Together with interior minister Wilhelm Frick (second from the right) and propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (far right), Catholic bishops Franz Rudolf Bornewasser (Bishop of Trier) and Lugwig Sebastian (Bishop of Speyer) raise their hands in the Nazi salute at an official ceremony in Saarbrucken City Hall marking the reincorporation of the Saarland into the German Reich.

Together with interior minister Wilhelm Frick (second from the right) and propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (far right), Catholic bishops Franz Rudolf Bornewasser (Bishop of Trier) and Lugwig Sebastian (Bishop of Speyer) raise their hands in the Nazi salute at an official ceremony in Saarbrucken City Hall marking the reincorporation of the Saarland into the German Reich.

“You know what happens when atheists take over—remember Nazi Germany?” Many Christians point to Nazism, alongside Stalinism, to illustrate the perils of atheism in power. At the other extreme, some authors paint the Vatican as Hitler’s eager ally. Meanwhile, the Nazis are generally portrayed as using terror to bend a modern civilization to their agenda; yet we recognize that Hitler was initially popular. Amid these contradictions, where is the truth?

A growing body of scholarly research, some based on careful analysis of Nazi records, is clarifying this complex history. It reveals a convoluted pattern of religious and moral failure in which atheism and the nonreligious played little role, except as victims of the Nazis and their allies. In contrast, Christianity had the capacity to stop Nazism before it came to power and to reduce or moderate its practices afterward but repeatedly failed to do so because the principal churches were complicit with—indeed, in the pay of—the Nazis.

Most German Christians supported the Reich; many continued to do so in the face of mounting evidence that the dictatorship was depraved and murderously cruel. Elsewhere in Europe, the story was often the same. Only with Christianity’s forbearance and frequent cooperation could fascistic movements gain majority support in Christian nations. European fascism was the fruit of Christian culture. Millions of Christians actively supported these notorious regimes. Thousands participated in their atrocities.

What, in God’s name, were they thinking?

Before we can consider the Nazis, we need to examine the historical and cultural-religious context that would give rise to them.

Christian Foundations

Early Christian sects promoted loyalty to authoritarian rulers so long they were not intolerably anti-Christian or, worse, atheistic. Christian anti-Semitism sprang from one of the church’s first efforts to forge an accommodation with power. Reinterpreting the Gospels to shift blame for the Crucifixion from the Romans to the Jews (the “Christ killer” story) courted favor with Rome, an early example of Christian complicity for political purposes. Added energy came from Christians’ anger over most Jews’ refusal to convert.

Christian anti-Semitism was only intermittently violent, but when violence occurred it was devastating. The first outright extermination of Jews occurred in 414 c.e. It would have innumerable successors, the worst nearly genocidal in scope. At standard rates of population growth, Diaspora Jewry should now number in the hundreds of millions. That there are only an estimated 13 million Jews in the world is largely the result of Christian violence and forced conversion.

Anti-Semitic practices pioneered by Catholics included the forced wearing of yellow identification, ghettoization, confiscation of Jews’ property, and bans on intermarriage with Christians. European Protestantism bore the fierce impress of Martin Luther, whose 1543 tract On the Jews and Their Lies was a principal inspiration for Mein Kampf. In addition to his anti-Semitism, Luther was also a fervent authoritarian. Against the Robbing and Murdering Peasants, his vituperative commentary on a contemporary rebellion contributed to the deaths of perhaps 100,000 Christians and helped to lay the groundwork for an increasingly severe Germo-Christian autocracy.

With the Enlightenment, deistic and secular thinkers seeded Western culture with Greco-Roman notions of democracy and free expression. The feudal aristocracies and the churches counterattacked, couching their reactionary defense of privilege in self-consciously biblical language. This controversy would shape centuries of European history. As late as 1870, the Roman Catholic Church reaffirmed a reactionary program at the first Vatican Council. Convened by the ultraconservative Pope Pius IX (reigned 1846–1878), Vatican I stridently condemned modernism, democracy, capitalism, usury, and Marxism. Anti-Semitism was also part of the mix; well into the twentieth century, mainstream Catholic publications set an intolerant tone that later Nazi propaganda would imitate. Anti-Semitism remained conspicuous in mainstream Catholic literature even after Pope Pius XI (reigned 1922–1939) officially condemned it.

