Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School, one of the oldest Roman Catholic girls’ schools in the nation, has long celebrated the vision and generosity of its founders: a determined band of Catholic nuns who championed free education for the poor in the early 1800s.

The sisters, who established an elite academy in Washington, D.C., also ran “a Saturday school, free to any young girl who wished to learn — including slaves, at a time when public schools were almost nonexistent and teaching slaves to read was illegal,” according to an official history posted for several years on the school’s website.

But when a newly hired school archivist and historian started digging in the convent’s records a few years ago, she found no evidence that the nuns had taught enslaved children to read or write. Instead, she found records that documented a darker side of the order’s history.

Detail of an 1846 James Alexander Simpson painting of Georgetown Visitation Convent in Washington. A few years ago, an archivist discovered a darker side of the order’s official school history.

Detail of an 1846 James Alexander Simpson painting of Georgetown Visitation Convent in Washington. A few years ago, an archivist discovered a darker side of the order’s official school history.

“Nothing else to do than to dispose of the family of Negroes,” Mother Agnes Brent, the convent’s superior, wrote in 1821 as she approved the sale of a couple and their two young children. The enslaved woman was just days away from giving birth to her third child.

Are nuns disposing of black families? I have been poring over 19th-century church records for several years now and such casual cruelty from leaders of the faith still takes my breath away. I am a black journalist and a black Catholic. Yet I grew up knowing nothing about the nuns who bought and sold human beings.

For generations, enslaved people have been largely left out of the origin story traditionally told about the Catholic Church. My reporting on Georgetown University, which profited from the sale of more than 200 slaves, has helped to draw attention in recent years to universities and their ties to slavery. But slavery also helped to fuel the growth of many contemporary institutions, including some churches and religious organizations.

Historians say that nearly all of the orders of Catholic sisters established by the late 1820s owned slaves. Today, many Catholic sisters are outspoken champions of social justice and some are grappling with this painful history even as lawmakers in Congress and presidential candidates debate whether reparations should be paid to the descendants of enslaved people.

Their approaches vary in scope and some sisters have expressed misgivings, fearful that exposing the past may leave them open to criticism. But as they search their archives and reflect on the way forward, some religious women are developing frameworks that may serve as road maps for other institutions striving to acknowledge and atone for their participation in America’s system of human bondage.

The Georgetown Visitation sisters and school officials have organized a series of discussions for students, faculty, staff, and alumnae, including a prayer service in April that commemorated the enslaved people “whose involuntary sacrifices supported the growth of this school.” They have published an online report about the convent’s slaveholding — an article by the school’s archivist and historian also appeared in The U.S. Catholic Historian this spring — and have digitized their records related to slavery, making them available to the public for the first time.

A monument to enslaved people at the cemetery near the Society of the Sacred Heart in Grand Coteau, La.

A monument to enslaved people at the cemetery near the Society of the Sacred Heart in Grand Coteau, La.

The Religious of the Sacred Heart, who owned about 150 enslaved people in Louisiana and Missouri, tracked down dozens of descendants of the people they once owned and invited them to a memorial ceremony in Grand Coteau, La. At the ceremony last fall, the nuns unveiled a monument to the slaves in the local parish cemetery and a plaque on an old slave’s quarters. They also announced the creation of a scholarship fund for African-American students at their Catholic school, which was built, in part, by enslaved laborers.

“It wasn’t just a question of looking at the past,” Sister Carolyn Osiek, the provincial archivist for the Society of the Sacred Heart United States/Canada, said. “It was: ‘What do we do with this now?’”

Sister Osiek, who led the Society of the Sacred Heart’s committee on slavery and reconciliation, said her order wanted the descendants to know that their ancestors had played a vital role in developing and sustaining the convent and school. (The Religious of the Sacred Heart are members of the Society of the Sacred Heart.)

“We couldn’t have done it without you,” she said, describing the message delivered to the descendants by the order’s provincial leader. “For so long we haven’t acknowledged you, and we’re sorry about that.”

But the soul-searching has not been universally embraced. Some descendants declined to participate in the ceremony in Louisiana, finding it too painful. And some nuns have expressed unease about the decision to unearth the past.

Sister Margaret Caire, a member of the Society of the Sacred Heart, and Jonty Coco, a descendant of one of the families owned by the sisters, outside the former slave quarters in Grand Coteau, La.

Sister Margaret Caire, a member of the Society of the Sacred Heart, and Jonty Coco, a descendant of one of the families owned by the sisters, outside the former slave quarters in Grand Coteau, La.

