The unanimous decision, upholding the right of whites and blacks to sell residential property to one another, was the first exception to state segregation laws sanctioned under Plessy v. Ferguson (1898). Hailed by the public at the time as upholding personal rights as well as property rights, Buchanan v. Warley is now seen by legal commentators as a precursor to Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

The 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision broke “the backbone of segregation,” sociologist W. E. B. du Bois recalled gratefully 20 years later, even though Jim Crow still ruled public education and transportation.

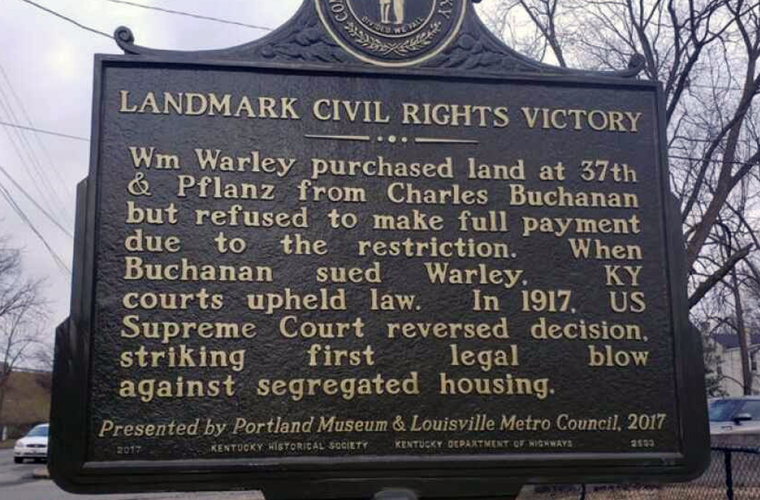

The test case was brought by a white real estate agent after a black civil rights activist refused to pay full price for a house lot. A Louisville, Kentucky, ordinance prohibiting blacks from moving into white neighborhoods made the lot less valuable, William Warley, the activist, claimed. The result was a “landmark decision in modest dress,” stated the late constitutional scholar, Alexander M. Bickel of Yale. The decision “breathed life into Reconstruction principles,” Bickel observed, building “a constitutional foundation for the belated principles of racial justice that gathered momentum after World War II.”

Buchanan v. Warley was largely forgotten after Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. The 56 years between Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education had been assumed to be a “slough of despond for the constitutional rights of black people.” But, in fact, the 1917 decision was the first great triumph of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and was heralded at the time as “A Momentous Decision” by The Nation: “The Supreme Court has, once again, proven a true bulwark of the liberties and rights of the colored population of the United States.”

Before World War I, starting in Baltimore, border and “upper South” states passed local residential segregation ordinances as blacks from the “deep South” began to migrate north. Coincidentally, local chapters of the newly formed NAACP were being created; and Warley, the president of the Louisville chapter, agreed to buy a house lot from Charles H. Buchanan, a friendly white real estate agent. Warley withheld $100 of the $250 price, however, because the ordinance did not allow him to “occupy said property as a residence.”

Buchanan sued and city attorneys, recognizing other laws could also be invalidated, joined the case on Warley’s ostensible behalf. Indeed, the North Carolina Appeals Court had struck down “so revolutionary a public policy,” citing the history of Celtic pales in Ireland and Jewish ghettoes in Russia. The Louisville ordinance, nevertheless, was upheld by the Kentucky Court of Appeals. Warley was represented before the Supreme Court by Moorfield Storey, a lawyer from Boston who, as a young abolitionist, participated in the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson after the Civil War.

Storey contended that the ordinance deprived African Americans of legal rights and had adverse social consequences for blacks, but not for whites. Storey, who was the first president of the NAACP, argued, “A law which forbids a Negro to rise does not forbid a white man to fall,” and it is “the common law right of every landowner to occupy his house or to sell or let it to whomever he pleases.”

The unanimous decision, written by Justice Day, described the ordinance as a “drastic measure . . . based wholly upon color, that and nothing more.” Day was a former secretary of state from Ohio who had negotiated the annexation of the Philippines and Puerto Rico after the Spanish-American War, which Storey had opposed as president of the Anti-Imperialist League. The two men did, however, share common New England abolitionist roots. Justice Day also found the ordinance served no public health or safety purpose and was not “essential to the maintenance of the purity of the races.” The judge observed under the ordinance “colored servants in white families are permitted, and nearby residences of colored persons.”

Storey worried that “the prejudice of some judges might lead them to dissent,” but the two Southern judges, Chief Justice White of Louisiana, a former Confederate soldier, and Justice McReynolds of Tennessee, concurred. Justice Holmes often called “the Yankee from Olympus” did draft a dissent, but not so much because of residential segregation concerns. Holmes suspected collusion between Buchanan, Warley, and the NAACP with the result that the case, consequently, was not “an honest and actual antagonistic assertion of rights.” He later shelved the dissent.

Buchanan v. Warley has been faulted as merely upholding property rights rather than affirming equal protection of personal rights under the law. It did, admittedly, encourage private restrictive covenants, which were not outlawed until the 1950s. Justice Day, in his decision, nevertheless, did cite “certain amendments” adopted after the Civil War “fixing certain fundamental rights which all are bound to respect” as guiding. He referred repeatedly to the Fourteenth Amendment as prohibiting the states from “depriving any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” Buchanan v. Warley clearly sent a signal, according to Bickel, “that in the second decade of the twentieth century Jim Crow no longer had a casual apologist in the Supreme Court of the United States.”