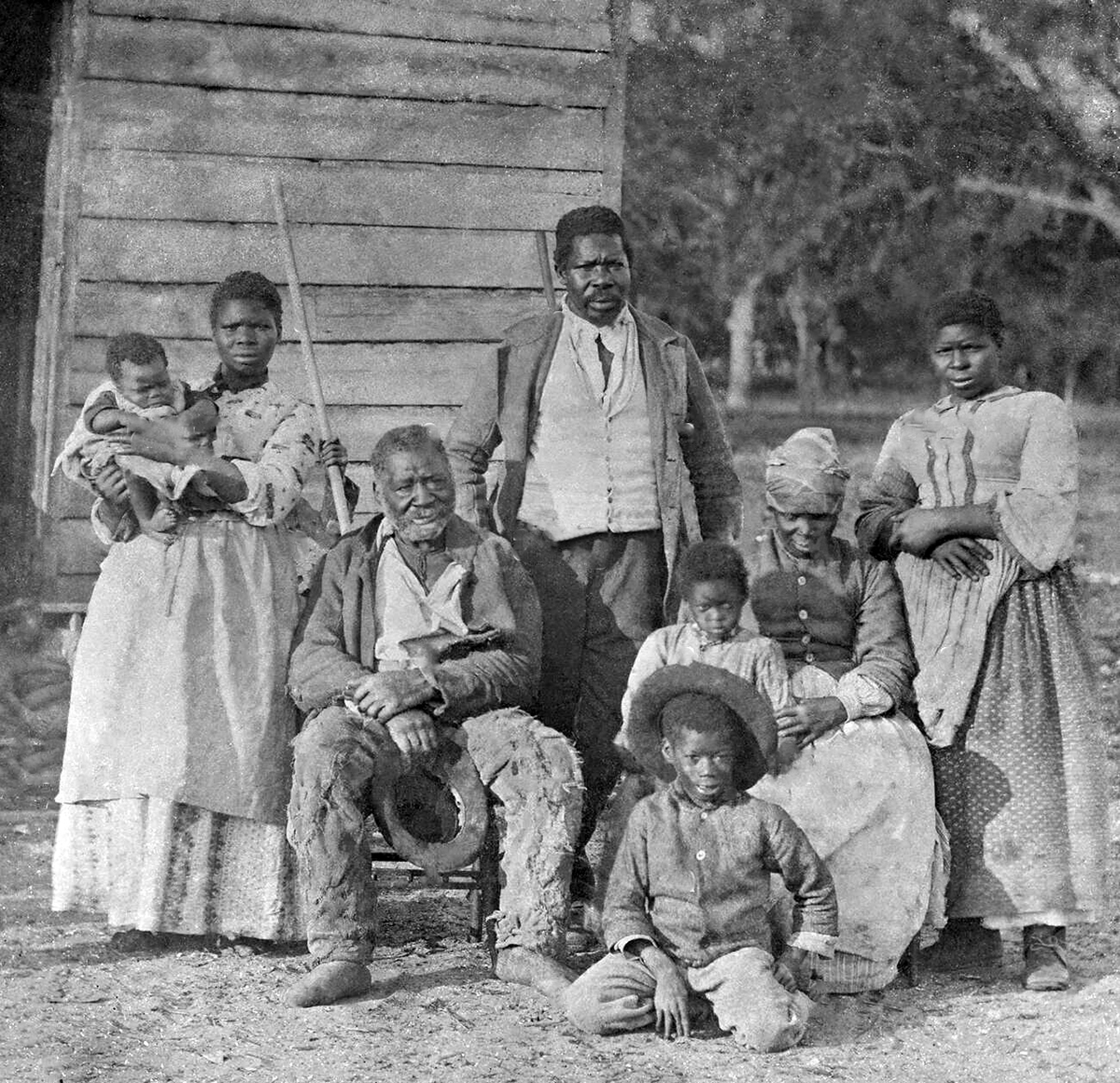

In the 17th century, Europeans began to establish settlements in the Americas. The division of the land into smaller units under private ownership became known as the plantation system. Starting in Virginia the system spread to the New England colonies. Crops grown on these plantations such as tobacco, rice, sugar cane, and cotton were labor-intensive. Slaves were in the fields from sunrise to sunset and at harvest time they did an eighteen-hour day. Women worked the same hours as the men and pregnant women were expected to continue until their child was born.

