Patterson v. Alabama (294 U.S. 600) was a 1935 U.S. Supreme Court decision resulting from the controversial Scottsboro Trials, which began in 1931. The high court’s unanimous decision held that the exclusion of African Americans from Alabama juries invalidated defendant Haywood Patterson’s conviction of rape by an all-white jury. The related Norris v. Alabama set the precedent that excluding blacks from juries was discriminatory and unlawful, and together Patterson and Norris showed that the Supreme Court was beginning, however slowly, to invalidate the Jim Crow system by correcting injustices as well as upholding the letter of the law.

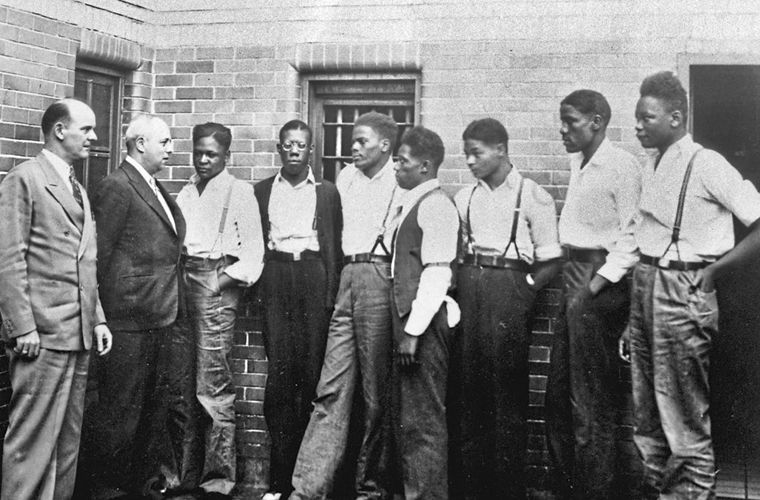

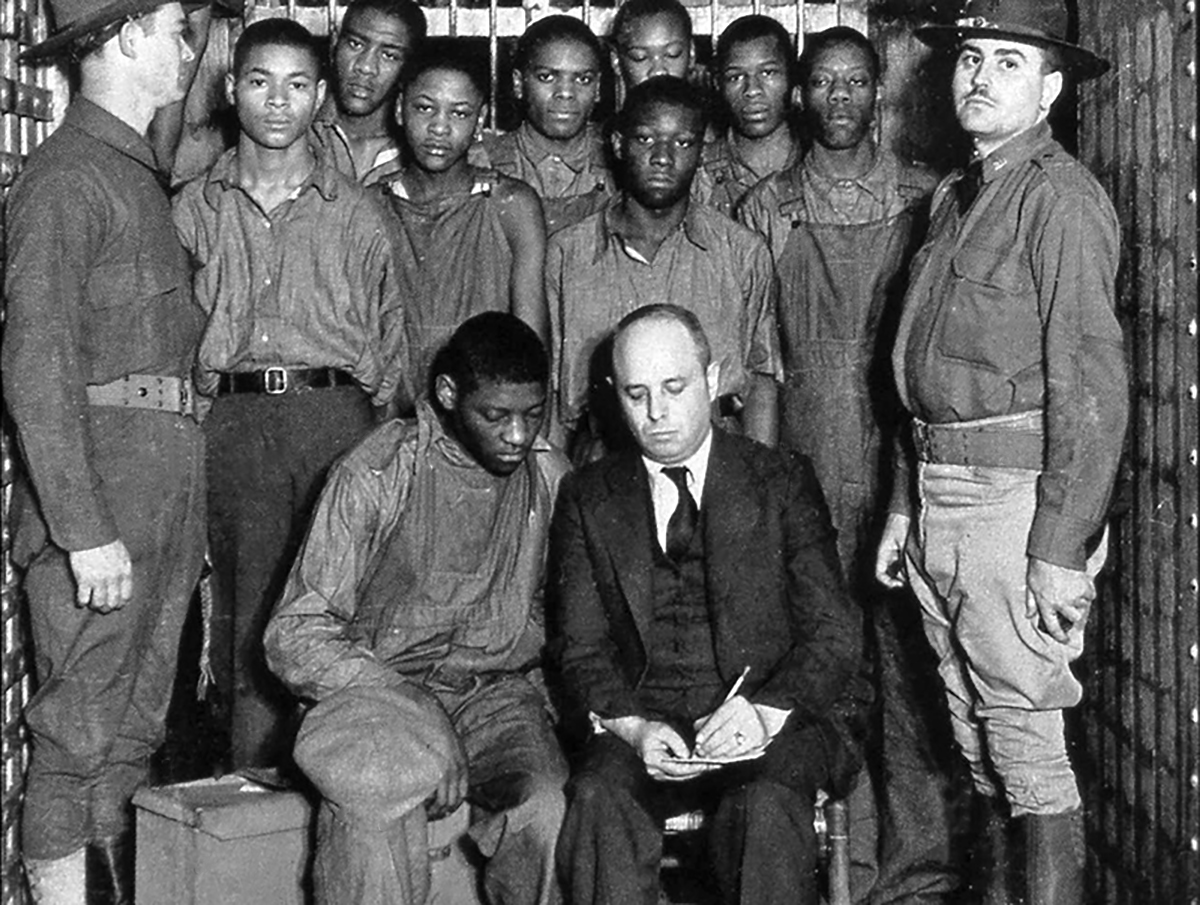

In 1931, nine African American young men, including Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris, were charged with the rape of two white women. These nine came to be known as the “Scottsboro Boys,” with “boy” being a derogatory term applied to African American men, regardless of their age, by many whites at the time. All-white juries ignored evidence of their innocence and found eight of the nine guilties, with the trial of 13-year-old Roy Wright ending in a mistrial. In 1932, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decisions in Powell v. Alabama (named for defendant Ozie, or Ozzie, Powell) on the grounds of inadequate counsel, and declared that the accused be given new trials.

Patterson was tried three times by all-white juries and convicted in all three trials. He appealed to the Alabama Supreme Court, but the appeal was rejected on a technicality. Furthermore, the bill of exceptions, a legal document that describes a party’s objections and a necessary step in appealing the case, was stricken from the records, threatening Patterson’s right to appeal the verdict to a federal court. Clarence Norris’s appeal at the same time also was rejected. The Alabama Supreme Court ruled that the exclusion of blacks from the jury rolls was not a matter of exclusion but selection. That is, the court claimed that no special effort had been made to exclude African Americans; rather, it said that no black citizen of the state met the high standards for jury duty. Both men took their cases to the Supreme Court of the United States.

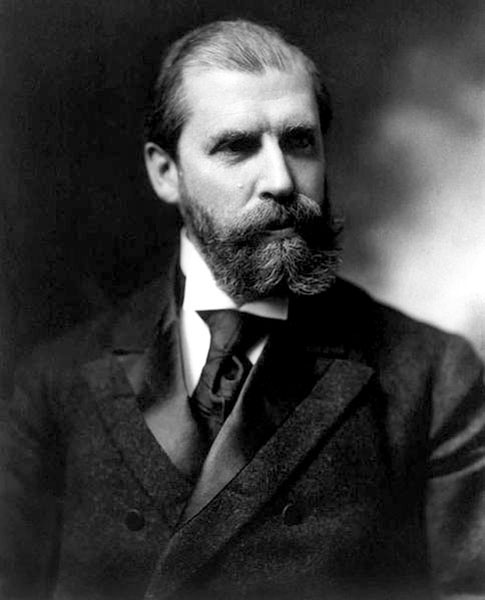

The Norris v. Alabama decision in 1935 had a crucial impact on Patterson’s case. In it, the court overturned Norris’s conviction on the basis that the absence of blacks serving on Alabama juries implied to the court that discrimination existed. Therefore, Norris had been deprived of his right to equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. (Local officials had flagrantly forged black names on the jury rolls before the retrial, an indication of their attempt to conceal racial discrimination from the higher court.) U.S. Supreme Court chief justice Charles Evans Hughes reversed the lower court’s decision and ordered a retrial for Norris.

