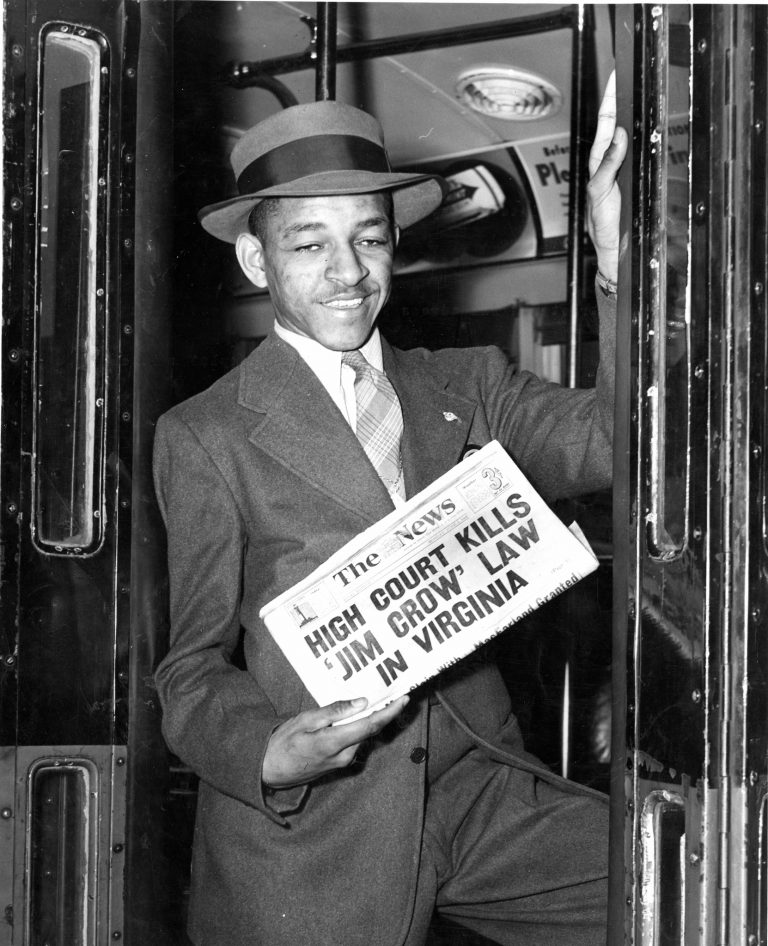

James H. Thomas, 23, of Washington D.C., boards an Arnold Bus at 12th & Pennsylvania Avenue NW for a trip to Virginia on June 4, 1946, the day after the Supreme Court ruling outlawing Jim Crow seating on interstate buses. The case, Morgan v. Virginia, originated in Essex County, Virginia.

James H. Thomas, 23, of Washington D.C., boards an Arnold Bus at 12th & Pennsylvania Avenue NW for a trip to Virginia on June 4, 1946, the day after the Supreme Court ruling outlawing Jim Crow seating on interstate buses. The case, Morgan v. Virginia, originated in Essex County, Virginia.

Virginia’s courts were in the national spotlight during the civil rights era. The NAACP filed more lawsuits in Virginia than in any other state, and many became nationally significant landmark cases. One of the five cases the U.S. Supreme Court ruled upon in Brown v. Board of Education, in 1954, was Davis v. Prince Edward County, a school segregation case that originated in Farmville in 1951. Green v. New Kent, decided in 1968, laid the foundation for school busing. Southern juries were desegregated as a result of Johnson v. Virginia in 1963, and Loving v. Virginia overturned laws in 17 states banning interracial marriage.

Leading the charge against Jim Crow was a team of talented NAACP lawyers, many of whom were from Virginia. Denied acceptance to segregated public law schools in Virginia, they attended Howard University School of Law in Washington D.D. In 1933 Oliver Hill, a native of Richmond, graduated second in his class at Howard, just behind Thurgood Marshall. Professor Charles Hamilton Houston, the vice-dean of the law school, mentored Marshall and Hill. When Houston left Howard University to become NAACP counsel in 1934, he recruited Marshall and Hill to join him in the fight against segregation.

Teacher salaries

Judge John J. Parker wrote the opinion for the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in Alston, et al. v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, et al., F2d 992, cert. denied, 311 U.S. 693 (1940), a milestone for the NAACP and the three attorneys who argued the case, Thurgood Marshall, William Hastie, and Oliver Hill. The court held that racially discriminatory teacher salary scales violated the rights of African American teachers under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

School children’s protest parade in Norfolk, Va., Sunday, June 25, 1939

School children’s protest parade in Norfolk, Va., Sunday, June 25, 1939

Melvin Alston, the plaintiff in the landmark case, and a teacher and principal of Booker T. Washington High School in Norfolk was the second choice of NAACP strategists seeking to bring a teacher salary equalization suit. They initially selected Alene Black, a chemistry teacher at Booker T. Washington. Black petitioned the Norfolk school board in the fall of 1939 and sued the board the following spring. When the board did not renew Black’s teaching contract for the 1939-1940 school year, she lost her status to sue and the lawsuit was dismissed. Thurgood Marshall and the Norfolk branch of the NAACP organized a protest parade, pictured above, to express opposition to Black’s dismissal.