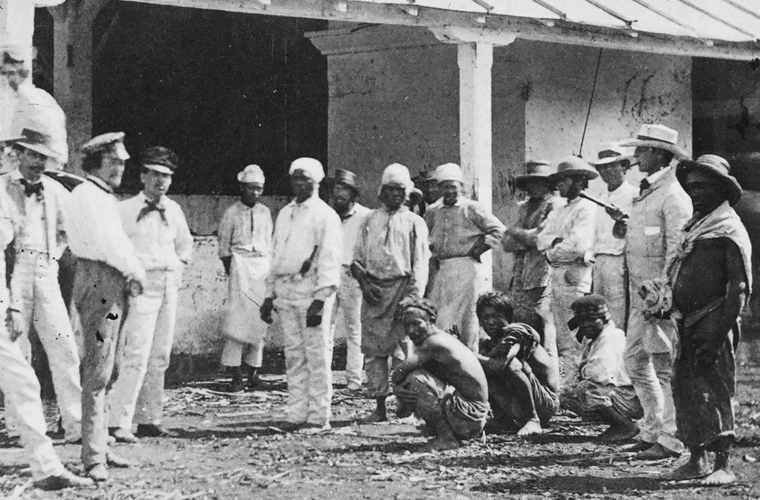

European immigrants had gone to America to own their own land and were reluctant to work for others. Convicts were sent over from Britain but there had not been enough to satisfy the tremendous demand for labor. Planters, therefore, began to purchase slaves. At first, these came from the West Indies but by the late 18th century they came directly from Africa, and busy slave markets were established in Philadelphia, Richmond, Charleston, and New Orleans.

The death rate amongst slaves was high. To replace their losses, plantation owners encouraged the slaves to have children. Child-bearing started around the age of thirteen, and by twenty the women slaves would be expected to have four or five children. To encourage child-bearing some population owners promised women slaves their freedom after they had produced fifteen children.

In the past, the South’s agricultural economy mainly survived thanks to the plantation system. Plantations were large farms that typically produced one staple crop. These crops could be rice, tobacco, cotton, sugar, or some other crop that was valuable to foreign buyers, as the South had an international economy. These large amounts of crops required a huge amount of labor to cultivate. Instead of paying workers to work the fields and adding more expenses for the landowners, they would instead buy slaves and conscript them into working the land. Because of the idea of slavery, plantation owners were able to essentially own the land, tools, and labor force, which eliminated most costs of running a farm. Because these costs were lowered, plantation owners were able to make vast amounts of profit, which is why the plantation system was the primary economic strategy for the South.

The plantation system was the main method of agricultural production in the South. The South had an international economy because they exported many of their products to the East in exchange for foreign credit, which allowed them to import goods from the East. Now, plantations were large farms that had 20 or more slaves and produced one staple crop. Some of these crops could be rice, cotton, tobacco, or maybe sugar. Such crops were labor-intensive to grow and harvest.

In other words, it took a large workforce, a large labor force, to grow and harvest these crops. Plantation owners made the system profitable by having slaves who were basically free labor. Now, we say “basically” free labor, because there was an initial cost for the slaves. They had to purchase them, and then they had to spend some money to house the slaves and feed them, but for the most part, they weren’t having to pay the daily wages that people would generally have to pay their employees.

Whenever you’re buying something, a lot of the cost of that item, most of the cost of that item, is just going to paying employees. With labor being free, this dramatically cut the cost of goods. Plantation owners thus owned the land, the tools, and the labor force. That’s how they made this whole process profitable. If it wasn’t for the free labor, it may have been hard to turn a profit on these crops. There are a few things just to remember. A plantation was a large farm, and it had 20 or more slaves, and it had one staple crop that it produced.