Protestantism, too, was largely hostile toward modernism and democracy during this period (with a few exceptions in northern Europe). Because Jews were seen as materialists who promoted and benefited from Enlightenment modernism, most Protestant denominations remained anti-Semitic.

With the nineteenth century came a European movement that viewed Judaism as a racial curse. Attracting both Protestant and Catholic dissidents within Germanic populations, Aryan Christianity differed from traditional Christianity in denying both that Christ was a Jew and that Christianity had grown out of Judaism. Adherents viewed Christ as a divine Aryan warrior who brought the sword to cleanse the earth of Jews. Aryans were held to be the only true humans, specially created by God through Adam and Eve; all other peoples were soulless subhumans, descended from apes or created by Satan with no hope of salvation. Most non-Aryans were considered suitable for subservient roles including slavery, but not the Jews. Spiritless yet clever and devious, Jews were seen as a satanic disease to be quarantined or eliminated.

During the same years, neopagan and occult movements gained adherents and incubated their own form of Aryanism. Unlike Aryan Christians, neopagan Aryans acknowledged that Christ was a Jew—and for that reason rejected Christianity. They believed themselves descended from demigods whose divinity had degraded through centuries of interbreeding with lesser races. The Norse gods and even the Atlantis myth sometimes decorated Aryan mythology.

Attempting to deny that Nazi anti-Semitism had a Christian component, Christian apologists exaggerate the influence of Aryan neopaganism. Actually, neopaganism never had a large following.

German Aryanism, whether Christian or pagan, became known as “Volkism.” Volkism prophesied the emergence of a great God-chosen Aryan who would lead the people (Volk) to their grand destiny through the conquest of Lebensraum (living space). A common motto was “God and Volk.” Disregarding obvious theological contradictions, growing numbers of German nationalists managed to work Aryanism into their Protestant or Catholic confessions, much as contemporary adherents of Voudoun or Santería blend the occult with their Christian beliefs. Darwinian theory sometimes entered Volkism as a belief in the divinely intended survival of the fittest peoples. Democracy had no place, but Nietzschean philosophy had some influence—a point Christian apologists make much of. Yet Nietzsche’s influence was modest, as Volkists found his skepticism toward religion unacceptable.

Though traceable to the ancient world, atheism first emerged as a major social movement in the mid-1800s. It would be associated with both pro-and antidemocratic worldviews. Strongly influenced by science, atheists tended to view all humans as descended in common from apes. There was no inherent anti-Semitic tradition. Some atheists accepted then-popular pseudoscientific racist views that the races exhibited varying levels of intellect due to differing genetic heritages. Some went further, embracing various forms of eugenics as a means of improving the human condition. But neither of these positions was uniquely or characteristically atheistic. “Scientific” racism is actually better understood as a tool by which Christians could perpetuate their own cultural prejudices—it was no accident that the races deemed inferior by Western Christian societies and “science” were the same! When we seek precursors of Nazi anti-Semitism and authoritarianism, it is among European Christians, not among the atheists, that we must search.

Following World War I, the religious situation in Europe was complex. Scientific findings of the age of the Earth, Darwin’s theory of evolution, and biblical criticism had fueled the first major expansion of nontheism at Christianity’s expense among ordinary Europeans. The churches’ support for the catastrophic Great War further fueled public disaffection, as did (in Germany) the flight of the Kaiser, in whom both Protestant and Catholic clergy had vested heavily. But religion was not everywhere in retreat: postwar Germany experienced a Christian spiritual renaissance outside the traditional churches. Religious freedom was unprecedented, but the established churches enjoyed widespread state support and controlled their own education systems. They were far more influential than today.

