The Dixiecrats were a political party organized in the summer of 1948 by conservative white southern Democrats committed to states’ rights and the maintenance of segregation and opposed to federal intervention into the race, and to a lesser degree, labor relations. The Dixiecrats, formally known as the States’ Rights Democratic Party, were disturbed by their region’s declining influence within the national Democratic Party. The Dixiecrats held their one and only convention in Birmingham.

The roots of the Dixiecrat revolt lay in opposition to the New Deal policies, particularly the pro-labor reforms introduced by the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Wagner Act. The more immediate impetus for the movement, however, included President Harry Truman’s civil rights program, introduced in February 1948; the civil rights plank in the national Democratic Party’s 1948 presidential platform; and the unprecedented political mobilization of southern blacks in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Smith v. Allwright in 1944. In this Texas case, the Court ruled the white primary law violated the Fifteenth Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. The states of the Upper South acquiesced in the ruling, but the decision was a political bombshell in the Deep South. White legislators across the region sought ways to circumvent the ruling, and African Americans organized voter-registration campaigns. Across the South, more than a half-million African Americans registered to vote in the 1946 Democratic Party primaries.

The roots of the Dixiecrat revolt lay in opposition to the New Deal policies, particularly the pro-labor reforms introduced by the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Wagner Act. The more immediate impetus for the movement, however, included President Harry Truman’s civil rights program, introduced in February 1948; the civil rights plank in the national Democratic Party’s 1948 presidential platform; and the unprecedented political mobilization of southern blacks in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Smith v. Allwright in 1944. In this Texas case, the Court ruled the white primary law violated the Fifteenth Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. The states of the Upper South acquiesced in the ruling, but the decision was a political bombshell in the Deep South. White legislators across the region sought ways to circumvent the ruling, and African Americans organized voter-registration campaigns. Across the South, more than a half-million African Americans registered to vote in the 1946 Democratic Party primaries.

The Dixiecrat movement was strongest in southern states with large African American populations. In Alabama, the upheaval over Truman’s civil rights proposals to repeal the poll tax, enforce job anti-discrimination laws and make lynching a federal crime represented the latest reaction in a power struggle between the agricultural interests in the state’s Black Belt region and industrial conservatives and the New Deal liberals that had been going on since the 1930s and would continue into the next decade. The titular head of Alabama’s states’-rights forces was former governor Frank Dixon. Other prominent Alabamians who joined the Dixiecrats included state Democratic Party chairman Gessner T. McCorvey of Mobile; Birmingham attorney and political operative Horace Wilkinson; Birmingham public safety commissioner Eugene”Bull” Connor Walter Givhan, former head of the Alabama Farm Bureau; Sidney W. Smyer, a corporate lawyer from Birmingham and former lobbyist for the Associated Industries of Alabama; and textile magnate Donald Comer.

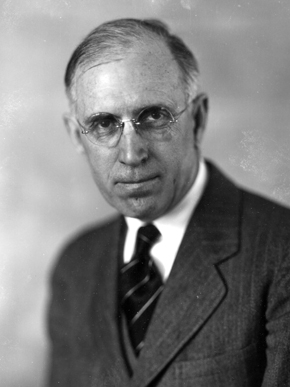

Gessner T. McCorvey

Gessner T. McCorvey

Uninterested in creating a new party from the grassroots, the Dixiecrats counted on their ability to control party machinery and to hijack the state Democratic Party. Chairman McCorvey turned Alabama’s early May primary into a states’-rights referendum. In addition to voting for candidates for local and state offices, voters also chose the state’s presidential electors and delegates to the upcoming July national convention. McCorvey asked all candidates for the elector to sign statements pledging to vote against any Democratic nominee who supported the entire civil rights program. Ultimately all of the chosen 11 electors signed the pledge. Alabama law permitted only the names of candidates supported by the state’s electors to appear on the ballot. At its national convention in July, the Democratic Party adopted a strong civil rights platform. In response, half of Alabama’s delegation stormed out in protest. Convention delegate George C. Wallace remained with the Alabama loyalists.

After the southern conservatives failed to prevent the nomination of Harry Truman at the 1948 Democratic National Convention, some 6,000 individuals from 13 southern states converged on Birmingham on July 17, 1948, to hold their own convention. Participants from South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi made up the majority of those in attendance. Governors J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Fielding Wright of Mississippi were nominated as the presidential and vice-presidential candidates of the States’ Rights Democrats. Their goal was to win the 127 electoral-college votes of the southern states, which would prevent either Republican Party nominee Thomas Dewy or Democrat Harry Truman from winning the 266 electoral votes necessary for election. Under this scenario, the contest would be decided by the House of Representatives, where southern states held 11 of the 48 votes, as each state would get only one vote if no candidate received a majority of electors’ ballots. In a House election, Dixiecrats believed that southern Democrats would be able to deadlock the election until one of the parties had agreed to drop its civil rights plank.

The Dixiecrats’ platform opposed federal anti-lynching and anti-poll tax legislation and a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission and pledged to uphold segregation and promote white supremacy. Their electoral success depended on their ability to convince the individual states to pledge their Democratic Party electors to the States’ Rights candidates. Alabama Dixiecrats had the least amount of work to do, as voters there had already bound their electors to oppose any civil rights candidate during the primary. On July 29, Alabama’s 11 Democratic Party electors convened and pledged their votes to Thurmond and Wright, essentially sealing the outcome of the presidential election in Alabama.

To the surprise of most Americans, Truman was elected president on November 2, 1948. The Dixiecrats carried Alabama, South Carolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana, where Thurmond and Wright were listed as the Democratic Party nominees. The party received only 39 electoral votes; too few to affect the outcome. The Dixiecrats’ victory in Alabama was relatively short-lived. In 1950, the states’ rights forces in Alabama lost control of the party to the national party loyalists.

Although the Dixiecrats have been dismissed as a failed third party, they were essential to southern political change. The Dixiecrat Party broke the South’s solid historical allegiance to the national Democratic Party and in doing so inaugurated an unpredictable era in which white southerners grappled with a variety of efforts to thwart racial progress. Dixiecrats were prominent members of the White Citizens Councils and other so-called Massive Resistance organizations dedicated to upholding segregation that flourished throughout the region in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the Dixiecrats as a political entity did not survive past 1948, white southerners used the movement’s organizational and intellectual framework to create new political institutions and new alliances in their desperate attempt to stymie racial progress and preserve power. Some Dixiecrats returned to the Democratic Party, and others, uncomfortable with the party’s civil rights position, voted as political independents in the presidential elections of the 1950s. Since the late 1940s, the term “Dixiecrat” has become a generic term used to describe white southern Democrats opposed to civil rights legislation.