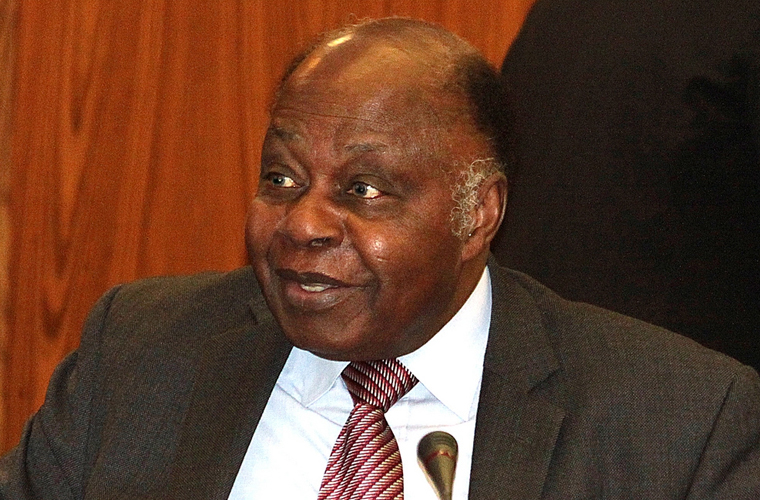

Ghanaian-born materials scientist Thomas Mensah has had a high-flying career, first as a scientist and then as an entrepreneur. Mensah has at least 14 patents to his name, has edited two books and authored several articles, and has been involved with several of the fastest-growing fields in engineering, notably fiber optics and superconductor technology. Late in his career, Mensah attempted to turn his theoretical knowledge into moneymaking enterprises, but his efforts ran up against some of the obstacles that face scholars who plunge into the hard world of finance facts and figures. He has an impressive record of accomplishment as one of the few blacks, and even fewer Africans, to excel at the highest levels of science.

Thomas O. Mensah was born in Kumasi, Ghana, in 1950. He attended school in his home country up to the undergraduate level, receiving a degree in chemical engineering from the University of Science and Technology, Kumasi (now known as the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology) in 1974. In addition to his scientific prowess, his facility with foreign languages helped set him on the path to international prominence. In the Ghanaian capital of Accra, he won the country’s national French-language competition twice, at two different levels, in 1968 and 1970.

Those awards helped Mensah win a French government fellowship in 1974 for studies in chemical engineering at Montpellier University in France. He received a Ph.D. there in 1978. Equally fluent in English, he had already completed a program at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology and received a Certificate in Modeling of Chemical Processes in 1977. Settling in the United States, Mensah took a job at Air Products and Chemicals in Allentown, Pennsylvania, from 1980 to 1983.

Mensah’s jobs in the 1980s were well suited to his strengths in basic research. From 1983 to 1986 he worked for Corning Glass Works in its fiber optics research division in Sullivan Park, New York. There he devised a new and faster method of accomplishing a fiber optics manufacturing procedure, the draw and coating process, that brought him four patents. In 1986 he joined AT&T Bell Laboratories in Georgia, part of a group of facilities that had long been one of the leading research enterprises in the United States. His work there centered on fiber optic reels that could be used at supersonic speeds in the U.S. military’s guided missile program. Mensah realized several more patents from his work in the field of missile technology.

Fiber optics, the transmission of light through materials configured as cables, was a key technology of the 1980s and 1990s, underlying many of the revolutions in communications and computer technology that led to the rise of personal computing and the Internet. In 1987 Mensah edited Fiber Optics Engineering: Processing and Applications, a collection of cutting-edge articles detailing the latest research in the field. The second collection of articles Mensah edited, Superconductor Engineering (1992), also pertained to a hot scientific area; superconductors are materials that exhibit no resistance to electricity when placed in extreme temperature environments. “The application of superconductivity in modern society can revolutionize everything from high-speed computing to magnetically levitated high-speed trains,” Mensah wrote in his introduction to the book.

Mensah’s fiber optics innovations played a role in the successful use of new missile technology that helped the United States to a quick victory in the 1991 Gulf War. He continued to add to his professional reputation as the first African American to become the national chairman of the Materials and Engineering Sciences Division of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE) and as a member of an MIT advisory board. He was also a founding member of the AIChE’s Emerging Technologies area. With these impressive credentials, Mensah had no problem finding investors when he moved to set up a company of his own, Supercond Technologies of Norcross, Georgia, in 1992.

The company had discussions with Lockheed, an aircraft manufacturer, about supplying materials for the company’s new F-22 fighter-bomber. But Mensah aimed at non-defense products as well. As U.S. defense spending dropped following the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, a host of companies, including Supercond, vied for opportunities to apply military technology to civilian enterprises, with what they hoped would be lucrative results. The company promoted an extra-strong composite material it had developed, hoping to interest manufacturers of such items as stadium seats and waste containers. “I think that many companies, even small ones, should be able to come up with dual-purpose ideas that served a defense need but have a market elsewhere,” Mensah told the Atlanta Journal and Constitution.

The approaching 1996 Atlanta Olympics helped get Supercond off to a good start. The company partnered with the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee to try to develop “smart” materials for roadway design that would allow traffic monitoring during the Games, and Mensah also hoped to use fiber-optic technology to develop new video devices that could be used in the massive Olympic logistics enterprise. “Lots of ideas are floating about out there, but what I found impressive about Supercond was that it already has assembled seed capital and is now at work on a sequence of products to provide working capital,” commented Atlanta Journal and Constitution writer Ernest Holsendolph.

Mensah won several public honors for his work. He was featured in a traveling exhibit showcasing the accomplishments of 100 black scientists and engineers, as well as in an internationally exhibited display called Black Inventors. Black-oriented websites began to mention the African-born black scientist who had helped the United States win the Gulf War. By the early 2000s, however, financial troubles had driven Supercond from business.