Roughly two-thirds of Germans were Protestant, almost all of the rest Catholic. The pagan minority claimed at most 5 percent. Explicit nontheism was limited to an intellectual elite and to committed socialists. Just 1.5 percent of Germans identified themselves as unbelievers in a 1939 census, which means either that very few Nazis and National Socialist German Worker’s Party supporters were atheists, or that atheists feared to identify themselves to the pro-theistic regime.

Most religious Germans detested the impiety, secularism, and hedonistic decadence that they associated with such modernist ideas as democracy and free speech. If they feared democracy, they were terrified by Communism, to the point of being willing to accept extreme counter-methods.

Thus it was a largely Christian, deeply racist, often anti-democratic, and in many respects dangerously primitive Western culture into which Nazism would arise. It was a theistic powder keg ready to explode.

Nazi Leaders, Theism, and Family Values

SS officers at Auschwitz in 1944. From left: Richard Baer, who became the commandant of Auschwitz in May 1944; Josef Mengele, commandant of Birkenau; Josef Kramer, hidden; and the former commandant of Auschwitz Rudolf Höss, foreground; the man on the right is unidentified.

SS officers at Auschwitz in 1944. From left: Richard Baer, who became the commandant of Auschwitz in May 1944; Josef Mengele, commandant of Birkenau; Josef Kramer, hidden; and the former commandant of Auschwitz Rudolf Höss, foreground; the man on the right is unidentified.

According to standard biographies, the principal Nazi leaders were all born, baptized, and raised Christian. Most grew up in strict, pious households where tolerance and democratic values were disparaged. Nazi leaders of Catholic backgrounds included Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, and Joseph Goebbels. Hitler did well in monastery school. He sang in the choir, found High Mass and other ceremonies intoxicating, and idolized priests. Impressed by their power, he at one time considered entering the priesthood.

Rudolf Hoess, who as commandant at Auschwitz-Birkinau pioneered the use of the Zyklon-B gas that killed half of all Holocaust victims, had strict Catholic parents. Hermann Goering had mixed Catholic-Protestant parentage, while Rudolf Hess, Martin Bormann, Albert Speer, and Adolf Eichmann had Protestant backgrounds. Not one of the top Nazi leaders was raised in a liberal or atheistic family—no doubt, the parents of any of them would have found such views scandalous. Traditionalists would never think to deprive their offspring of the faith-based moral foundations that they would need to grow into ethical adults.

So much for the Nazi leaders’ religious backgrounds. Assessing their religious views as adults is more difficult. On ancillary issues such as religion, Party doctrine was a deliberate tangle of contradictions. For Hitler consistency mattered less than having a statement at hand for any situation that might arise. History records many things that Hitler wrote or said about religion, but they too are sometimes contradictory. Many were crafted for a particular audience or moment and have limited value for illuminating Hitler’s true opinion; in any case, neither Hitler nor any other key Nazi leader was a trained theologian with carefully thought-out views.

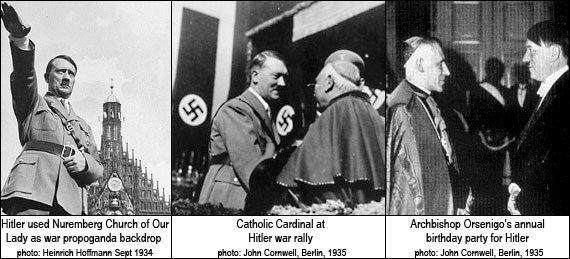

Accuracy of transcription is another concern. Hitler’s public speeches were recorded reliably but were often propagandistic. His private statements seem more likely to reflect his actual views, but their reliability varies widely. The passages Christian apologists cite most often to prove Hitler’s atheism is of questionable accuracy. Apologists often brandish them without noting historians’ reservations. Hitler’s personal library has been partly preserved, and a good deal is known about his reading habits, another possible window onto Hitler’s beliefs.[18] Also important, and often ignored by apologists, are statements made by religious figures of the time, who generally—at least for public consumption—viewed Hitler as a Christian and a Catholic in good standing. Meanwhile, the silent testimony of photographs is irrefutable, much as apologists struggle to evade this damning visual evidence. Despite these difficulties, enough is known to build a reasonable picture of what Hitler and other top Nazis believed.