“A lot of communities now are very committed to dealing with issues of racism, but the fact is their own history is problematic,” said Margaret Susan Thompson, a historian at Syracuse University who has examined Catholic nuns and race in the United States.

“They’re beginning to confront their own racism, and their own complicity in the racism of the past,’’ she said, “but it’s a very long road.”

Sister Irma L. Dillard, an African-American member of the Religious of the Sacred Heart, said that some white nuns felt reluctant to revisit this history because they feared “being seen as racist and bad.” She praised the steps taken by her order so far and said she hopes more will be done.

She said that only one scholarship has been given so far, a gesture that she described as “a token.”

And while she would like to see the order’s history of slaveholding incorporated into the curriculum of the schools they founded, few of those schools have publicly acknowledged their origins, she said, despite the extensive research that has been done.

“Not one of the school websites has anything about enslavement,” said Sister Dillard, who was also a member of the society’s committee on slavery, accountability, and reconciliation. “We’ve whitewashed our history.”

At Georgetown Visitation, Susan Nalezyty, the school archivist and historian, discovered that the order’s ties to slavery were much deeper than had been previously publicized. None of the official histories described the extent of the sisters’ slaveholding or detailed the nuns’ profits from the sale of humans.

Sister Mary Berchmans, mother superior of the Georgetown Visitation Monastery and president emerita of the school, inside a classroom at the Georgetown Visitation school in Washington.

Sister Mary Berchmans, mother superior of the Georgetown Visitation Monastery and president emerita of the school, inside a classroom at the Georgetown Visitation school in Washington.

And for more than a decade, the school’s website hailed the Georgetown Visitation nuns for their “generosity of spirit” for teaching slaves to read, an anecdote that was passed down through oral tradition, school officials said. That language, which remains unsubstantiated, was removed from the website in 2017.

“The committee is happy, the school is happy to now have information so that we can speak on this history with authority based on what the documentary evidence tells us,” Dr. Nalezyty said.

It is history that has largely faded from our public consciousness, even among many of the three million black Catholics who account for about 3 percent of Catholics in the United States.

Growing up in New York City, I lived just blocks from a convent that ran a bookstore and a community festival that became a highlight of my childhood summers. Catholic nuns educated my mother, my aunts, three of my uncles, and both of my sisters. My mother and her family, who emigrated from the Bahamas to Staten Island, even lived for a time on a farm run by Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker movement and a candidate for sainthood. The church we knew tended to Irish and Italian immigrants, their children and grandchildren, and a smattering of black families. We never imagined that any of its religious orders had ties to slavery.

Darren W. Davis, a political scientist at the University of Notre Dame and a co-author of “Perseverance in the Parish?” about black Catholics, said that people often assume that most black Catholics are recent converts. But many belong to families that have passed down the faith from one generation to the next.

Some embraced the faith after landing in cities like Chicago and New York during the Great Migration that carried millions of African-Americans north, he said. Others have deeper roots. “Catholicism goes back centuries, especially in families from the South,” he said.

In the early decades of the American republic, the Catholic Church established its primary foothold in the South, in communities where slaveholding was considered a mark of wealth and prestige for parishioners, clergy, and nuns. It was not unusual for American-born priests and nuns to grow up in slave-holding families, and many orders relied on slave labor, historians say.

The Jesuit priests, who founded and ran Georgetown, for instance, were among the largest slaveholders in Maryland. And as women began to enter the first Catholic convents in the late-18th and early-19th centuries, some brought their human property with them as part of their dowries, historians say. (I stumbled across this history during my reporting on Georgetown.)

Wealthy supporters and relatives of the nuns also donated enslaved people to the convents. Meanwhile, Catholic sisters bought, sold, and bartered enslaved people. Some nuns accepted slaves as payment for tuition to their schools or handed over their human property as payment for debts, records show.

Mary Ewens, the author of “The Role of the Nun in Nineteenth-Century America,’’ found that seven of the eight first orders of Catholic nuns established in the United States owned slaves by the 1820s. In a more recent study, Joseph G. Mannard revealed that an eighth order did as well, at least for a time.

“They really came to define Catholicism in the United States,” Dr. Thompson said of these early Catholic nuns. “Between 1810 and 1820, sisters came to outnumber priests in the United States. They set the foundational patterns for what sisters did in the U.S.”

Some nuns expressed distaste for slavery while others described their reluctance to sell the people they owned, and records document some efforts to keep families together.

