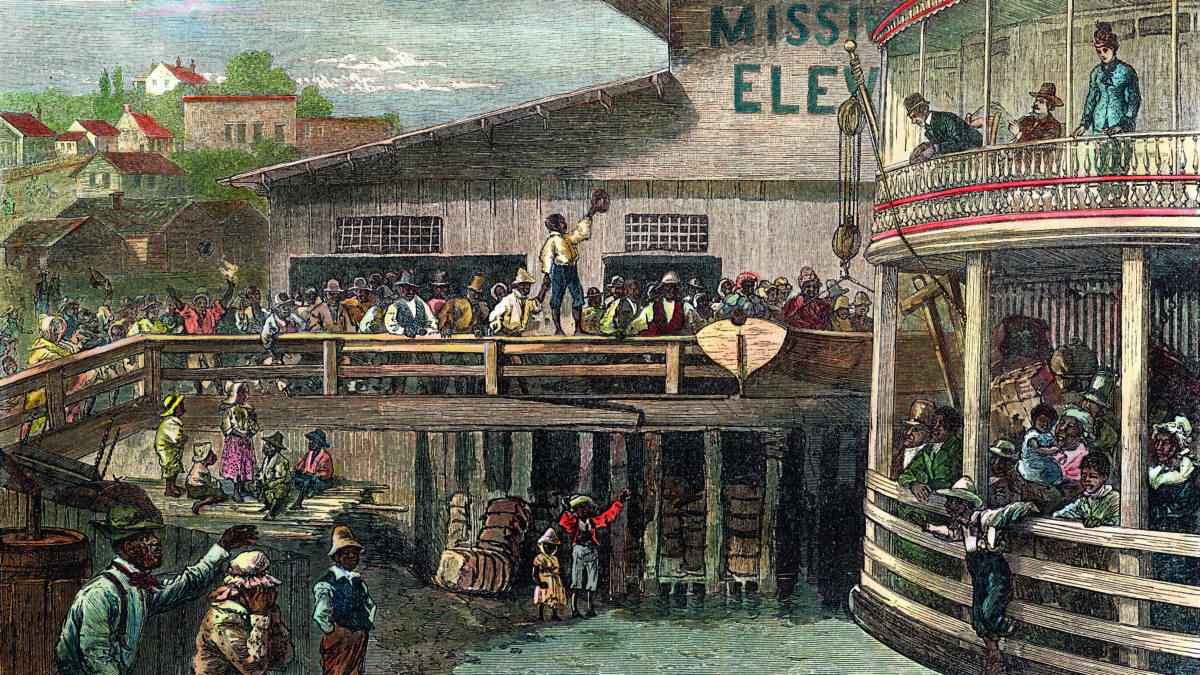

Kansas was the most popular destination for blacks leaving the South. Between 1879 and 1881 approximately sixty thousand blacks migrated to Kansas in search of social and economic freedom The most well-known settlement of blacks in Kansas was Nicodemus, a colony established through Singleton’s efforts. Settled by migrants from Kentucky in 1877 and 1878, Nicodemus grew to a population of seven hundred people by 1880. Other black settlements included some in Hodgeman, Barton, Rice, and Marion Counties. By 1879 these black communities were thriving, and the black population in the southern states was sufficiently primed for mass migration. “Come West, Come to Kansas,” newspapers urged. The Colored Citizen printed advice columns detailing how and where to settle in Kansas. Many papers printed the following article, quoted in Painter’s Exodusters:

One thousand Negroes will emigrate this season from Hinds and Madison counties, Miss., to Kansas. We hope they will better their condition, and send back so favorable a report from the “land of promise” that thousands will be induced to follow them, and the emigration will go on till the whites will have a numerical majority in every county in Mississippi.