Hitler was a Christian, but his Christ was no Jew. In his youth, he dabbled with occult thinking but never became a devotee. As a young man, he grew increasingly bohemian and stopped attending church. Initially no more anti-Semitic than the norm, in the years before the Great War he fell under the anti-Semitic influence of the Volkish Christian Social Party and other Aryan movements. After Germany’s stunning defeat and the ruinous terms of peace, Hitler became a full-blown Aryanist and anti-Semite. He grew obsessed with racial issues, which he unfailingly embedded in a religious context.

Apologists often suggest that Hitler did not hold a traditional belief in God because he believed that he was God. True, Hitler thought himself God’s chosen leader for the Aryan race. But he never claimed to be divine, and never presented himself in that manner to his followers. Members of the Wehrmacht swore this loyalty oath: “I swear by God this holy oath to the Führer of the German Reich and the German people, Adolf Hitler.” For Schutzstaffel (S.S.) members it was: “I pledge to you, Adolf Hitler, my obedience unto death, so help me God.”

Hitler repeatedly thanked God or Providence for his survival on the western front during the Great War, his safe escape from multiple assassination attempts, his seemingly miraculous rise from homelessness to influence and power, and his amazing international successes. He never tired of proclaiming that all of this was beyond the power of any mere mortal. Later in the war, Hitler portrayed German defeats as part of an epic test: God would reward his true chosen people with the final victory they deserved so long as they never gave up the struggle.

Reich iconography, too, reveals that Nazism never cut its ties to Christianity. The markings of Luftwaffe aircraft comprised just two swastikas—and six crosses. Likewise, the Kreigsmarine (German Navy) flag combined the symbols. Hitler participated in public prayers and religious services at which the swastika and the cross were displayed together.

Hitler openly admired Martin Luther, whom he considered a brilliant reformer. Yet he said in several private conversations that he considered himself a Catholic. He said publicly on several occasions that Christ was his savior. As late as 1944, planning the last-ditch offensive the world would know as the Battle of the Bulge, he code-named it “Operation Christrose.”

Among his Nazi cronies, Hitler criticized the established churches harshly and often. Some of these alleged statements must be treated with skepticism, but clearly, he viewed the traditional Christian faiths as weak and contaminated by Judaism. Still, there is no warrant for the claim that he became anti-Christian or antireligious after coming to power. No reliably attributed quote reveals Hitler to be an atheist or in any way sympathetic to atheism. On the contrary, he often condemned atheism, as he did Christians who collaborated with such atheistic forces as Bolshevism. He consistently denied that the state could replace faith and instructed Speer to include churches in his beloved plans for a rebuilt Berlin.

The Nazi-era constitution explicitly evoked God. Calculating that his victories over Europe and Bolshevism would make him so popular that people would be willing to abandon their traditional faiths, Hitler entertained plans to replace Protestantism and Catholicism with a reformed Christian church that would include all Aryans while removing foreign (Rome-based) influence. German Protestants had already rejected a more modest effort along these lines, as will be seen below. How Germans as a whole would have received this reform after a Nazi victory is open to question. In any case, Hitler saw himself as Christianity’s ultimate reformer, not its dedicated enemy.

Top: A German soldier in winter uniform on a motorcycle.

Top: A German soldier in winter uniform on a motorcycle.

Bottom: The inscription on the German soldier’s belt buckle translates “God With Us”.