Sisters from both Georgetown Visitation and Sacred Heart united families in which the husband was owned by the nuns and the wife was owned by someone else. In each case, the sisters purchased the wives to bring the family together. (The Georgetown Visitation nuns bought the family’s children as well.) The Carmelites of Baltimore cared for some elderly slaves when they grew infirm. The Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Kentucky remained so connected to their former slaves that scores returned, with children and grandchildren, to celebrate the convent’s centennial in 1912.

People formerly enslaved by the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth returned with their families to celebrate the religious order’s centennial in 1912.

People formerly enslaved by the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth returned with their families to celebrate the religious order’s centennial in 1912.

But Dr. Mannard, a historian at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania, and other researchers have found that the nuns’ financial needs — and the appeal of unpaid labor — often trumped any reluctance to traffic in humans.

“In spite of my repugnance for having Negro slaves, we may be obliged to purchase some,” Rose Philippine Duchesne, who established the Society of the Sacred Heart in the United States, wrote in 1822. A year later, the Sacred Heart sisters in Grand Coteau purchased their first-person, an enslaved man named Frank Hawkins, for $550.

In 1830, the Carmelite sisters cited concerns about having to undertake “the disposal of our poor servants” to help explain their reluctance to move to Baltimore from their plantation in rural Maryland. But they dropped those objections after learning that the sale would help pay off their debts and allow them to keep their rural estate. They sold at least 30 people, Dr. Mannard said.

Nearly a decade later, the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s in Emmitsburg, Md., founded by Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first native-born American to be canonized as a saint, agreed to follow the counsel of their religious superior who told them they could sell their “yellow boys” at 10 to 12 percent profit “without doing an injustice to anyone.”

As for the Georgetown Visitation nuns, the profits from slave sales would become a vital lifeline during a period of expansion. In the 1820s, the sisters embarked on a building campaign, which left them saddled with debt. To ease the financial strain, they sold at least 21 people between 1819 and 1822, the records show. When some buyers dawdled in making payments, the sisters took them to court, Dr. Nalezyty found.