The Great Exodus

Though migration had been steady since the early 1870s, the Kansas Fever Exodus of 1879 was the largest single movement of blacks. Thousands of emigrants moved to Kansas seeking their fortune and escaping oppression. A black Texan named C. P. Hicks to best described why African Americans were determined to leave the South in his letter to Governor St. John of Texas in 1879. Quoted in Exodusters, the letter reads as follows:

There are no words which can fully express or explain the real condition of my people throughout the south, nor how deeply and keenly they feel the necessity of fleeing from the wrath and long pent-up hatred of their old masters which they feel assured will ere long burst loose like the pent-up fires of a volcano and crush them if they remain here many years longer.

However, no one could pin down the exact reasons for the “simultaneous stampede,” as the Chicago Tribune called it. “It is one of those cases where the whole thing seemed to be in the air, a kind of migratory epidemic.”

Father of the exodus?

Singleton is credited with bringing thousands of blacks to Kansas during the late 1800s and is often referred to as the “Father of the Colored Exodus.” Claiming responsibility for the mass migration, Singleton announced in the senate hearing in 1880, as quoted in Exodusters: “Right emphatically, I tell you today, I woke up the millions right through me! The great God of glory has worked in me. I have had open-air interviews with the living spirit of God for my people, and we are going to leave the South.”

However, Singleton was not the only catalyst for the migration. Henry Adams, a thirty-six-year-old ex-slave, garnered recognition as another leader of the exodus. Though Adams is often given as much credit as Singleton, the two never met or corresponded. S. A. McClure, A. W. McConnell, and W. A. Sizemore also worked with Singleton to inspire and escort blacks to Kansas. In addition to these men, countless others also promoted the idea of emigration. Rumors spread throughout the black community of free transportation to Kansas and free supplies for Kansas land. Blacks organized conventions to discuss the opportunities in Kansas and sent delegates to investigate the details of the journey.

The social climate of the South also helped promote the idea of emigration. When federal troops withdrew from the South in 1877, Reconstruction (1865–77; the period after the Civil War when the federal government controlled the South before readmitting it to the Union) officially ended. Blacks then faced racial oppression in the South through segregation laws and the terrorist activities of groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

Activist slows down

From mid-1879 to 1880, Singleton settled at his colony at Dunlap. The Topeka Daily Blade quoted Singleton as saying “I am now getting too old, and I think it would be better to send someone more competent that is identified with the emigration,” according to Painter. Though Singleton reduced the number of settlers he personally conducted to Kansas, he remained dedicated to his mission to help his people and retained his passion for the movement.

Singleton forms more organizations to help blacks

By 1881, Singleton had organized the United Colored Links, a group interested in uniting colored people for the purpose of improving their lives. However, the United Colored Links disbanded after their first convention. Frustrated by the failure of the group to unite under a common cause, Singleton decided to rally them again. According to Painter, Singleton announced in the North Topeka Times in 1883 that he had been “instructed by the spirit of the ‘Lord’ to call his people together to unite them from their divided condition.” As he aged, he participated in more organizations that encouraged the migration of blacks out of the South. In 1883, Singleton founded the Chief League, which encouraged blacks to move to the island of Cyprus in the Mediterranean Sea. Later, in 1885, he formed the Trans-Atlantic Society, which encouraged blacks to return to their ancestral homeland in Africa. By 1887 the group disbanded. Singleton died in St. Louis in 1892.

Although Singleton’s work attracted much attention, the effect on the regional distribution of the total black population was minor. When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, less than 8 percent of all blacks lived in the Northeast or Midwest. After the Civil War, the black population in the Northeast fell slightly, while the percentage rose in the Midwest. By 1900, the U.S. Census reported that 90 percent of all blacks remained in the South.

Kansas did not turn out to be the land of opportunity many had hoped for. The influx of so many blacks strained the state’s resources in the mid-1880s, and some of the black communities developed into little more than refugee camps. Yet by 1900 blacks in Kansas were generally better off than those in the South. Blacks enjoyed more freedoms in the West. However, they discovered that nowhere in the United States could black escape racism. In cities, schools were racially segregated, and some white Kansans resented the increasing population of blacks in the state. Nevertheless, many of the Exodusters succeeded in finding a place where they could live more freely than they had in the South.