Hitler was a complex figure, but based on the available evidence we can conclude our inquiry into his personal religious convictions by describing him as an Aryan Volkist Christian who had deep Catholic roots, strongly influenced by Protestantism, touched by strands of neopaganism and Darwinism, and minimally influenced by the occult. Though Hitler pontificated about God and religion at great length, he considered politics more important than religion as the means to achieve his agenda. None of the leaders immediately beneath Hitler was a pious traditional Christian. But there is no compelling evidence that any top Nazi was nontheistic. Any so accused denied the charge with vehemence. Reich-Führer Himmler regularly attended Catholic services until he lurched into an increasingly bizarre Aryanism.

He authorized searches for the Holy Grail and other supposedly powerful Christian and Cathar relics. A believer in reincarnation, he sent expeditions to Tibet and the American tropics in search of the original Aryans and even Atlantians. He and Heydrich modeled the S.S. after the disciplined and secretive Jesuits; it would not accept atheists as members. Goering, least ideological among top Nazis, sometimes endorsed both Protestant and Catholic traditions. On other occasions he criticized them. Goebbels turned against Catholicism in favor of a reformed Aryan faith; both his and Goering’s children were baptized. Bormann was stridently opposed to contemporary organized Christianity; he was a leader of the Church Struggle, the inconsistently applied Nazi campaign to oppose the influence of established churches.

The Nazis championed traditional family values: their ideology was conservative, bourgeois, patriarchal, and strongly antifeminist. Discipline and conformity were emphasized, marriage promoted, abortion and homosexuality despised.

Traditionalism also dominated Nazi philosophy, such as it was. Though science and technology were lauded, the overall thrust opposed the Enlightenment, modernism, intellectualism, and rationality. It is hard to imagine how a movement with that agenda could have been friendly toward atheism, and the Nazis were not. Volkism was inherently hostile toward atheism: freethinkers clashed frequently with Nazis in the late 1920s and early 1930s. On taking power, Hitler banned freethought organizations and launched an “anti-godless” movement. In a 1933 speech, he declared: “We have . . . undertaken the fight against the atheistic movement, and that not merely with a few theoretical declarations: we have stamped it out.” This forthright hostility was far more straightforward than the Nazis’ complex, often contradictory stance toward the traditional Christian faith.

Destroying Democracy: a political-religious Collaboration

As detailed by historian Ian Kershaw, Hitler made no secret of his intent to destroy democracy. Yet he came to power largely legally; in no sense was he a tyrant imposed upon the German people.

The Nazi takeover climaxed a lengthy, ironic rejection of democracy at the hands of a majority of German voters. By the early 1930s, ordinary Germans had lost patience with democracy; growing numbers hoped an authoritarian strongman would restore order and prosperity and return Germany to great-power status. Roughly two-thirds of German Christians repeatedly voted for candidates who promised to overthrow democracy. Authoritarianism was all but inevitable; at issue was merely who the new strongman would be.

What made democracy so fragile? Historian Klaus Scholder explains that Germany lacked a deep democratic tradition, and would have had difficulty in forming one because German society was so thoroughly divided into opposing Protestant and Catholic blocs. This division created a climate of competition, fear, and prejudice between the confessions, which burdened all German domestic and foreign policies with an ideological element of incalculable weight and extent. This climate erected an almost insurmountable barrier to the formation of a broad democratic center. And it favored the rise of Hitler since ultimately both churches courted his favor—each fearing that the other would complete the Reformation or the Counter-Reformation through Hitler.

Carefully plotting his strategy, Hitler purged some of the Volkish Nazi radicals most belligerent toward the traditional Christian churches. In this way, he lessened the risk of ecclesiastical opposition. At the same time, he knew that the presence of both Catholics and Protestants among the Nazi leadership would ease churchmen’s fears that the Party might engage in sectarianism.

