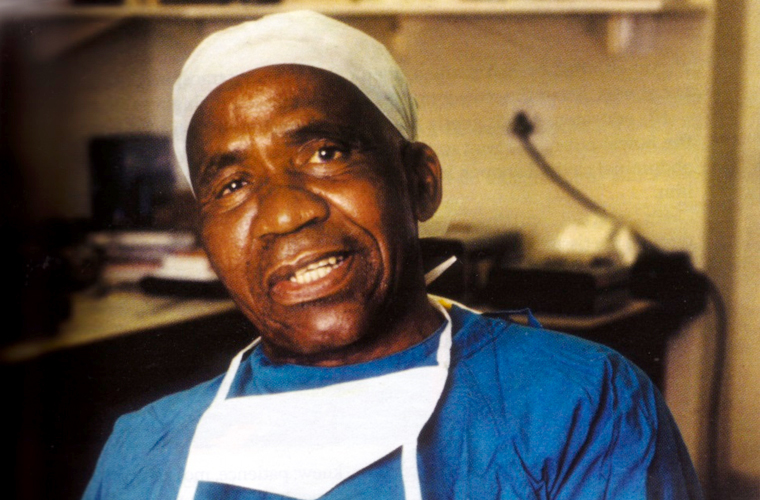

A self-taught teacher and surgical researcher, Hamilton Naki showed a natural aptitude for medicine while working as a gardener at the University of Capetown, South Africa. Despite being barred from studying medicine and officially forbidden from entering whites-only operating theaters, Naki, working as a laboratory assistant, played an important role in developing the techniques Dr. Christiaan Barnard used to perform the first human heart transplant in 1967. After the end of apartheid in 1994, Naki’s role in the pioneering transplant was exaggerated by the enthusiastic government and press of the new South Africa. In 2005 obituaries claimed that he was actually involved in the operation, which was not the case. He was, however, an important figure in the development of transplant surgery techniques, and since his death has become a symbol of the way the old regime in South Africa wasted its black citizens’ talents.

Born in Ngcangane, South Africa, in 1926, Hamilton Naki grew up in poverty and received no formal medical education. For most of his life, Naki lived under the system of apartheid, which operated in South Africa from 1948 to 1994. Under apartheid racial and ethnic groups were segregated; blacks were made citizens of “homelands” and forbidden to hold certain jobs and public positions. In 1940 at the age of 14 Naki left high school without graduating because his parents could not afford for him to continue and hitchhiked to Cape Town, where he was hired as a gardener at the University of Cape Town.

Naki’s talent as a surgeon was first noticed by Professor Robert Goetz after he asked the gardener to help look after the laboratory animals. Naki began helping out as an assistant on Goetz’s experimental work. He later explained that he learned his surgical skills by watching others, saying “I stole with my eyes,” according to the Economist. Before long Naki was performing dissections and quickly acquired a reputation in the hospital for his skills, especially for the way he handled delicate membranes. When Goetz left the University of Cape Town, Naki served as laboratory assistant to Dr. Christiaan Barnard, according to the New York Times. Barnard was impressed by Naki’s skills, in particular, his ability to carry out very fine stitching in blood vessels.

Because of the apartheid laws, Naki was forbidden from training as a surgeon and from working in the operating theater. But Barnard allowed him to teach his students and to assist in demonstrations. Naki’s skills were so highly respected that students would go to him to be shown how to perform particular techniques. In all, he helped in the education and training of over 3,000 surgeons, according to several news sources. His hand in training these medical students may have been exaggerated, according to a report by Michael Wines in the New York Times. Wines interviewed Dr. Rosemary Hickman, with whom Naki worked from 1967 to 1995. Hickman noted the exaggeration, but confirmed that “Naki was instrumental in a program in which second-year medical students were trained in anatomy by observing surgery on anesthetized pigs.” She also noted that he “helped teach licensed doctors how to use laparoscopes, used for a form of minimally invasive surgery, after the technique was introduced to South Africa.”

Most controversially Naki was reported to have been involved in Barnard’s 1967 operation to transplant the heart of donor Denise Darvall at the Groote Shuur Hospital. In the years following the 1994 democratic election in South Africa, Naki’s role in the operation became a matter of pride to black South Africans. He became an example of what might have been possible for millions of people had their talents not been wasted by the apartheid system. Naki was celebrated as the black surgeon who had secretly been allowed to remove and prepare the donor’s heart for Barnard. When he died in 2005 obituaries in journals such as the Economist, the British Medical Journal and the Lancet all made inflated claims to this effect on Naki’s behalf, claims the publications later retracted. Mr. David Dent, who worked with Naki at the time of Barnard’s transplant, confirmed to Wines that “he had a very good hand, but he never went to the hospital, or into the hospital, or saw a human.”

Naki was certainly an important figure in the development of the techniques Barnard used to perform his groundbreaking transplant operation. Naki performed many successful transplants on animals, developing and refining the procedures that would later make human transplants possible. His ability as a surgeon is not in doubt, and he is certainly a key figure in the history of transplant surgery. “He has skills I don’t have,” Barnard told the Associated Press in 1993, according to the Washington Post. “If Hamilton had had the opportunity to perform, he would have probably become a brilliant surgeon.” But Naki was never given the opportunity. Although he was an important part of the research team and appeared—identified as a gardener—with Barnard in publicity shots, he was not present in the operating theater when the first human heart transplant took place. Perhaps because the apartheid system meant that his role had remained secret it was later possible for an overenthusiastic media to embellish his story. Feeling the pressure in old age, and perhaps even beginning to believe it himself, Naki eventually went along with the story of his participation in the operation itself.

Naki’s achievements in the context of strict segregation, limited education, and poverty remain impressive. Naki had a strong Christian faith and spent his lunch hours reading the Bible to alcoholics, drug addicts, and the homeless in a cemetery near to the hospital. He lived his whole life in a one-room house without electricity or running water. He was unable to afford an education for his own four children. Some reports indicate that Naki retired in 1991 on a gardener’s salary and died penniless. However, Hickman told Wines that Naki had been promoted to laboratory assistant and retired from that position. It is difficult to untangle the truth from myth, especially now that both Barnard and Naki have died. Yet Hickman assured Wines that “Naki was an honest man” and confirmed his considerable talents. In 2002 he received South Africa’s highest honor, the Order of Mapungubwe; in 2003 he received an honorary degree in medicine from the University of Cape Town. He died on May 29, 2005, aged 78.