Public transportation

The Journey of Reconciliation – first “Freedom Ride.” Participants stand outside the office of Attorney Spottswood W. Robinson, III, in Richmond, 1947. Left to right: Worth Handle, Wally Nelson, Ernest Bromley, Jim Peck, Igal Roodenko, Bayard Rustin, Joe Felmet, George Houser, and Andy Johnson holding suitcases and coats.

The Journey of Reconciliation – first “Freedom Ride.” Participants stand outside the office of Attorney Spottswood W. Robinson, III, in Richmond, 1947. Left to right: Worth Handle, Wally Nelson, Ernest Bromley, Jim Peck, Igal Roodenko, Bayard Rustin, Joe Felmet, George Houser, and Andy Johnson holding suitcases and coats.

The Supreme Court declared unconstitutional state laws mandating segregated interstate travel in Morgan v. Commonwealth, 328 U.S. 373 (1946), a case that originated in Essex County, Virginia. On July 16, 1944, Irene Morgan was traveling home to Baltimore after visiting her mother in Gloucester County. When additional riders boarded the bus near the town of Saluda, Morgan refused to give up her seat to a white passenger. She engaged in this spontaneous protest a decade before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in Montgomery, Alabama. NAACP and Richmond attorney Spottswood Robinson represented Morgan in her appeal. In 1947, the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized a bus ride to test the implementation of the Supreme Court ruling in Morgan. To educate the public about the case, riders chanted, “Get on the bus, sit anyplace/’Cause Irene Morgan won her case.”

School desegregation

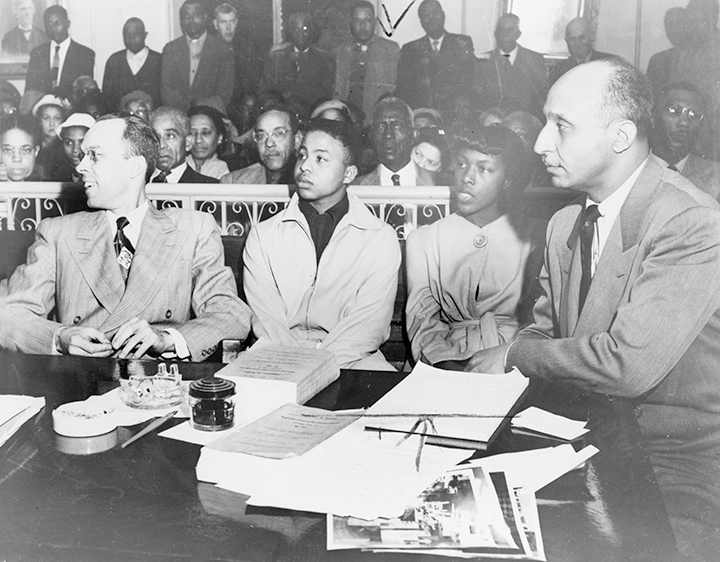

NAACP counsel and students witnessing questioning pursued by the King William County Commonwealth’s Attorney on February 5, 1953, in the circuit court, later decided in Commonwealth v. Dobbins, 198 Va. 697, 96 S.E.2d 154.

NAACP counsel and students witnessing questioning pursued by the King William County Commonwealth’s Attorney on February 5, 1953, in the circuit court, later decided in Commonwealth v. Dobbins, 198 Va. 697, 96 S.E.2d 154.

In 1950, the NAACP stopped suing for equal salaries and facilities and began to directly challenge the doctrine of “separate but equal.” In keeping with this change in strategy, in the fall of 1952 eight parents in the town of West Point, Va., refused to enroll their children in a segregated high school eighteen miles away in King William County. They were arrested for violating compulsory school attendance laws and appealed the conviction with representation from the same team that had represented Irene Morgan (Spottswood Robinson, Oliver Hill, and Marin A. Martin). By the time the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia issued an opinion on the case in 1957, the legal issue had already been decided by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education.

Mrs. Nettie Hunt, sitting on steps of Supreme Court holding newspaper, explaining to her daughter Nikkie the meaning of the Supreme Courts decision banning school segregation, 1954

Mrs. Nettie Hunt, sitting on steps of Supreme Court holding newspaper, explaining to her daughter Nikkie the meaning of the Supreme Courts decision banning school segregation, 1954

One of the five cases that comprised the Brown decision overturning segregation, Dorothy E. Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 103 F.Supp. 337 (1952), originated in Virginia on April 23, 1951, when 450 students walked out of Moton High School in Farmville to protest leaking roofs and poorly heated classrooms. Francis L. Griffin, the pastor of First Baptist Church in Farmville and president of the Moton Parent teachers Association, put the students in touch with NAACP lawyers Oliver Hill and Spottswood Robinson, in Richmond. The attorneys advised against litigation, but the students persisted and Robinson filed suit on their behalf in U.S. District Court in May 1951. When the Davis case came before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 1954, it was argued by Robinson and Thurgood Marshall, NAACP chief legal counsel.

