The Slocum Massacre occurred on July 29, 1910, in Slocum, Texas, an unincorporated community in southeast Anderson County. The city used to be home to a thriving African American community with several businesses and farms owned by black residents.

Leading up to the massacre, the lynching of a black man in nearby Cherokee County sparked racial tensions in the Slocum area. While rumors circulated that black residents had been meeting in Slocum to plan an armed rebellion. Racial tensions only intensified when a white man reportedly sought to collect a disputed debt from a well-respected black farmer named Abe Wilson and when a road construction foreman put an African American in charge of soliciting aid for road improvements. A confrontation erupted, enraging Jim Spurger, a local white farmer, who became the primary agitator of the conflict that led to the massacre. Many newspapers and eyewitness accounts reported that Spurger instigated the events by claiming that blacks had threatened him.

Driven by Spurger and other white vigilantes, an angry mob of heavily armed white men from all over Anderson County roamed throughout Slocum in groups. According to some reports, two hundred men laid siege to the city. They fired guns on black residents at will. African Americans fled as word spread from survivors of the carnage. White mobs trailed fleeing blacks into the surrounding forests and marshes and shot them in the back. Every initial newspaper portrayed African Americans as “armed instigators,” which were gross mischaracterizations.

Newspapers reported that the estimated death toll of black residents was 8 to 22 victims. Black community members provided a contrasted this report by stating that there was a minimum of 40 who had died and that it may have reached upwards of 200 victims. Anderson County Sheriff William H. Black stated, at the time, that it was challenging to obtain the death toll because black bodies had been scattered all over the woods. Many black residents fled the town during and after the massacre, leaving behind real estate property and other assets to save their lives. White residents later seized their property. For instance, Jack Hollie, a formerly enslaved man, lost his dairy, granary, general store, and 700 acres of land to white residents after he and his family fled the city.

Almost all of Slocum’s residents were subpoenaed to testify, and white men who refused were arrested. Spurger and at least fifteen other white men were arrested for the attacks. In addition, Spurger and six of the men were indicted on 22 counts of murder. However, they were never tried. The indictments received little attention when Judge Benjamin Howard Gardner moved the trial to Harris County, where the charges were eventually dropped. None of the attackers were ever prosecuted.

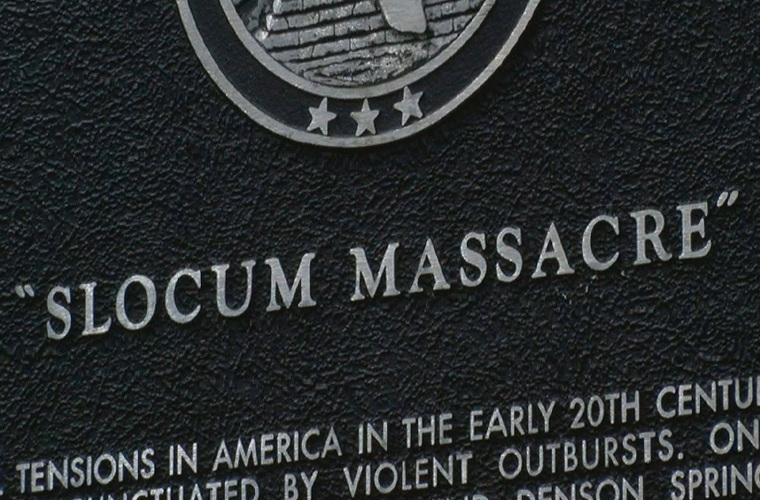

Today, the city of Slocum reflects the relic of its history. While most nearby towns have black populations of more than 20 percent, Slocum is just below seven percent. Due to the efforts led by Constance Hollie-Jawaid, a descendant of the victims, a historical marker was dedicated to commemorating the event in 2016.