Mothers’ Milk

Slavery, Wet-Nursing, and Black and White Women in the Antebellum South

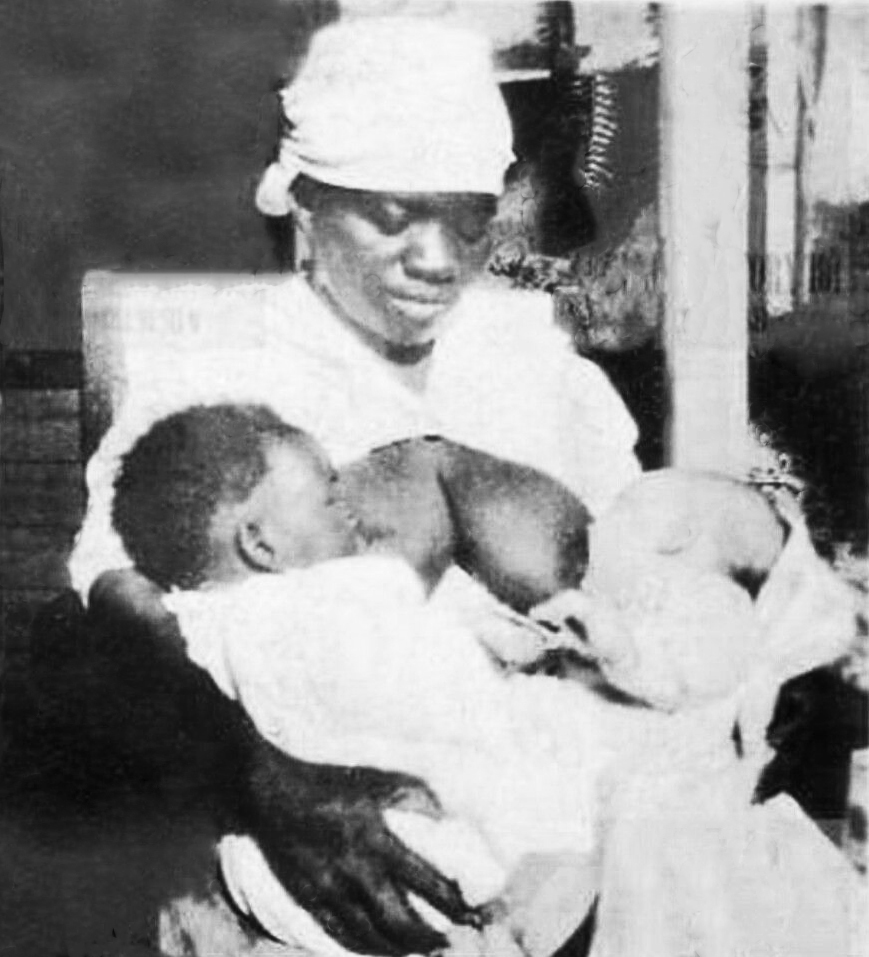

Wet nursing is a uniquely gendered kind of exploitation, and under slavery, it represented the point at which the exploitation of enslaved women as workers and as reproducers literally intersected. Feeding another woman’s child with one’s own milk constituted a form of labor, but it was work that could only be undertaken by lactating women who had borne their own children. As a form of exploitation specific to slave mothers, enforced wet nursing constituted a distinct aspect of enslaved women’s commodification. The evocative image of an enslaved wet nurse, carefully holding a white child to her breast in order to provide sustenance through her own milk, therefore holds much resonance for historians interested in gender, slavery, and relationships between black and white women in the antebellum South. Wet nursing bound women together across the racial divide, and white women also sometimes wet-nursed enslaved infants. Yet ultimately, white women used wet nursing as a tool to manipulate enslaved women’s motherhood for slaveholders’ own ends.

This article evaluates patterns of wet nursing in the antebellum South by locating the practice along a spectrum of gendered exploitation where enforced wet nursing sits at one end, women’s paid employment of “professional” wet nurses exists somewhere in the middle, and informal networks of support where women shared their breast milk lie at the other. Women in the antebellum South practiced forms of wet nursing across this spectrum. Inextricably linked with ideologies of race, ethnicity, and class, historical patterns of exploitative wet nursing have shaped contemporary distaste for the practice within the medical profession and elsewhere, even though informal networks of shared breast-feeding (for which little evidence survives) have probably been more common than has hitherto been recognized.

There have been many different forms of wet nursing in the past, involving highly complex social relations.1 By exploring the practice within broader, long-run contexts of mothers’ exploitation across time and space and under a variety of different regimes, one of which was antebellum U.S. slavery, historians can illuminate power structures that resonate with gendered, racial, and class exploitation, where a woman’s race and status impacted her ability to make choices about infant feeding. Patterns of wet nursing thus vary within different historical contexts; and while at times the practice might have involved acts of altruism by women who shared their milk, at other times, for example under antebellum slavery, wet nursing took on a more exploitative angle.

Wet nursing fostered both physical closeness and racial distance between enslaved and white women, and opportunities for resistance on the part of enslaved wet nurses remained severely limited. Conversely, slaveholding women’s relative power granted them choices about whether to use a wet nurse and occasionally (and for a variety of reasons) white women wet-nursed enslaved infants. Enslaved women, too, sometimes shared their breast milk with each other in an example of a more communal mothering process. For the most part, though, wet nursing represented a site of exploitation for enslaved women within the broader context of the antebellum slave regime. Slaveholding men and women manipulated enslaved women’s mothering through their physical labor, their reproductive abilities, and the appropriation of their breast milk.

Wet nursing is a complex and contingent process that has commonly involved women in unequal power relationships in a variety of different regimes whereby wealthier women use women from lower down the social scale as wet nurses.3 European female emigrants replicated these feeding patterns in colonial North America, using both enslaved and white-wet nurses to feed their infants. Philip Vickers Fithian, a tutor in Robert Carter’s Virginia household, wrote in his 1773 diary, “I find it is common here for people of Fortune to have their young children suckled by the Negroes!” Utilizing enslaved women as wet nurses, in the colonial era and thereafter, undoubtedly made sound economic sense for white slaveholders. Paying for the services of a wet nurse was unnecessary when one could be procured for free.