Patterson’s case raised issues of technical legal violations taking precedence over what the High Court considered a miscarriage of justice. The Supreme Court essentially claimed that it could intervene in a situation with no obvious legal question but which still involved injustice. In this case, the court would not allow paperwork requirements to put a person’s life at risk and violate constitutional rights. Patterson had appealed his conviction on the same basis as Norris, but the state of Alabama argued that the U.S. Supreme Court had no jurisdiction because Patterson failed to raise his claim in a timely manner and file a new-trial motion before the expiration of the state court’s term. Because the bill of exception had been stricken by the Alabama Supreme Court, technically Patterson had never appealed and had not exhausted all remedies at the state level.

U.S. Supreme Court took the unusual step of remanding the case back to the Alabama Supreme Court, asserting that the Alabama judges would not have upheld Patterson’s conviction if they had known the outcome of Norris. The federal question over jury makeup that was raised in Patterson was exactly the same one that the Supreme Court had decided in Norris, and both cases deserved an equal amount of scrutiny, regardless of procedural niceties. Chief Justice Hughes, writing for the majority, claimed that the court could not only address errors in legal judgment but also see that justice was met. Implied in the ruling was the threat that, if the Alabama high court failed to overturn the verdict, the Supreme Court would review it again in the interest of justice. The Alabama Supreme Court reversed the guilty verdicts.

Along with Norris, the Patterson case showed that although the change would be halting and often only a token effort, the South could not return to a system that used all-white juries and expected the federal courts to uphold their decisions. The constitutional prohibition on racial discrimination before the law was on its way to being consistently and strongly enforced. Although this was an important precedent, the overall outcome was not as positive for Haywood Patterson. He was tried a fourth time and again found guilty. In something of a victory, given the circumstances, Patterson managed to avoid the death penalty in 1936 and was sentenced to 75 years in prison. Trapped in one of the worst prison systems in the country with little possibility of parole, he escaped in 1948. Patterson made his way to Michigan, where the governor refused to sign extradition papers to return him to Alabama. Suffering from cancer and in prison on charges of manslaughter, he died in 1952.