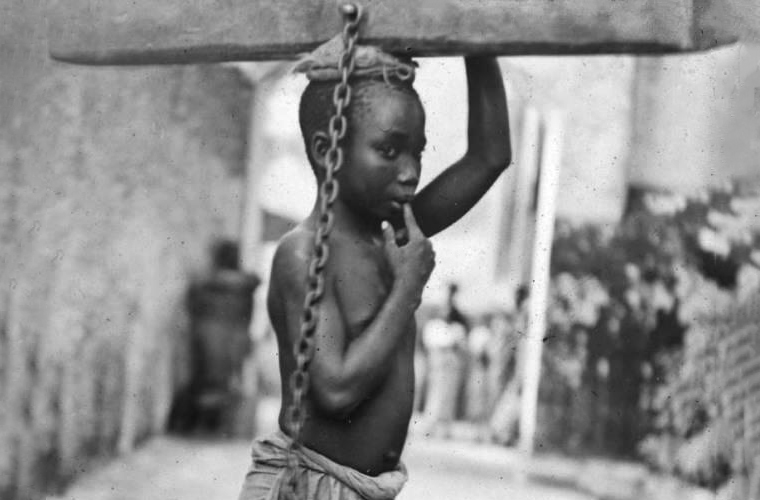

Children were an essential part of the transatlantic slave trade, and their experiences and treatment varied depending on their age, gender, and the specific circumstances of their enslavement. Many children were born into slavery, while others were captured or sold by slave traders. Some children were separated from their families and communities, while others were sold together with their families. For those who were separated from their families, the trauma of being forcibly taken from loved ones could last a lifetime.

Children were often transported across the ocean in crowded and unsanitary conditions, leading to high rates of sickness and death. Those who survived the journey were often sold as property to the highest bidder and forced to work on plantations, in mines, or in households. Many children were subjected to physical and sexual abuse and were often punished harshly for even minor infractions. Girls were particularly vulnerable to sexual violence and exploitation, as they were often forced into sexual relationships with their enslavers or other slaves. They were also expected to do domestic work, such as cooking and cleaning, in addition to their other labor.

Enslaved children had little or no access to education and were denied the opportunity to develop their own identities, cultures, and languages. Many enslaved children were forced to assimilate into the culture and language of their enslavers, which further reinforced their powerlessness and vulnerability. The impact of slavery on children was profound and long-lasting. It led to the destruction of families, communities, and cultures, and left a legacy of trauma and oppression that continues to be felt by African descendants around the world. The transatlantic slave trade represents one of the darkest periods in human history, and it is essential that we acknowledge its impact and work toward healing and reconciliation.