By the time he made it to a Union encampment in Baton Rouge in March 1863, Peter had been through hell. Bloodhounds had chased him. He had been pursued miles, had run barefoot through creeks and across fields. He had survived, if barely. When he reached the soldiers, Peter’s clothing was ragged and soaked with mud and sweat.

But his ten-day ordeal was nothing compared to what he had already been through. During Peter’s enslavement on John and Bridget Lyons’ Louisiana plantation, Peter endured not just the indignity of slavery, but a brutal whipping that nearly took his life. And when he joined the Union Army after his escape from slavery, Peter exposed his scars during a medical examination.

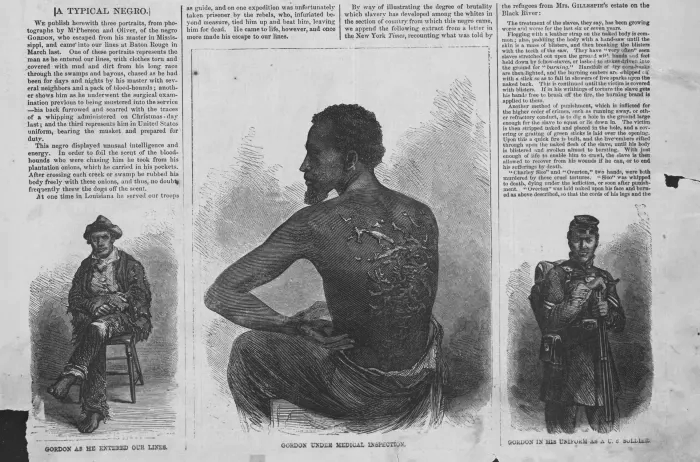

Raised welts and strafe marks crisscrossed his back. The marks extended from his buttocks to his shoulders, calling to mind the viciousness and power with which he had been beaten. It was a hideous constellation of scars: visual proof of the brutality of slavery. And for thousands of white people, it was a shocking image that helped fuel the fires of abolition during the Civil War.

A photograph of Peter’s back became one of the most widely circulated images of slavery of its time, galvanizing public opinion and serving as a wordless indictment of the institution of slavery. Peter’s disfigured back helped bring the stakes of the Civil War to life, contradicting Southerners’ insistence that their slaveholding was a matter of economic survival, not racism. And it showed just how important mass media was during the war that nearly destroyed the United States.

Not much is known about Peter aside from the testimony he gave the medical examiners at the camp and the image of his back and the keloid scars he suffered from his beating. He told examiners that he had left the plantation ten days ago and that the man who whipped him was the plantation’s overseer, Artayou Carrier. After the whipping, he was told he had become “sort of crazy” and had threatened his wife. As he lay in bed recovering, the plantation owner fired the overseer. But Peter had already determined to escape.

Peter and three other enslaved people escaped by the cover of night, but one of their companions were murdered by slave hunters who came in pursuit of Lyons’ property. The surviving escapees rubbed onions on their bodies to escape the bloodhounds the slave catchers used to pursue them. Only after days of pursuit did they reach the Union encampment, weeping with joy when they were greeted by black men in uniform. They immediately enlisted.

The white soldiers who inspected Peter were horrified by his wounds. “Suiting the action to the word, he pulled down the pile of dirty rags that half concealed his back,” said a witness. “It sent a thrill of horror to every white person present, but the few Blacks who were waiting…paid but little attention to the sad spectacle, such terrible scenes being painfully familiar to them all.”

But though Peter’s experience was shared by thousands of enslaved people, it was foreign to many Northerners who had never witnessed slavery and its brutality with their own eyes. Mass media was still relatively new, and though escaped slaves and other eyewitnesses brought stories of whippings and other punishments north, few had seen the evidence of the oppression of slaves.

McPherson and Oliver, two itinerant photographers who were at the camp, photographed Peter’s back, and the photo was reproduced and distributed as a carte-de-visite, a trendy new photographic format. The small cards were cheap to produce and became wildly popular during the Civil War, providing a near-instant look at the war, and its players, as it unfolded.

Peter’s photo quickly spread across the nation. “I have found a large number of the four hundred or so contrabands [people who had escaped slavery and were now protected by the Union Army] examined by me to be as badly lacerated as the specimen represented in the enclosed photograph,” J.W. Mercer, a Union Army surgeon in Louisiana, wrote on the back of the card. He sent it to Colonel L.B. Marsh.

“This Card Photograph should be multiplied by 100,000, and scattered over the States,” an anonymous journalist wrote. The image was a powerful rebuttal to the lie that enslaved people were treated humanely, a common refrain of those who didn’t think slavery should be abolished.

Three illustrations showing Peter after his escape, the welts from being whipped upon his back, and in uniform after he had joined the Union Army, featured in McPherson and Oliver in July 1863.

Three illustrations showing Peter after his escape, the welts from being whipped upon his back, and in uniform after he had joined the Union Army, featured in McPherson and Oliver in July 1863.

Peter was not the only runaway slave whose image helped stoke anti-slavery sentiments. As soon as the carte de visite was introduced in 1854, the technology became popular in abolitionist circles. Others who had escaped from slavery, like Frederick Douglass, posed for popular portraits. Sojourner Truth even used the proceeds from the cartes de visites she sold at her speeches to fund speaking tours and help recruit black soldiers.

But Peter’s strafed back was perhaps the most visible—and significant—photograph of a former slave. It was sold by abolitionists who used it to raise money for their cause, and gained the name “The Scourged Back” or “Whipped Peter.” When it was published in Harper’s Weekly, the most popular periodical of its day, it reached a massive audience. The spread also stoked confusion when Peter’s name was listed instead as “Gordon.”

The photo was also decried as fake by the Copperheads, a nickname for a faction of Northerners who opposed the war and was loudly sympathetic of the South and of slave ownership. An unnamed Union Army soldier who had taken the photographs shot back with a long account that upheld the veracity of the photograph. “All the logic of the blind and infatuated believers in Human Slavery cannot arrest or thwart the progress of truth, any more than they can prevent the development of the positive picture when aided by the silent and powerful process of chemical action,” he wrote.

Though Peter’s body was used as proof of the cruelty of slavery, accounts of his ordeal are saturated with the racism that pervaded American society, even among sympathetic white Northerners. The Harper’s spread referred to Peter as possessing “unusual intelligence and energy,” laying bare stereotypes of black people as stupid and lazy. A surgeon who was present at his examination noted that “nothing in his appearance indicates any unusual viciousness,” as if anything could justify a whipping.

Despite the racism of the day, though, Peter’s portrait did galvanize even those who had never spoken out against slavery. “What began as a very local — even private — image ultimately achieved something much grander because it circulated so widely,” historian Bruce Laurie told the Boston Globe.

It’s unclear what Peter did during the rest of the war, or what his life was like after the Civil War came to an end. Though slavery had been abolished, he—and the others who had been subjugated, beaten, and demeaned during hundreds of years of slavery in the Americas—still bore the scars of enslavement.

As historian Michael Dickman notes, whipping was a common punishment on Southern plantations, though there was a debate about whether to use it sparingly to keep slaves from revolting. “Masters desired to maintain order in a society in which they were in unquestionable positions of authority,” he writes. “They used the whip as a tool to enforce this vision of society. Slaves, on the other hand, through their victimization and punishment, viewed the whip as the physical manifestation of their oppression under slavery.”

For white Southerners and enslaved black people, the sight of a back like Peter’s was chillingly commonplace. For white Northerners, though, Peter’s scourged body made slavery’s brutality impossible to deny. It remains one of the era’s best-known—and most appalling—images.