As the enslavement of African-Americans became a preferred aspect of the United States’ society, people began questioning the morality of bondage. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the abolition movement grew—first through the religious teachings of the Quakers and later, through anti-slavery organizations. Historian Herbert Aptheker argues that there are three major philosophies of the abolitionist movement: moral suasion; moral suasion followed by political action, and finally, resistance through physical action.

While abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison were lifelong believers in moral suasion, others such as Frederick Douglass shifted their thinking to include all three philosophies.

Many abolitionists believed in the pacifist approach to ending slavery.

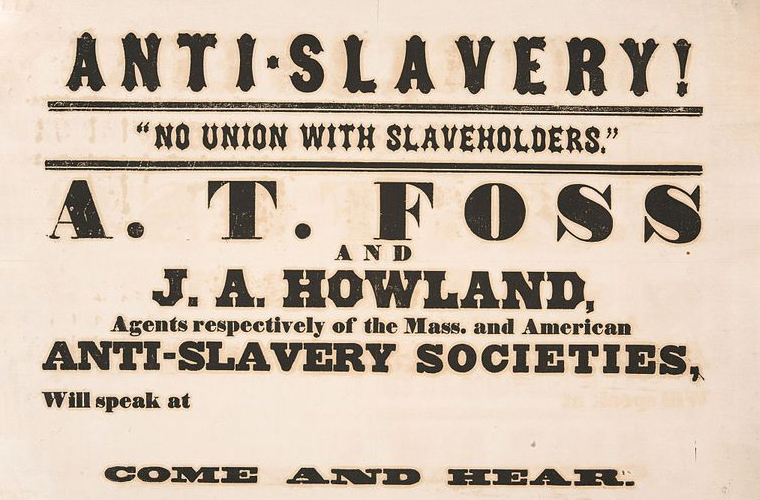

Abolitionists such as William Wells Brown and William Lloyd Garrison believed that people would be willing to change their acceptance of slavery if they could see the morality of enslaved people. To that end, abolitionists believing in moral suasion published slave narratives, such as Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and newspapers such as The North Star and The Liberator. Speakers such as Maria Stewart spoke on lecture circuits to groups throughout the North and Europe to throngs of people trying to persuade them to understand the horrors of slavery.

Towards the end of the 1830s, many abolitionists were moving away from the philosophy of moral suasion. Throughout the 1840s, local, state and national meetings of the National Negro Conventions centered around the burning question: how can African-Americans use both moral suasion and the political system to bring an end to slavery.

At the same time, the Liberty Party was building steam. The Liberty Party was established in 1839 by a group of abolitionists that believed wanted to pursue emancipation of enslaved people via the political process. Although the political party was not popular among voters, the purpose of the Liberty Party was to underscore the importance of ending enslavement in the United States.

Although African-Americans were not able to participate in the electoral process, Frederick Douglass was also a firm believer that moral suasion should be followed by political action, arguing “the complete abolition of slavery needed to rely on political forces within the Union, and the activities of abolishing slavery, therefore, should be within the Constitution.”

As a result, Douglass worked first with the Liberty and Free-Soil parties. Later, he turned his efforts to the Republican Party by writing editorials that would persuade its members to think about the emancipation of slavery.

For some abolitionists, moral suasion and political action were not enough. For those who desired immediate emancipation, resistance through physical action was the most effective form of abolition.

Harriet Tubman was one of the greatest examples of resistance through physical action. After securing her own freedom, Tubman traveled throughout southern states an estimated 19 times between 1851 and 1860.

For enslaved African-Americans, the rebellion was considered for some the only means of emancipation. Men such as Gabriel Prosser and Nat Turner planned insurrections in their attempt to find freedom. While Prosser’s Rebellion was unsuccessful, it caused southern slaveholders to create new laws to keep African-Americans enslaved. Turner’s Rebellion, on the other hand, reached some level of success–before being the rebellion ended more than fifty whites were killed in Virginia.

White abolitionist John Brown planned the Harper’s Ferry Raid in Virginia. Although Brown was not successful and he was hung, his legacy as an abolitionist who would fight for the rights of African-Americans made him revered in African-American communities.

Yet historian James Horton argues that although these insurrections were often halted, it instilled great fear in southern slaveholders. According to Horton, the John Brown Raid was “a critical moment which signals the inevitability of war, of hostility between these two sections over the institution of slavery.”