Before African Americans could race in the Indianapolis 500, there was the Colored Speedway Association and it’s Gold and Glory Sweepstakes. The year was 1926, and it was a perfect afternoon for racing in Indianapolis. Sparkling in the sunlight, the cars were neatly arranged on the grid. The unmistakable fragrance of racing fuel permeated the air. Anticipation was high. When the green flag dropped, the roar of the cars was nearly drowned out by that of the sold-out crowd.

The fastest drivers immediately charged to the front, jousting wheel-to-wheel for the lead in their sleek machines. Meanwhile, young Charlie Wiggins, in but his second appearance at the storied event, positioned his homely looking “Wiggins Special” on the inside of the track and settled into a steady pace. Driver after the driver passed him until by the 40th lap the sophomore had fallen to 10th place. His supporters fell silent. It looked like the hometown favorite was about to go down in defeat.

Humiliated and intent upon retaking the lead, the man chased Wiggins for another four laps—until he looked down at his fuel gauge and realized he’d been played. Wiggins had engineered his car to run on a highly efficient mixture of oil and airplane fuel. Further, by lying back in the early laps, he had also conserved his tires. While all the other drivers had to pit to change tires and refuel, Wiggins ran the entire race without stopping and took the crown.

But this wasn’t the Indianapolis 500. This was the third annual Gold and Glory Sweepstakes, a 100-mile championship race of a series for black drivers. And instead of Indianapolis Motor Speedway, it was held on a dirt track at the Indiana State Fairgrounds.

Gliding comfortably to what would be the first of his four Gold and Glory titles, Wiggins demonstrated what his friends already knew to be an unassailable fact. Where cars were concerned, nobody was more gifted than Charlie Wiggins, the man who came to be known as “The Negro Speed King.” Though he would go on to achieve national fame as the winningest African-American driver of his day, Wiggins was never allowed to demonstrate his prowess in the Indy 500.

Indiana in the 1920s was the center of the automotive universe in the United States. In addition to the Indy 500, some of the most storied marques in American history were based there, including Stutz, Duesenberg, and Studebaker. Indiana was also the northernmost stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan. With a firm grip around the throat of the state’s political structure, at one point, the Indiana Klan openly numbered the governor, as well as the mayor of Indianapolis among its members.

Fueled by KKK propaganda, segregationist attitudes were prevalent. Black drivers like Charlie Wiggins were barred from the Indianapolis 500—or any other event promoted by the 500’s sanctioning body, the American Automobile Association (AAA). Though the AAA never announced a formal ban, whenever an African-American driver like Wiggins sought entry to an event, they were turned away. While the rules were unwritten, they were very clearly understood.

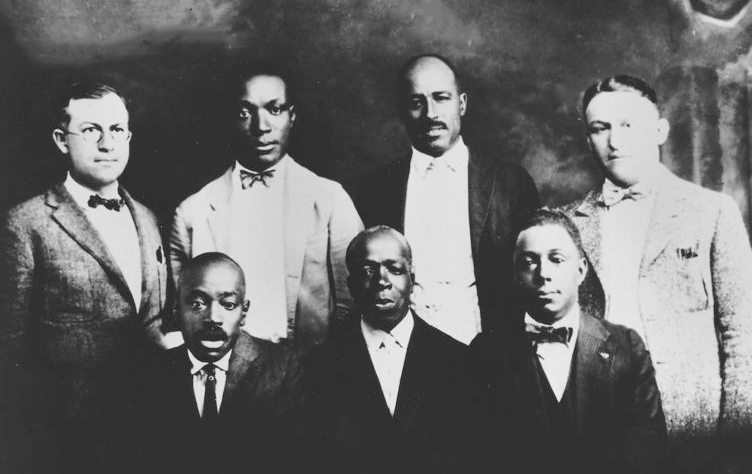

In response, a consortium of five African-American business leaders (and, it should be noted, two white businessmen) came together in 1924 to sanction a national racing series for black drivers. Dubbed the Colored Speedway Association (CSA), its championship race was the Gold and Glory Sweepstakes. Over the following 12 years, the event grew to become a national phenomenon—as did the CSA’s entire series of races, held all over the Midwest.

“The Gold and Glory Sweepstakes attracted the attention of national newspaper and newsreel agencies from coast to coast,” says Todd Gould, author of the definitive book on the series, For Gold & Glory. “At its peak, the Gold and Glory event attracted African-American crowds of up to 15,000 spectators all decked out in their Sunday best.”

Most racing fans know Willy T. Ribbs became the first African-American driver to qualify for the Indianapolis 500 in 1991. But in their day, the best Gold and Glory drivers—chief among them Charlie Wiggins—would have qualified for the 500, too.