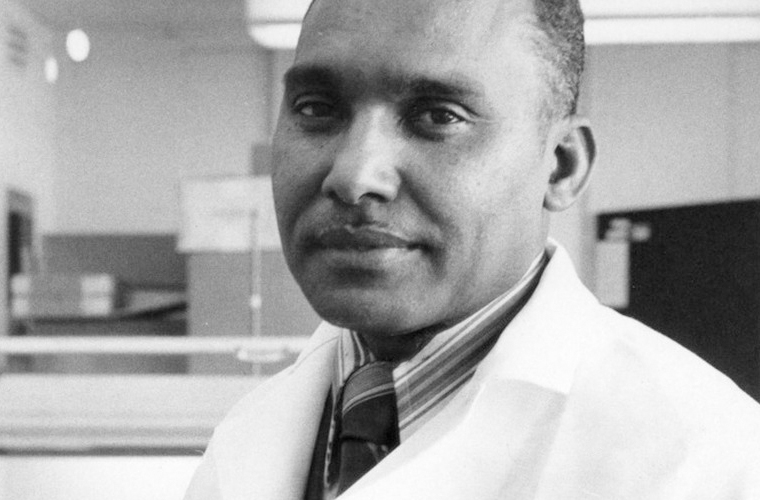

Samuel Lee Kountz Jr. was a physician and pioneer in organ transplantation, particularly renal transplant research and surgery. An Arkansas success story, he overcame the limitations of his childhood as an African American in the Delta region of a racially segregated state to achieve national and world prominence in the medical field.

Sam Kountz was born on October 20, 1930, in Lexa (Phillips County) to the Reverend J. S. Kountz, a Baptist minister, and his wife, Emma. He was the eldest of three sons. Kountz lived in a small town with an inadequate school system in one of the most impoverished regions of the state. He attended a one-room school in Lexa until the age of fourteen, at which point he transferred to a Baptist boarding school in the same town; he later graduated from Morris Booker College High School in Dermott (Chicot County).

Kountz applied to Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College (AM&N), now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB), in 1948, but he failed the entrance examination. Undaunted, he applied directly to Lawrence A. Davis Sr., president of Arkansas AM&N, was so impressed by Kountz’s ambition, his inquiring mind, and his determination to become a physician that he admitted him despite his scores. During Kountz’s senior year, he conducted a tour of the campus for Senator J. William Fulbright, who encouraged him in his goal of becoming a physician. Kountz earned a BS in chemistry in 1952, graduating third in his class.

After college, Kountz went to graduate school and earned an MS in biochemistry from the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville in 1956. His MD degree was conferred in 1958 from the University of Arkansas Medical Center’s School of Medicine in Little Rock (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences). He married Grace Atkin, a teacher, on June 9, 1958, one day after his graduation from medical school. They had three children. An internship at the prestigious Stanford Service, a San Francisco hospital, followed during the next two years. He completed a rigorous surgical residency there in 1965. Two significant experiences during these years shaped Kountz’s future. The first was studying with Roy Cohn, one of the world’s pioneers in organ transplantation. The second was receiving the Giannini Fellowship in surgery that supported his postdoctoral training at the San Francisco County Hospital and his postgraduate medical studies at Hammersmith Hospital in London, England, from 1962 to 1963, where he continued his surgical training.

