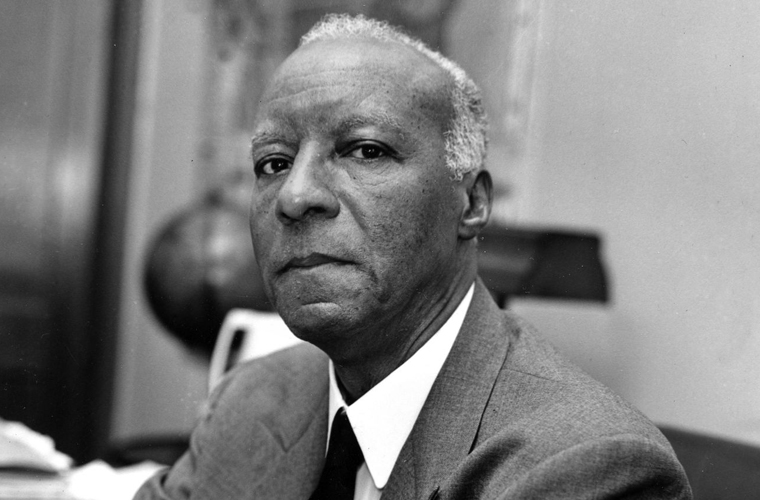

A. Philip Randolph was a prominent figure in the civil rights movement in the United States. Born on April 15, 1889, in Crescent City, Florida, Randolph dedicated his life to fighting for equality and justice for African Americans. Randolph’s activism began at a young age when he joined the Socialist Party and became involved in labor organizing. In 1925, he founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly African-American labor union. Through his leadership, the union successfully negotiated better wages and working conditions for its members, setting a precedent for future labor movements.

In addition to his work in labor organizing, Randolph was a vocal advocate for civil rights. He was a key organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. His efforts to bring attention to the economic plight of African Americans helped to galvanize support for the civil rights movement and led to significant legislative victories, including the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Randolph’s impact extended beyond the United States. He was a staunch supporter of decolonization movements in Africa and Asia, recognizing the interconnectedness of struggles for freedom and equality around the world. His advocacy for international human rights earned him widespread respect and admiration. Throughout his life, Randolph remained committed to nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience as a means of effecting social change. He believed in the power of organized collective action to bring about tangible improvements in the lives of marginalized communities.

Randolph’s legacy continues to inspire activists and leaders today. His unwavering dedication to justice and equality serves as a reminder of the ongoing struggle for civil rights and the importance of solidarity in the face of oppression. In recognition of his contributions, Randolph received numerous awards and honors, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. He passed away on May 16, 1979, leaving behind a legacy of courage, determination, and unwavering commitment to social justice.

A. Philip Randolph’s impact on the civil rights movement and labor rights continues to be felt today. His tireless advocacy and leadership have left an indelible mark on American history and serve as a testament to the power of grassroots organizing and collective action in the pursuit of a more just and equitable society.