Lucy Higgs Nichols was born in Halifax County, North Carolina on April 10, 1838. Lucy, along with her family, was held in chattel slavery by farmer Reubin Higgs. During this time, the Higgs family moved to Mississippi, then to Tennessee, taking Lucy and other enslaved people with them. In 1862, Lucy learned that she was to be moved south again, even further from freedom. Instead, she escaped with her young daughter, Mona, to the camp of the Indiana 23rd Volunteer Regiment. According to some sources, Lucy was accompanied by her husband as well, who was said to have died later after enlisting in the Union Army. Lucy managed to travel “some twenty or thirty miles” to the camp of the 23rd Regiment in Bolivar, Tennessee.

After making it to the camp of the Indiana 23rd Volunteer Regiment, Lucy was pursued by her former master. However, under the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862, she was able to beg protection from the regiment, who ensured that she would not be sent back to slavery. These acts declared that any property, including enslaved people, which was being used to aid the Confederate rebellion was to be seized by the federal government. The Confiscation Act of 1862 went even further in describing the new protected status of enslaved people, declaring that: “All slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all slaves of such person found on or being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterward occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.”

Although these acts were intended to deprive the Confederacy of labor, it was also a step towards emancipation, which thoroughly benefitted Lucy and her family and allowed her to escape slavery with the help of the 23rd Regiment. To show her gratitude to the Indiana 23rd Volunteer Regiment, Lucy, 30 years old at the time, “remained with the Twenty-third as a hospital nurse, cook, laundress and sewing woman.” She followed the regiment throughout the rest of the war, caring for soldiers on the front lines and on many long, arduous marches. Lucy was present at such critical battles as the Siege of Vicksburg and the Siege of Atlanta, then followed the 23rd Regiment through General William Tecumseh Sherman’s March to the Sea. Lucy even remained with the regiment after her daughter Mona, no older than five, died just after the surrender of Vicksburg. Mona was apparently well-loved by the soldiers and was given an “elaborate funeral” by the 23rd Regiment, as they covered her body with flowers and laid her to rest “in a long trench on the hillside above the city, where many a silent figure in blue was stretched out” in their own final resting places. Lucy was heartbroken and “left absolutely alone, but she still clung to the regiment.”

After the war, Lucy followed the 23rd Regiment to Washington, D.C., where she proudly marched with them as part of the “grand review of the Federal armies.” When the regiment was mustered out of service, the men invited her to return with them to New Albany, Indiana, where many of them were from. There, she was “employed as a servant in the families of several of the officers” of the 23rd Regiment. In 1870, she married laborer John Nichols, and they lived together on Nagel Street in New Albany until his death in 1910. After her husband’s death, Lucy remained in the city “as a border and a laundress.”

While living in New Albany, Lucy maintained contact with her fellow members of the 23rd Regiment. She attended every regimental reunion and marched in each Memorial Day parade. Lucy provided care for ill former troops, nursing them “as she did in war times,” while they cared for her in times of sickness and need as well, affectionately calling her “Aunt Lucy.” Lucy became a member of the New Albany chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization of veterans of the Union forces. Despite the remarkable recognition for her service by her immediate compatriots, Lucy was not recognized for her work as a Union Army nurse by the federal government. In 1892, Congress passed an act granting pensions to “all women employed by the Surgeon General of the Army as nurses, under contract or otherwise, during the late war of the rebellion” who were in need of financial assistance.

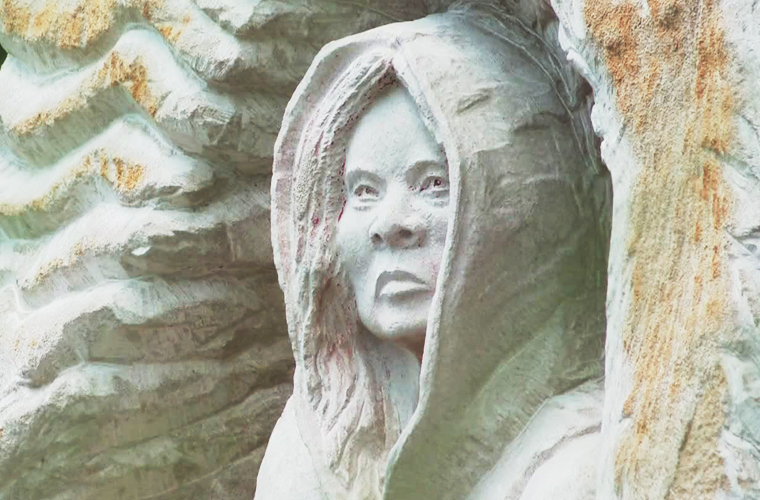

Lucy applied for a pension, citing medical issues which impacted her ability to work, but was rejected twice. Finally, in December 1898, a special act of Congress was passed and Lucy was approved for a $12 per month pension for the rest of her life. After the death of her husband John, Lucy was admitted to the Floyd County Poor Farm on January 5, 1915. She died there just weeks later, on January 29, 1915, and was buried with military honors in an unmarked grave in West Haven Cemetery in New Albany. The exact location of her grave is unknown because there was no written documentation and no tombstone. On July 3, 2019, a statue of Lucy Higgs Nichols and her daughter Mona was erected in New Albany, Indiana. It joined a 2011 state historical marker outside the Second Baptist Church, where Lucy was a member of the congregation. These monuments stand as a testament to her valor, from escaping slavery, to serving as a nurse on the front lines of the Civil War, to fighting for her right for compensation.

Unfortunately, Lucy Higgs Nichols was not the last black American veteran to be barred from receiving the benefits earned through their service. In 1944, Congress passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, popularly known as the G.I. Bill of Rights. This landmark legislation provided American veterans with four major entitlements: special job placement services, unemployment compensation, home, and business loans, and educational subsidies. While there was no language in the bill that definitively excluded black veterans on the basis of race, the G.I. Bill was unequally implemented to the benefit of white veterans. Black World War II veterans, especially those living in the south, experienced difficulties when they attempted to access the benefits due to them through the G.I. Bill, “because of a combination of racial discrimination and the poor administration of the bill’s benefits.” Like Lucy Higgs Nichols, many black veterans fought for their benefits after World War II, but many found that access was blocked by racist white administrators, and unlike Nichols, were unable to appeal their mistreatment.

An Indiana Historical Bureau historical marker, installed in 2011, in New Albany, Floyd County, commemorates Lucy Higgs Nichols’ life.