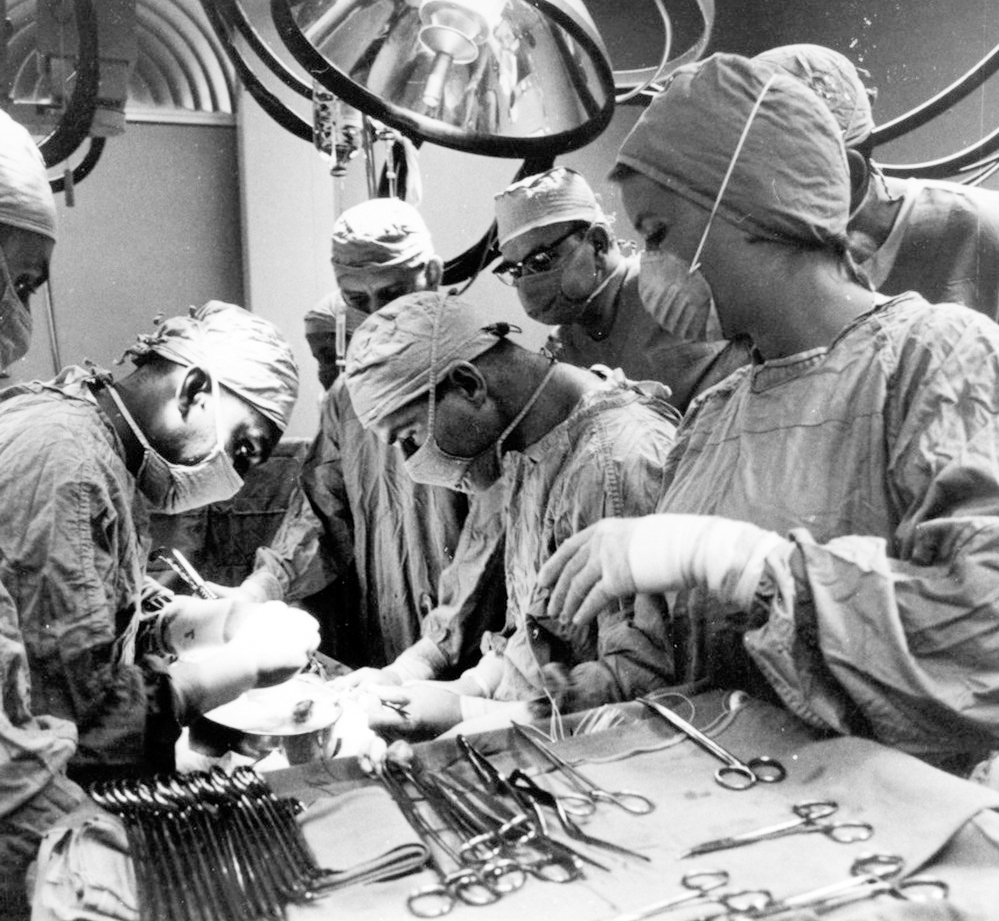

The apex of his achievement as a resident physician at Stanford was performing, in 1961, the first kidney transplant between a recipient and a donor who were not identical twins. This single achievement guaranteed his status as a pioneer in surgery. Throughout his career, he performed more than 500 kidney transplants. In 1965, he performed the first renal transplant in Egypt as a visiting Fulbright professor in the United Arab Republic.

After returning from overseas, Kountz was made assistant professor of surgery at Stanford University in 1966, becoming an associate professor in 1967. He was also director of the transplant service of the University of California at San Francisco until 1972. It was here that Kountz made the breakthrough observation that high doses of a steroid hormone, methylprednisolone, arrested the rejection of transplanted kidneys. This discovery led directly to the current drug regimens that make organ transplants using donations from unrelated donors routine. The years between 1967 and 1972 were his most productive. The above discovery and his advocacy of earlier re-implantation—that is, the implantation of a second kidney at the earliest signs of rejection—were his two greatest contributions to the field.

Kountz became professor of surgery and director of the transplant service at the University of California at San Francisco. The combination of an academic and a clinical appointment clearly showed the pathway he intended to follow. After five years there, Kountz moved to the East Coast, becoming professor of surgery and chairman of the Department of Surgery at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York. He told friends that he wanted to improve healthcare for the black community there. That same year, 1972, Kountz became chief of surgery at New York City’s Kings County Hospital Medical Center.

On a temporary teaching visit to South Africa in 1977, Kountz contracted a neurological disease that remains undisclosed to this day. Its outcome, permanent brain damage, disabled him both physically and mentally. In February 1978, he was transferred to the Burke Rehabilitation Center in White Plains, New York. Kountz remained chronically ill thereafter until he died on December 23, 1981, at home in Kings Point, New York. A memorial service was held on December 29, 1981, at the Downstate Medical Center in New York and another at the Fine Arts Building at Arkansas AM&N College on January 19, 1982. He was buried near his home in Great Neck, New York.

Kountz wrote seventy-six professional papers and other scholarly articles. The American College of Cardiology honored him in 1964 with an Outstanding Investigator Award. UA awarded him an honorary JD degree as a distinguished alumnus, honoring his pioneering achievements in the field of kidney transplant research in 1974. In 1974, Kountz was elected president of the Society of University Surgeons as an expression of respect for his clinical and research achievements. In 1976, Kountz performed a live kidney transplant on NBC’s Today show, resulting in 20,000 persons responding with offers to donate kidneys. In April 1985, the First International Symposium on Renal Failure and Transplantation in Blacks was held and dedicated to his memory. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) gives a yearly award in his honor to an outstanding black student in the sciences.

Conclusion:

The contributions to modern medicine of men such as Dr. Samuel Lee Kountz is one that Black people worldwide should be proud of. These achievements should be taught in schools and homes so that our young people will feel proud of themselves and the abilities of members of their race.

We as a people owe to ourselves and those who will come after us, to celebrate the achievements of many of our brethren. It is in celebrating them, that we will encourage this generation and younger generations to strive for excellence – to aim for Black excellence.