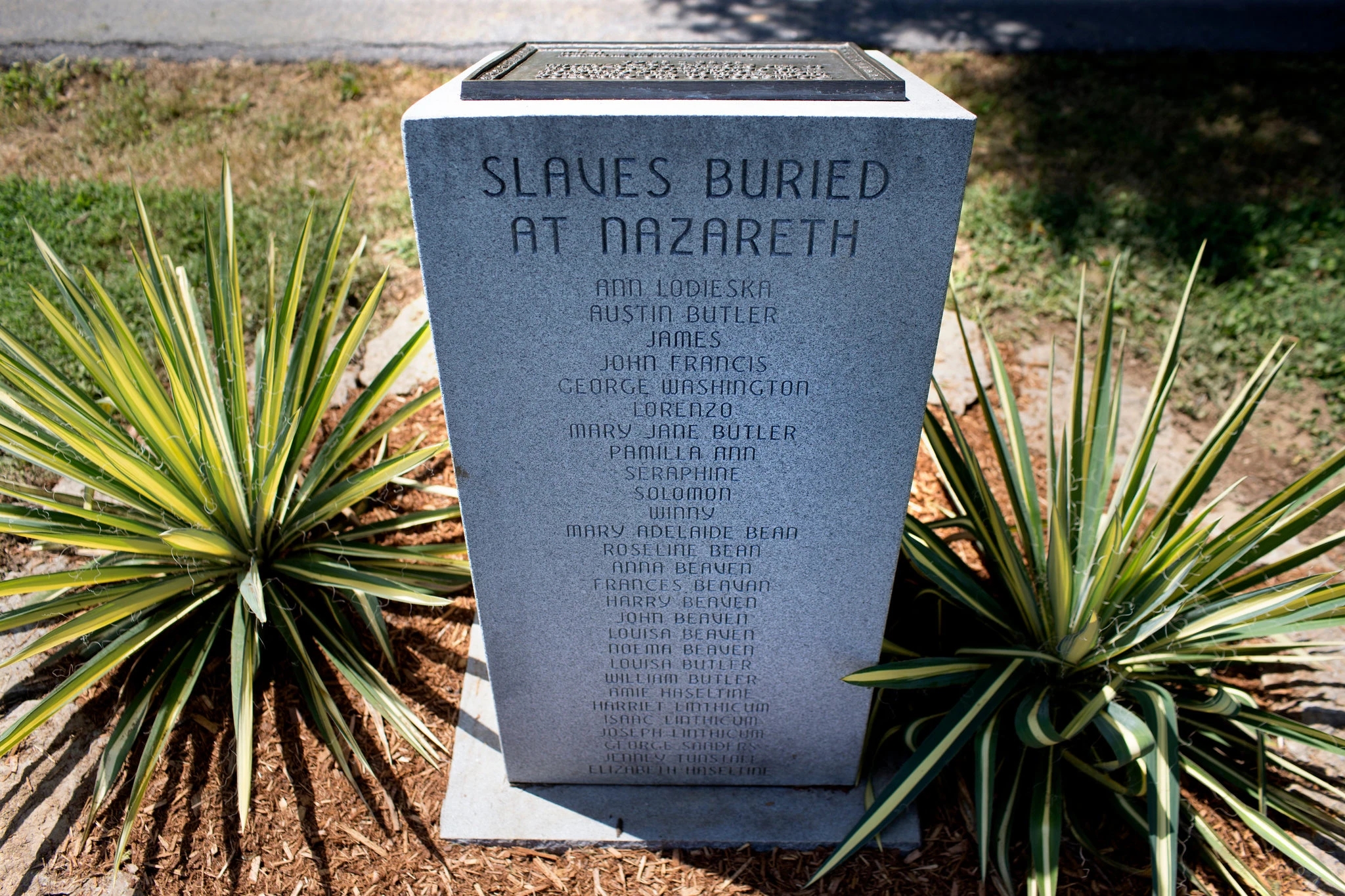

A monument for the enslaved was erected in 2012 at the cemetery of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Nazareth, Ky.

A monument for the enslaved was erected in 2012 at the cemetery of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Nazareth, Ky.

The Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Kentucky, who owned 30 people at Emancipation, were among the first sisters to seek to make amends. They joined with two other orders — the Dominicans of Saint Catharine and the Sisters of Loretto — to host a prayer service in 2000 where they formally apologized for their slaveholding. In 2012, the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth erected a monument at a cemetery where many of the enslaved people were buried. So far, they have identified three descendants of the people they once owned.

“Their contributions had been ignored,” said Sister Theresa Knabel, who researched the order’s history and reached out to descendants. “We needed to know who they were, know their names, know their story, and make them visible.”

Roslyn Chenier, an African-American software consultant in Atlanta, learned that her forbears had been owned by the Religious of the Sacred Heart when she was contacted by Sister Maureen J. Chicoine, who has researched the history of the order and has identified dozens of descendants.

“I was amazed, amazed,” said Ms. Chenier, who attended the ceremony organized by the sisters in Grand Coteau last September. “It was very emotional.”

Ms. Chenier gave up practicing many years ago. But some of her relatives remain devout. Learning that their ancestors were owned by nuns astonished them. But it hasn’t shaken their faith, she said. It hasn’t shaken her strong Catholic identity, either.

That doesn’t surprise Father Gregory C. Chisholm, a black priest who heads St. Charles Borromeo, Resurrection, and All Saints parish in Harlem. He has had a number of conversations about Catholic slaveholding. The conversations are often painful, he said, but few black people are surprised to hear about racism among the clergy.

Older people still remember the days of segregated pews and segregated churches, he said. Others have encountered racism within their own parishes and within their own religious orders, even as they cherish the blessings that Catholicism brings to their lives.

Sister Theresa Knabel, right, and Sister Adeline Fehribach at the monument for the enslaved at the cemetery of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Nazareth, Ky.

Sister Theresa Knabel, right, and Sister Adeline Fehribach at the monument for the enslaved at the cemetery of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Nazareth, Ky.

“This whole thing reveals the ways in which the religion has failed us in some way,” said Father Chisholm, who says he is encouraged by the church’s recent efforts to acknowledge its past. “It’s hard. It’s difficult. But it’s good. It’s a way for our church to be renewed and that’s what it has to be. It has to be renewed.’’

In November, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops addressed slavery in a pastoral letter that discussed racism within the church and asked for forgiveness. In 2017, Father Timothy P. Kesicki, president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, apologized for the 1838 sale of enslaved people that helped keep Georgetown University afloat.

The sisters say they still have work to do. At Georgetown Visitation, a committee is focusing on embedding the history more deeply into the school curriculum. The Sisters of Charity of Nazareth are creating a permanent exhibit on their campus that will highlight the contributions of African-Americans to their congregation. The Religious of the Sacred Heart are weighing additional steps to promote inclusion and diversity and to eradicate racism within their order and in the schools they sponsor.

Sister Dillard and other members of her committee have already visited some of the schools founded by their order, sharing the history that their sisters have unearthed and urging young people to commit themselves to combat systemic racism.

She wants to make sure that students no longer grow up, as I did, without learning about the enslaved people who helped to build the church. She wants to make sure that we all know their names.