Georgia Gilmore started the Club From Nowhere, a clandestine group that prepared and sold meals to raise money for the 381-day resistance action. It took all of Georgia Gilmore’s willpower not to explode at the driver of the crowded bus in Montgomery, Ala., one Friday afternoon in October 1955. She had just boarded and dropped her fare into the cash box when he shouted at her to get off and enter through the back door. “I told him I was already on the bus and I couldn’t see why I had to get off,” she recounted a year later at the trial of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as quoted in the book “Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott” (1997).

But after collecting herself, she complied and stepped off the bus. Before she could get back on, however, the driver sped off. Right then she vowed never to ride the buses again. Two months later, after another Montgomery bus rider, Rosa Parks, was arrested after refusing to give up her seat to a white man — a pivotal moment in the civil rights struggle — Gilmore resolved to join a community meeting at the Holt Street Baptist Church to talk about injustices toward African-Americans. She sensed that a movement was afoot.

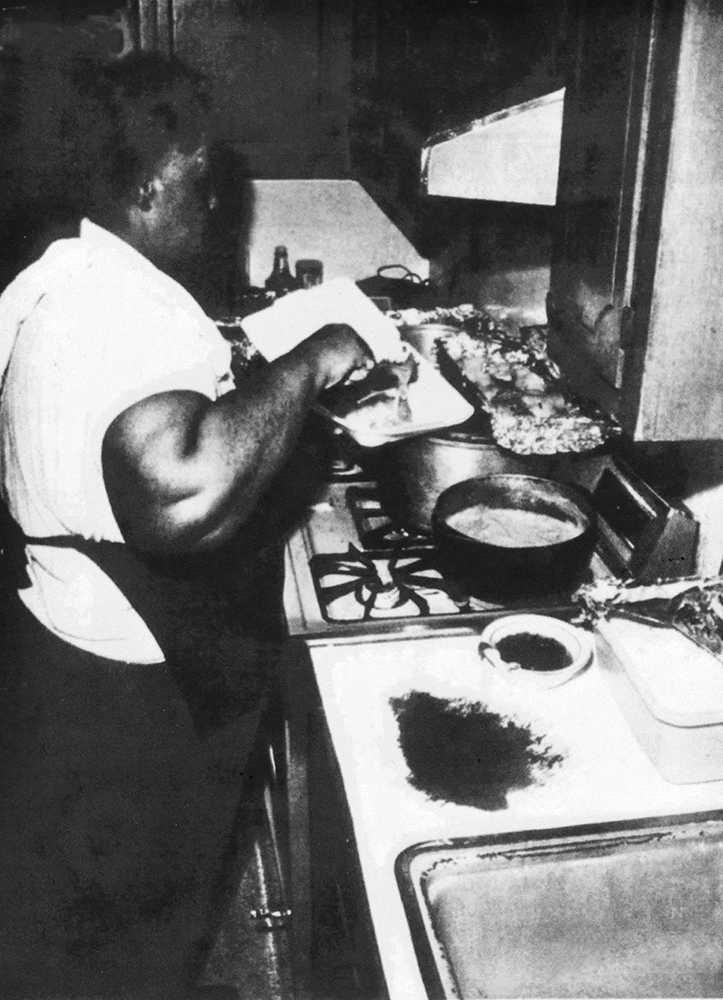

She was right. About 5,000 people came to the meeting, on Dec. 5, 1955, including King. They vowed not to ride the buses until their rights as equal citizens were recognized. Gilmore, who worked as a cook, decided she would use her culinary talents to feed and fund the resistance, which came to be known as the Montgomery Bus Boycott. She organized women to form the Club From Nowhere, a clandestine group that prepared savory meals (fried chicken sandwiches, fried fish, pork chops, greens, lima beans) and baked goods (peach pie, pound cakes) and sold them out of their homes, in local establishments and at protest meetings.

In a 1986 interview in “Eyes on the Prize,” the award-winning PBS documentary about the civil rights movement, Gilmore elaborated on the club and its name: “We decided that the peoples on the South Side would get a club, and the peoples on the West Side would get a club, and so we decided that we wouldn’t name the club anything, we’d just say it was the Club From Nowhere.”