Though it had many Catholic leaders (including Hitler), the Nazi Party relied heavily on Protestant support. Protestants had given the Party its principal backing during the years leading up to 1933 at a level disproportionate to their national majority. Evangelical youth was especially pro-Nazi. It has been estimated that as many as 90 percent of Protestant university theologians supported the Party. Indeed, the participation of so many respected Protestants gave an early, comforting air of legitimacy to the often-thuggish Party. So did the frequent sight of Sturmabteilung (S.A.) units marching in uniform to church.

As German life between the wars grew more desperate, some Protestant pastors explicitly defended Nazi murders of “traitors to the Volk” from the pulpit. Antifascist Protestants found themselves marginalized. The once-unlikely topic of Volkist-Protestant compatibility became the leading theological subject of the day. This is less surprising when we consider that Volkism and German Protestantism were both strongly nationalistic; Lutheranism, in particular, had German roots.

This mirage of harmony enticed Hitler into a naïve attempt to unite the German Protestant churches into a single Volkish body under Nazi control. Launched shortly after the Nazis came to power, this project failed immediately. The evangelical sects proved as unwilling as ever to get along with one another, though much of their clergy eventually Nazified.

Catholicism and the Nazi Takeover

Ironically—but, as we shall see, for obvious reasons—Chancellor Hitler had greater initial success reaching an accommodation with Roman Catholic leaders than with the Protestants. The irony lay in the fact that the Catholic Zentrum (Center) Party had been principally responsible for denying majorities to the Nazis in early elections. Although Teutonic in outlook, German Catholics had close emotional ties to Rome. As a group, they were somewhat less nationalistic than most Protestants. Catholics were correspondingly more likely than Protestants to view Hitler (incorrectly) as godless, or as a neo-heathen anti-Christian. Catholic clergy consistently denounced Nazism, though they often undercut themselves by preaching traditional anti-Semitism at the same time.

Even so, and despite Catholicism’s minority status, it would be German Catholics and the Roman Catholic Church whose actions would at last put total power within the Nazis’ reach.

Though it was not without antimodernists, the Catholic Zentrum party had antagonized the Vatican during the 1920s by forming governing coalitions with the secularized, moderate Left-oriented Social Democrats. This changed in 1928 when the priest Ludwig Kaas became the first cleric to head the party. To the dismay of some Catholics, Kaas and other Catholic politicians participated both actively and passively in destroying democratic rule, and in particular the Zentrum.

The devoutly Catholic chancellor Franz von Papen, not a fascist but stoutly right-wing, engineered the key electoral victory that brought Hitler to power. Disastrously Papen dissolved the Reichstag in 1932, then formed a Zentrum-Nazi coalition in violation of all previous principles. It was Papen who in 1933 made Hitler chancellor, Papen stepping down to the vice chancellorship.

The common claim that Papen acted in the hope that the Nazis could be controlled and ultimately discredited may be true, partly true, or false; but without Papen’s reckless aid, Hitler would not have become Germany’s leader.

The church congratulated Hitler on his assumption of power. German bishops released a statement that wiped out past criticism of Nazism by proclaiming the new regime acceptable, then followed doctrine by ordering the laity to be loyal to this regime just as they had commanded loyalty to previous regimes. Since Catholics had been instrumental in bringing Hitler to power and served in his cabinet, the bishops had little choice but to collaborate.

German Catholics were stunned by the magnitude and suddenness of this realignment. The rigidly conformist church had flipped from ordering its flock to oppose the Nazis to commanding cooperation. A minority among German Catholics was appalled and disheartened. But most “received the statement with relief—indeed with rejoicing—because it finally also cleared the way into the Third Reich for Catholic Christians” alongside millions of Protestants, who joined in exulting that the dream of a Nazi-Catholic-Protestant nationalist alliance had been achieved. The Catholic vote for the Nazis increased in the last multi-party elections after Hitler assumed control, doubling in some areas, inspiring a mass Catholic exodus from the Zentrum to the fascists. After the Reichstag fire, the Zentrum voted en masse to support the infamous Enabling Act, which would give the Hitler-Papen cabinet executive and legislative authority independent of the German Parliament. Zentrum’s bloc vote cemented the two-thirds majority needed to pass the Act.

