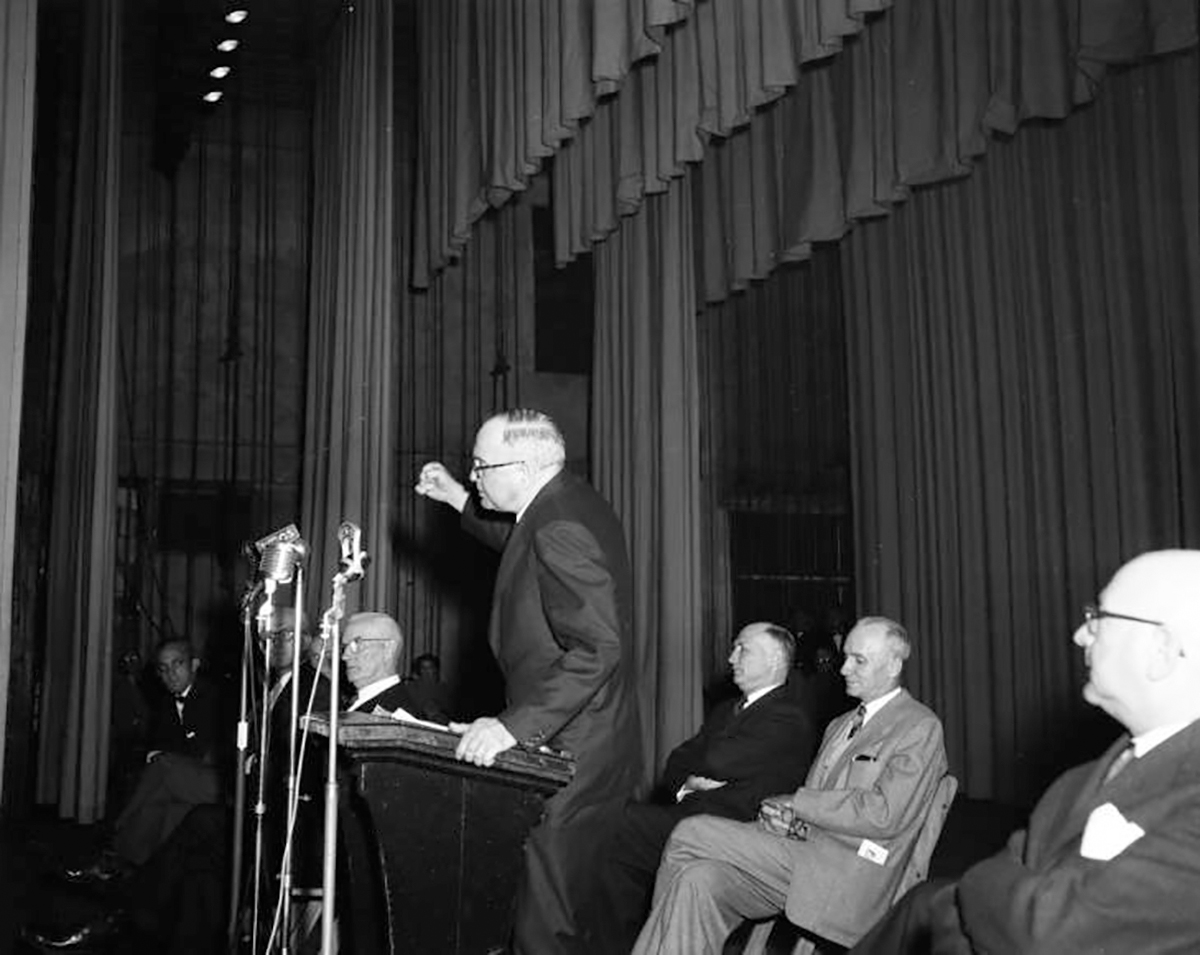

On January 26, 1956, segregationists met at the Township Auditorium in Columbia, South Carolina, and cheered as participants unfurled a Confederate flag from the balcony (far right, upper balcony). The first statewide meeting of the South Carolina Association of Citizens’ Councils featured as speakers U.S. Sen. James O. Eastland, of Mississippi; U.S. Senators J. Strom Thurmond and Olin D. Johnston, both former South Carolina governors; and state Rep. Solomon Blatt Sr., speaker of the South Carolina House.

