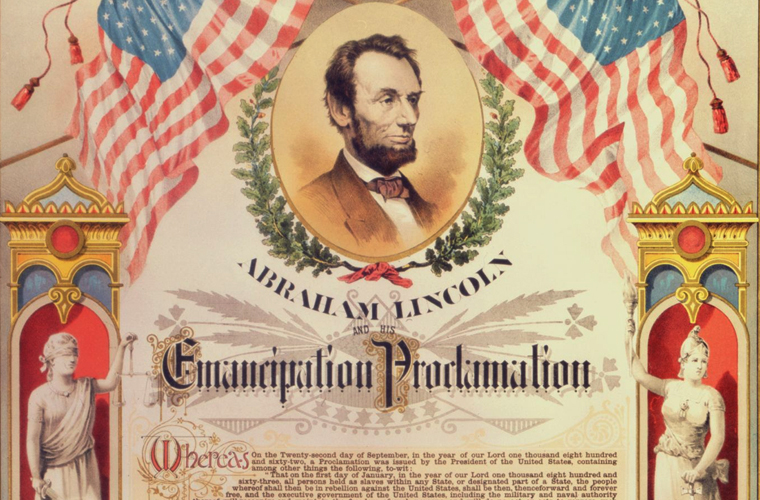

When the American Civil War (1861-65) began, President Abraham Lincoln carefully framed the conflict as concerning the preservation of the Union rather than the abolition of slavery. Although he personally found the practice of slavery abhorrent, he knew that neither Northerners nor the residents of the border slave states would support abolition as a war aim. But by mid-1862, as thousands of slaves fled to join the invading Northern armies, Lincoln was convinced that abolition had become a sound military strategy, as well as the morally correct path. On September 22, soon after the Union victory at Antietam, he issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that as of January 1, 1863, all slaves in the rebellious states “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” While the Emancipation Proclamation did not free a single slave, it was an important turning point in the war, transforming the fight to preserve the nation into a battle for human freedom.

Slavery was “an unqualified evil to the negro, the white man, and the State,” said Abraham Lincoln in the 1850s. Yet in his first inaugural address, Lincoln declared that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the States where it exists.” He reiterated this pledge in his first message to Congress on July 4, 1861, when the Civil War was three months old.

What explains this apparent inconsistency in Lincoln’s statements? And how did he get from his pledge not to interfere with slavery to a decision a year later to issue an emancipation proclamation? The answers lie in the Constitution and in the course of the Civil War. As an individual, Lincoln hated slavery. As a Republican, he wished to exclude it from the territories as the first step to putting the institution “in the course of ultimate extinction.” But as president of the United States, Lincoln was bound by a Constitution that protected slavery in any state where citizens wanted it. As commander in chief of the armed forces in the Civil War, Lincoln also worried about the support of the four border slave states and the Northern Democrats. These groups probably would have turned against the war for the Union if the Republicans had made a move against slavery in 1861.

But the president’s role as commander in chief cut two ways. If it restrained him from alienating proslavery Unionists, it also empowered him to seize enemy property used to wage war against the United States. Slaves were the most conspicuous and valuable such property. They raised food and fiber for the Southern war effort, worked in munitions factories, and served as teamsters and laborers in the army. Gen. Benjamin Butler, commander of Union forces occupying a foothold in Virginia at Fortress Monroe on the mouth of the James River, provided a legal rationale for the seizure of slave property. When three slaves who had worked on rebel fortifications escaped to Butler’s lines in May 1861, he declared them contraband of war and refused to return them to their Confederate owner.

Most Republicans had become convinced by 1862 that the war against a slaveholders’ rebellion must become a war against slavery itself, and they put increasing pressure on Lincoln to proclaim an emancipation policy. This would have comported with Lincoln’s personal convictions, but as president, he felt compelled to balance these convictions against the danger of alienating half of the Union constituency. By the summer of 1862, however, it was clear that he risked alienating the Republican half of his constituency if he did not act against slavery.

Moreover, the war was going badly for the Union. After a string of military victories in the early months of 1862, Northern armies suffered demoralizing reverses in July and August. The argument that emancipation was a military necessity became increasingly persuasive. It would weaken the Confederacy and correspondingly strengthen the Union by siphoning off part of the Southern labor force and adding this manpower to the Northern side. In July 1862 Congress enacted two laws based on this premise: a second confiscation act that freed slaves of persons who had engaged in rebellion against the United States, and a militia act that empowered the president to use freed slaves in the army in any capacity he saw fit—even as soldiers.

By this time Lincoln had decided on an even more dramatic measure: a proclamation issued as commander-in-chief freeing all slaves in states waging war against the Union. As he told a member of his cabinet, emancipation had become “a military necessity…. We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued…. The Administration must set an example, and strike at the heart of the rebellion.” The cabinet agreed, but Secretary of State William H. Seward persuaded Lincoln to withhold the proclamation until a major Union military victory could give it added force. Lincoln used the delay to help prepare conservative opinions for what was coming.

In a letter to journalist Horace Greeley, published in the New York Tribune on August 22, 1862, the president reiterated that his “paramount object in the struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery.” If he could accomplish this objective by freeing all, some, or none of the slaves, that was what he would do. Lincoln had already decided to free some and was in effect forewarning potential opponents of the Emancipation Proclamation that they must accept it as a necessary measure to save the Union. In a publicized meeting with black residents of Washington, also in 1862, Lincoln urged them to consider emigrating abroad to escape the prejudice they encountered and to help persuade conservatives that the much-feared racial consequences of emancipation might be thereby mitigated.

One month later, after the qualified Union victory in the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation warning that in all states still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, he would declare their slaves “then, thenceforward, and forever free.” January 1 came and with it the final proclamation, which committed the government and armed forces of the United States to liberate the slaves in rebel states “as an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity.” The proclamation exempted the border slave states and all or parts of three Confederate states controlled by the Union army on the grounds that these areas were not in rebellion against the United States.

Lincoln had tried earlier to persuade the border states to accept gradual emancipation, with compensation to slave owners from the federal government, but they had refused. The proclamation also authorized the recruitment of freed slaves and free blacks as Union soldiers; during the next 2 1/2 years 180,000 of them fought in the Union army and 10,000 in the navy, making a vital contribution to Union victory as well as their own freedom. Emancipation would vastly increase the stakes of the war. It became a war for “a new birth of freedom,” as Lincoln stated in the Gettysburg Address, a war that would transform Southern society by destroying its basic institution.

Meanwhile Lincoln and the Republican party recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation, as a war measure, might have no constitutional validity once the war was over. The legal framework of slavery would still exist in the former Confederate states as well as in the Union slave states that had been exempted from the proclamation. So the party committed itself to a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery. The overwhelmingly Republican Senate passed the Thirteenth Amendment by more than the necessary two-thirds majority on April 8, 1864. But not until January 31, 1865, did enough Democrats in the House abstain or vote for the amendment to pass it by a bare two-thirds. By December 18, 1865, the requisite three-quarters of the states had ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which ensured that forever after “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude … shall exist within the United States.”