Antonio López y López entered the world on April 12, 1817, in the modest coastal town of Comillas in Cantabria, northern Spain, where he was born into a humble family that offered few opportunities for advancement. As a young teenager, driven by the economic hardships of the time and the allure of the Spanish colonies’ booming trade, he set sail for the Americas, first arriving in Mexico before making his way to Cuba in 1831. There, in the vibrant yet brutal port city of Santiago de Cuba, he quickly immersed himself in the shadowy underbelly of the island’s economy, which was fueled by sugar plantations and an insatiable demand for labor.

López’s early ventures in Cuba centered on the illicit slave trade, a practice that, despite formal abolition efforts by Spain in the 1820s, persisted illegally well into the mid-19th century. He capitalized on this by acquiring enslaved Africans who had been smuggled ashore along Cuba’s eastern coast—often after perilous voyages from West Africa—and reselling them to plantation owners across the island’s major cities, including Havana. This ruthless commerce, intertwined with shipping and mercantile dealings, laid the foundation for his immense wealth, positioning him among a cadre of Spanish entrepreneurs who profited enormously from the transatlantic horrors of human bondage. By the 1840s, López had expanded into legitimate shipping, founding the Compañía de Vapores Correos A. López in 1850 with a modest fleet that included a hybrid sailing ship-sidewheel steamer of 400 tons. This enterprise ferried mail, passengers, and goods between Cuba, Spain, and other ports, gradually evolving into the grand Compañía Transatlántica Española in 1881, a cornerstone of Spain’s maritime empire that connected the mother country to its far-flung colonies.

As his fortune swelled, López shifted his operations back to Spain, relocating to Barcelona around the 1870s and transplanting the headquarters of his burgeoning enterprises there. In this industrial hub, he not only directed the Transatlántica line but also co-founded the Banco Hispano Colonial in 1876, serving as its inaugural president, and led the Banco de Crédito Mercantil, institutions that funneled capital into colonial ventures. His portfolio grew to include the Compañía General de Tabacos de Filipinas, which dominated the tobacco trade in the Philippines, and the Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro del Norte de España, investing heavily in northern Spain’s railroad infrastructure. Yet, even as he ascended to the pinnacle of Spanish business, López remained entangled in the slave economy, continuing to facilitate the transport of enslaved people and wielding his influence to thwart progressive social reforms in Spain’s overseas territories. As one of the world’s richest men in the late 19th century, he lobbied against abolitionist pressures and labor protections, ensuring the colonial system’s profitability endured.

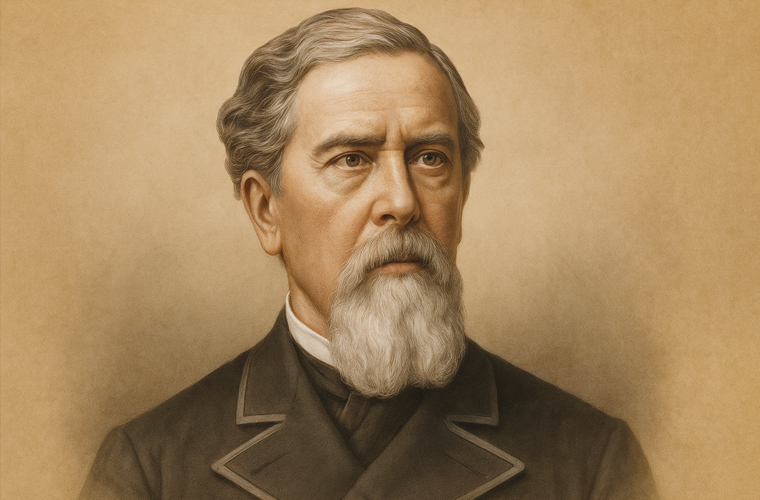

López’s stature earned him royal favor: in 1878, King Alfonso XII bestowed upon him the noble title of 1st Marquess of Comillas, a nod to his hometown and his contributions to its prosperity, along with the Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic. The following year, the acclaimed Catalan poet Jacint Verdaguer immortalized him in the epic poem L’Atlàntida, celebrating his maritime prowess. Personally, López married Lluïsa Bru Lassús, a woman from a prominent Catalan family, and together they raised four children. Their son Claudio López Bru would inherit and expand the family empire, while daughter Isabel’s marriage to the industrialist Eusebi Güell wove the López lineage into Barcelona’s elite social fabric. A devout Catholic, López also left a lasting philanthropic mark by bankrolling the establishment of the Pontifical University of Comillas at the urging of Jesuit priest Tomás Gómez Carral, with construction breaking ground in the very year of his death.

On January 16, 1883, at the age of 65, López succumbed in his opulent Barcelona residence, prompting an outpouring of national grief. King Alfonso XII himself eulogized him as one of Spain’s greatest servants, a testament to the tycoon’s outsized impact. In his honor, a towering bronze monument—titled A López y López—rose in 1884 on a prominent square at the foot of Barcelona’s Via Laietana, near the Transatlántica offices. Crafted by architect Josep Oriol Mestres and sculptor Venanci Vallmitjana, with intricate reliefs by artists like Lluís Puiggener and Joan Roig i Solé, it depicted López in heroic repose amid symbols of his shipping legacy, a gilded tribute to colonial commerce.

The statue’s glory proved fleeting amid Spain’s turbulent history. As Republican forces surged at the outset of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, it was toppled and destroyed in a wave of iconoclasm targeting symbols of the old regime. Under Franco’s dictatorship, it was meticulously rebuilt in 1944 by sculptor Frederic Marès, restoring its perch as an emblem of restored order. Yet, controversy simmered for decades, fueled by revelations of López’s slave-trading past. In the 21st century, amid global reckonings with colonial legacies—particularly following the Black Lives Matter movement’s ripple effects—a grassroots campaign in Barcelona decried the monument as a glorification of human trafficking. Petitions gathered thousands of signatures, and on March 4, 2018, city officials dismantled it once more, relocating the pieces to storage amid debates over public memory and historical accountability. Today, the empty pedestal stands as a stark reminder of the complex shadows cast by Spain’s imperial past.