A Global Reckoning from Africa to the Americas, India, and the Far East

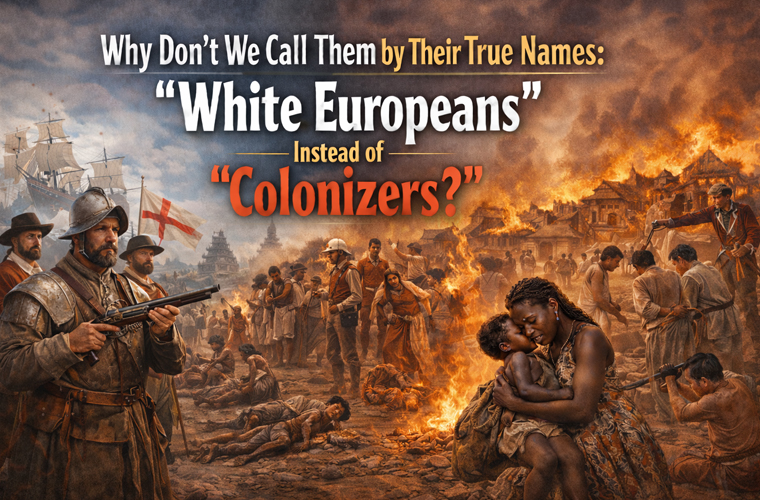

Across the Global South—from the savannas of Africa to the highlands of the Andes, the plains of India, and the rice fields of Asia—the term “colonizer” dominates discussions of historical injustice. It captures the invasions, exploitation, cultural erasure, and mass violence that reshaped entire continents. Yet this functional label often obscures the precise actors: White Europeans—the Spanish, Portuguese, British, French, Dutch, Belgians, Germans, and others—who drove these projects with shared ideologies of racial and civilizational superiority.

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 exemplifies this brazenness in Africa. Fourteen mostly White European powers, with no African representation, carved up the continent like a pie on a Berlin table. Arbitrary borders ignored ethnic realities, sparking conflicts that persist today—from Nigeria’s Biafran echoes to Rwanda’s genocide roots and Sahel insurgencies. Economies were twisted toward the extraction of raw materials: rubber from the Congo, gold and diamonds from South Africa, and cocoa from West Africa. In King Leopold II’s personal Congo Free State, millions perished from mutilations, forced labor, famine, and disease to fuel Europe’s rubber demand—hands and feet severed as punishment for unmet quotas. Arbitrary lines disrupted trade, introduced diseases, eroded health (with colonial-era height declines signaling malnutrition), and imposed White European norms through missions and schools, fostering internalized hierarchies that linger in language, aesthetics, and elite preferences.

This pattern repeated worldwide, always led by White European powers. In South America (and broader Latin America), Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors unleashed devastation from the late 15th century. The Taíno in the Caribbean faced near-total erasure through massacres, enslavement, and disease—populations plummeting from millions to near extinction by the mid-16th century. In Mexico and Peru, Cortés and Pizarro’s forces committed atrocities like the Cholula massacre, where thousands were slaughtered in alliances turned betrayal. The encomienda system enslaved Indigenous peoples for labor in mines and plantations, extracting silver and gold that enriched Europe while causing demographic collapse—estimates suggest 50–90% population loss from violence, overwork, and epidemics. Portuguese actions in Brazil mirrored this, with Indigenous enslavement and later African slave importation fueling sugar economies amid routine brutality.

In India, British rule—first through the East India Company, then the Crown—inflicted systemic horrors. The Company looted Bengal after Plassey in 1757, using torture (flogging, hot irons, chili in eyes, sexual violence) to extract revenue. Famines ravaged the subcontinent as grain was exported: millions died in Orissa (1860s) and Bengal (1943), where Churchill diverted food to British troops and stockpiles amid wartime fears, calling Indians “beastly” for “breeding like rabbits.” The 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre saw troops fire into an unarmed crowd in Amritsar, killing hundreds and wounding over a thousand in minutes, with no warning given. Railways built for extraction drained wealth, while cultural suppression and economic reorientation left lasting poverty.

Even in the Far East and Southeast Asia, White European (and later Japanese, though our focus remains European-led colonialism) powers imposed domination. The Dutch in Indonesia, the British in Malaya and Burma, and the French in Indochina extracted spices, rubber, tin, and opium through forced labor and violence. While Japanese WWII atrocities (Nanjing Massacre, comfort women) dominate later memory, earlier European colonialism set precedents: scorched-earth policies, mass displacement, and suppression of local economies. In the Philippines, under Spanish and then American rule (with European influences), similar patterns of conquest and exploitation unfolded.

The implications are profound and enduring. Arbitrary borders fuel conflict; extractive economies bred dependency and neocolonial debt; cultural disruption eroded languages, religions, and self-governance; wealth flowed outward, creating global inequalities. Populations declined from violence, famine, and disease; health and nutrition suffered long-term; internalized inferiority persists in institutions and mindsets.

We name victims precisely—Taíno, Aztec, Inca, Yoruba, Zulu, Kikuyu, Bengali, Javanese—honoring their resistance: Queen Nzinga, Tupac Amaru, the 1857 Indian uprising, Mau Mau fighters. Yet perpetrators remain vague “colonizers.” This lets descendants distance themselves: “It was systems, not people.” Naming them White Europeans confronts the racial-cultural project that invented whiteness to unify disparate groups under supremacy.

“Colonizer” indicts actions; “White European” names architects and legacies. From Berlin’s map-drawing to the conquistadors’ massacres, Company tortures, and famine policies, these were specific peoples acting on shared ideologies. Direct language sharpens truth-telling, fosters accountability, and aids healing.

In Pan-African, Indigenous, and Global South discourses, this precision rejects euphemism. Let’s say it plainly: White Europeans divided Africa, conquered the Americas, plundered India, and dominated Asia. The scars—from borders to inequality—are ours to name, confront, and heal.