Why did the church direct its party to provide the critical swing vote? It had its agenda, as we shall see below.

Deal Making with the Devil

Even after the Enabling Act, Hitler’s position remained tenuous. The Nazis needed to deepen majority popular support and cement relations with a skeptical German military. Hitler needed to ally all Aryans under the swastika while he undermined and demoralized regime opponents. What would solidify Hitler’s position? A foreign policy coup: the Concordat of 1933 between Nazi Germany and the Vatican.

Above, Cardinal Secretary of State, Eugenio Pacelli (later to become Pope Pius XII) signs the Concordat between Nazi Germany and the Vatican at a formal ceremony in Rome on 20 July 1933. Nazi Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen sits at the left, Pacelli in the middle, and the Rudolf Buttmann sits at the right.

Above, Cardinal Secretary of State, Eugenio Pacelli (later to become Pope Pius XII) signs the Concordat between Nazi Germany and the Vatican at a formal ceremony in Rome on 20 July 1933. Nazi Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen sits at the left, Pacelli in the middle, and the Rudolf Buttmann sits at the right.

The national and international legitimacy Hitler would gain through this treaty was incalculable. Failure to secure it after intense and openly promoted effort could have been a crushing humiliation. Hitler put exceptional effort into the project. He courted the Holy See, emphasizing his own Christianity, simultaneously striving to intimidate the Vatican with demonstrations of his swelling power.

Catholic apologists describe the Concordat of 1933 as a necessary move by a church desperate to protect itself against a violent regime that forced the accord upon it—passing over the contradiction at the heart of this argument. Actually, having failed in repeated attempts to negotiate the ardently desired concordat with a skeptical Weimar democracy, Kaas, Papen, the future Pius XII (who reigned 1939–1958), the sitting Pius XI, and other leading Catholics saw their chance to get what they had been seeking from an agreeable member of the church—that is, Hitler—at a historical moment when he and fascism, in general, were regarded as a natural ally by many Catholic leaders. Negotiations were initiated by both sides, modeled on the mutually advantageous 1929 concordat between Mussolini and the Vatican.

Now Zentrum’s pivotal role in assuring passage of the Enabling Act can be seen in context. It was part of the tacit Nazi-Vatican deal for a future concordat. The Enabling Act vote hollowed Zentrum, leaving little more than a shell. Thus, a clergy far more interested in church power than democratic politics could take control of both sides of the negotiating table. In a flagrant conflict of interest, the devout Papen helped to represent the German state. Concordat negotiations were largely held in Rome so that Kaas could leave his vanishing party yet more rudderless. Papen, Kaas, and the future Pius XII worked overtime to finalize a treaty that would, among other things, put an end to the Zentrum. In negotiating away the party he led, Kaas, eliminated the last political entity that might have opposed the new Führer. Nor did the Vatican protect Germany’s Catholic party. Contrary to the contention of some, evidence indicates that the Vatican was pleased to negotiate away all traces of the Zentrum, for which it had no more use save as a bargaining chip. In this, the Holy See treated Zentrum no differently than it had the Italian Catholic party, which it negotiated away in the Concordat with Mussolini.

Hitler sought to eliminate Catholic opposition in favor of obligatory loyalty to his regime. For its part, the church was obsessed with its educational privileges, and especially with securing fresh sources of income. It would willingly sacrifice political power to protect them. As both sides worked in haste to produce a treaty that would normally have required years to complete, Hitler took masterful advantage of the Vatican over-eagerness. Filled with “certainty that Rome neither could nor would turn back, [Hitler] was now able to steer the negotiations almost as he wanted. The records prove he exploited the situation to the full.”[32] Indeed, Hitler was so confident that he had the Church in his lap that he went ahead and promulgated his notorious sterilization decree before the Concordat’s final signing. Hitler’s project for involuntary sterilization of minorities and the mentally ill was a direct affront to Catholic teaching.