The resistance lasted 381 days and involved weekly strategy sessions, protests, and an improvised carpool system with 300 cars and dozens of pickup and drop-off locations — all of which utilized the hundreds of dollars that the club raised. “You don’t hear Miss Gilmore’s name as often as Rosa Parks, but her actions were just as critical,” said Julia Turshen, the author of the cookbook “Feed the Resistance” (2017). “She literally fed the movement. She sustained it.” Black women were vital to keeping the boycott going, Gilmore said in the documentary, “because, you see, they were maids, cooks.”

“And they were the ones that really and truly kept the bus running,” she added. “And after the maids and the cooks stopped riding the bus, well, the bus didn’t have any need to run.”

Later in life, Gilmore started a catering business and home restaurant. While black people and white people usually ate in separate spaces, “they elbowed together in Gilmore’s kitchen,” the food historian John T. Edge wrote in the book “The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South” (2017). The Montgomery Advertiser

Later in life, Gilmore started a catering business and home restaurant. While black people and white people usually ate in separate spaces, “they elbowed together in Gilmore’s kitchen,” the food historian John T. Edge wrote in the book “The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South” (2017). The Montgomery Advertiser

Georgia Gilmore was born on Feb. 5, 1920, in Montgomery to Janie C. Gilmore and Taylor Burns. One of seven siblings, she grew up on a small family farm with hogs, cows, and chickens, which she took care of as a child, the food historian John T. Edge wrote in the book “The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South” (2017).

Gilmore’s incident on the bus was hardly the first time she faced racism. And it wasn’t the only time she would take action, Edge wrote. In 1957 the police arrested her son Mark Gilmore when he was passing through the whites-only neighborhood of Oak Park. She fought the charges, which were eventually dropped. Mark went on to become a longtime Montgomery city councilman. Another time, a white store clerk refused to sell her grandson a loaf of bread and a box of laundry detergent. So she marched to the counter, took the clerk’s pistol from him, and hit him with it.

“Gilmore was a big woman with a swaggering personality, who showed little fear in the face of white bigotry,” Edge wrote. Gilmore was working as a cook at the National Lunch Company when the boycott began. But in 1956, when a Montgomery County grand jury indicted King, she joined more than 80 people in testifying in his defense and was fired. Instead of searching for another job, she started a catering business and home restaurant. King, who lived a few blocks away, admired Gilmore’s drive, not to mention her pork chops, and gave her some money to equip her kitchen, Edge wrote.

“All these years you’ve worked for somebody else,” King told her, “now it’s time you worked for yourself.”

While black people and white people usually ate in separate spaces, “they elbowed together in Gilmore’s kitchen,” Edge wrote.

On Nov. 13, 1956, the United States Supreme Court struck down laws requiring segregated seating on public buses, and on Dec. 20, 1956, King called for the end of the boycott. “We felt that we had accomplished something that no one ever thought would ever happen in the city of Montgomery,” Gilmore said in “Eyes on the Prize,” “and being able to ride the bus and sit any place on the bus that you desire was something that hadn’t ever happened before.”

Gilmore’s activism continued. In December 1958, she was part of a class-action lawsuit to desegregate Montgomery’s public parks. Though segregation in the parks had been deemed unconstitutional by the district court, the practice had continued. Private segregated white schools, for instance, had been allowed to use public recreational facilities for football and baseball games, meaning that taxpayers were subsidizing segregated schools.

She made that argument in Georgia Theresa Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, in which the United States Supreme Court, in 1974, ruled the practice unconstitutional. Gilmore died on March 9, 1990, at 70. The cause was peritonitis, an inflammation of tissue in the abdomen. At her death she had been cooking food in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the march from Selma to Montgomery; the food was served to her mourners. Kia Damon, a chef in New York, said Gilmore was an inspiration for a project she started called the Supper Club From Nowhere, which focuses on food education and ancestral dishes.

“Even now she has such a big influence and impact on people like me,” Damon said, “and she was just a woman baking and cooking and saw something that needed to be done, and that resonated with me.” In a phone interview, Edge said a growing number of chefs of color are creating dishes that reflect their identities.

As he put it: “I think whether they’re aware of Georgia Gilmore’s story or not, that generation of people of color, of women of color, who do that work now and call themselves food activists — whether they are focused on food deserts, inequality, or no matter what it might be, environmental racism, whatever it might be — they are inheritors of the legacy and the boldness, and the best of them are the inheritors of the pragmatic boldness of Georgia Gilmore.”