Eastland railed against the “mongrelization of the white race” and praised South Carolina for continuing to maintain segregated schools. He asserted school segregation promoted public health, raised academic standards, preventing violence, and “promoted peaceful and harmonious race relations.” On the balcony, Gov. James F. Byrnes applauded. In 1952, Byrnes had recommended the state abandon its public school system rather than desegregate, and white voters had approved a constitutional amendment to make that action possible.

Segregationists in Mississippi founded the first White Citizens’ Councils in July 1954, after Brown v. Board of Education. On May 17, 1954, the US Supreme Court ruled that segregation of public schools violated the US Constitution, denying black children equal protection of the law guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Citizens’ Councils proliferated throughout the South, receiving an extra push in South Carolina because Brown v. Board had begun in Clarendon, South Carolina, as Briggs v. Elliott, the first of five lawsuits comprising Brown v. Board. WCC members focused on making life miserable for anyone supporting desegregation. They used their control of goods, services, and funds to punish petitioners. The segregationists fired black employees, refused to distribute goods to black businesses, called in loans and mortgages, and kicked sharecroppers and tenant farmers off the land.

That first year more than 50,000 white South Carolinians founded and joined local WCCs. Sumter, home to the state council, claimed the largest membership. S. Emory Rogers, state WCC secretary, heavily promoted the segregation-forever stance of the councils. The Summerton attorney had defended segregation in Clarendon County’s schools in Briggs v. Elliott.

When black parents in South Carolina school districts signed petitions in 1955, after Brown II recommended desegregation with “all deliberate speed,” WCC members escalated retaliation. Local white-owned newspapers published the names of petitioners, who were instantly fired from jobs, occasionally with the promise they could return if they removed their names. A few petitioners did — and didn’t get back their jobs. WCC members extended their punishment to petitioners’ family members, firing spouses and firing and evicting relatives of petitioners, and refusing sales of seed and use of farm equipment to rural petitioners and their relatives. Many black workers left the state. The WCC members inadvertently hurt themselves through the loss of customers and workers.

Prominent White Supremacists

South Carolina’s white politicians used every means possible to sustain segregation and, as this rally illustrates, openly supported the WCC.

Prominent white citizens also pushed the segregationist stance. In July 1955, The Committee of 52 came into being at a Columbia meeting led by Thomas R. Waring Jr., Charleston News, and Courier editor; William D. Workman, a politics reporter and commentator; Robert Davis, a Columbia businessman; and Farley Smith. Smith was a farmer; president of South Carolinians for Independent Electors, which focused on segregation and states rights, and son of the late U.S. Sen. Ellison D. “Cotton Ed” Smith, an aggressive white supremacist. Waring, who had been in touch with the Mississippi WCC founders, visited them in 1955 and published an editorial and three-part series promoting this segregationist movement. The organization of power brokers — members also included the president of the state bar association and president of the S.C. Farm Bureau Federation, the director of the state prisons, a Greenville insurance executive, and many bankers, business owners, and attorneys — bolstered the WCC’s legitimacy. Waring and others described council members as “patriots” and “pillars of the community.”

These white supremacists developed a resolution that advocated what they called “interposition.” In theory, interposition placed the state’s sovereignty between the segregated schools and the Brown rulings. A revamping of John C. Calhoun’s nullification theory, interposition clashed with the U.S. Constitution’s Supremacy Clause that federal law prevails when in conflict with state law or state constitutions. In August, they submitted their interposition resolution to the state’s Public School Segregation Committee, which hired six attorneys to counsel local school districts on maintaining segregation. They also published the resolution statewide in newspapers, including the Columbia Record, on August 21, 1955, inviting others to sign. Thousands did. And tens of thousands of white South Carolinians joined local councils: In the month of August alone, sixteen WCCs formed in the Summerton area, where Briggs v. Elliott began.

The Committee of 52 resolution said, in part, that “the public school system and the harmonious relationship between the white and Negro races of this state are in danger of complete disruption as a result of Federal intervention.” The resolution claimed that “outside forces and influences,” including “pressure and propaganda” by the NAACP had “lowered the will” to resist encroachments on state powers and would result in the destruction of “both education and tranquility.” On February 14, 1956, Gov. George Bell Timmerman Jr. signed an interposition resolution. On March 17, 1956, Timmerman signed legislation that banned city, county, school district, or state employment of any NAACP member.