Spottswood W. Robinson III (left), and NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, half-length portrait, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294, 1955, known as Brown II.

Spottswood W. Robinson III (left), and NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, half-length portrait, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294, 1955, known as Brown II.

In what became known as Brown II, the Supreme Court held that desegregation should proceed with “all deliberate speed,” but left the responsibility for developing a plan of implementation to local authorities and lower courts. Virginia’s political leadership responded by advocating massive resistance to the ruling. In August 1956, Governor Thomas Stanley convened a special session of the General Assembly to act on a package of school closing laws.

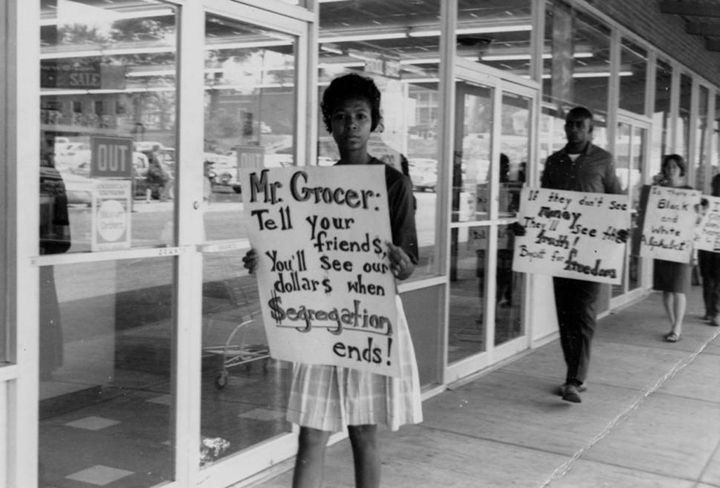

Protestors Darwyn White Dix, foreground) at W.T. Grant department store, Farmville, Va., August 24, 1963, a year before the Supreme Court held school closings unconstitutional in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218, 1964.

Protestors Darwyn White Dix, foreground) at W.T. Grant department store, Farmville, Va., August 24, 1963, a year before the Supreme Court held school closings unconstitutional in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218, 1964.

When federal judges ordered African American students admitted to schools in Warren County, Charlottesville, and Norfolk in September 1958, Governor Lindsay Almond ordered all nine schools, with a combined student population of 13,000, to shut their doors. Four months later, on January 19, 1959, both the U.S. District Court in Norfolk and the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia held the school closing laws unconstitutional, in James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (1959) and Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S.E. 2d (1959). Schools in Norfolk and Arlington were integrated without incident on February 2, 1959, ending the period of massive resistance at the state level.

Three NAACP Lawyers Involved in the Prince Edward School Litigation — They are (from left) Frank D. Reeves, Henry L. Marsh III, and S. W. Tucker. June 18, 1964.

In Prince Edward County, however, school board members dug in their heels and voted to close the schools for the 1959-60 school year, leaving approximately 1,700 students, mostly African American, without access to education. In June 1963, with the schools still closed and the issue unresolved by the courts, the membership of the state NAACP voted unanimously to endorse direct action protests. Members were advised to avoid businesses that practiced segregation and petition municipal governments for desegregation. Protests began in Farmville on July 25, 1963, and continued until September 16, 1963, when Governor Albertis Harrison, the Rev. Francis Griffin, and the Virginia NAACP reached a compromise agreement to open a temporary school in the fall.

Litigation against the Prince Edward County School Board was finally resolved on May 25, 1964, when the Supreme Court held in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County that the board’s decision to close the schools and issue vouchers to white students violated the rights of African American students under the Equal Protection Clause. On September 8, 1964, about 1,500 students, all but eight of whom were African American, attended classes in Prince Edward County public schools for the first time in five years. The battle to integrate the schools then shifted to freedom of choice plans. The Supreme Court ruled these plans unconstitutional in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), paving the way for court-mandated student busing plans to achieve integration.

Right to marry

After the Brown decision was delivered in 1954, anti-miscegenation laws banning marriage between people identified as white and African, Asian, and Native American were among the last bulwarks of segregation. Loving v. Virginia, 206 Va. 924, 147 S.E. 2d 89 (1966), reached Virginia’s high court in 1966. The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia upheld the statute and the case was appealed to the United States Supreme Court. In a unanimous opinion written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Supreme Court reversed the Virginia Court and stated that “We find the racial classifications in these statutes repugnant to the Fourteenth Amendment.”