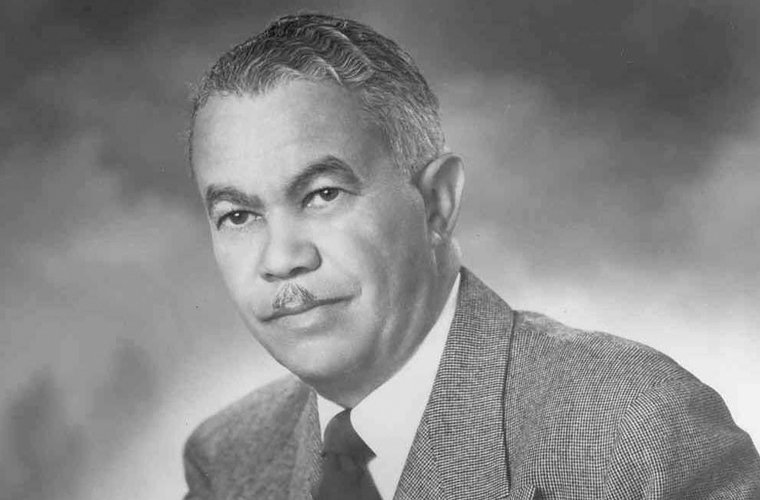

Paul Revere Williams was born in Los Angeles on February 18, 1894, to Lila Wright Williams and Chester Stanley Williams who had recently moved from Memphis with their young son, Chester, Jr. When Paul was two years old his father died, and two years later his mother died. The children were placed in separate foster homes. Paul was fortunate to grow up in the home of a foster mother who devoted herself to his education and to the development of his artistic talent.

At the turn of the 20th century, Los Angeles was a vibrant multi-ethnic environment with a population of only 102,000 of which 3,100 were African American (U.S. Census 1900). During Williams’ youth, the California dream attracted people from across the United States, and they mixed together with little prejudice. Williams later reported that he was the only African American child in his elementary school, and at Polytechnic High School he was part of an ethnic mélange. However, in high school, he experienced the first hint of adversity when a teacher advised him against pursuing a career in architecture because he would have difficulty attracting clients from the majority white community and the smaller black community could not provide enough work.

Williams did not give up. Confident in his strengths, he simultaneously pursued architectural education and professional experience with Los Angeles’ leading design firms while developing social and business networks. Certified as a building contractor in 1915, he was licensed as an architect by the State of California in 1921. Earning accolades in architectural competitions and the respect and encouragement of his employers, Williams opened his own practice and become the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1923.

Southern California’s real estate landscape boomed during the 1920s. Williams’ early practice flourished through his growing skills as a designer of small, affordable houses for new homeowners and larger, historic revival-style homes for more affluent clients in Flintridge, Windsor Square, and Hancock Park.

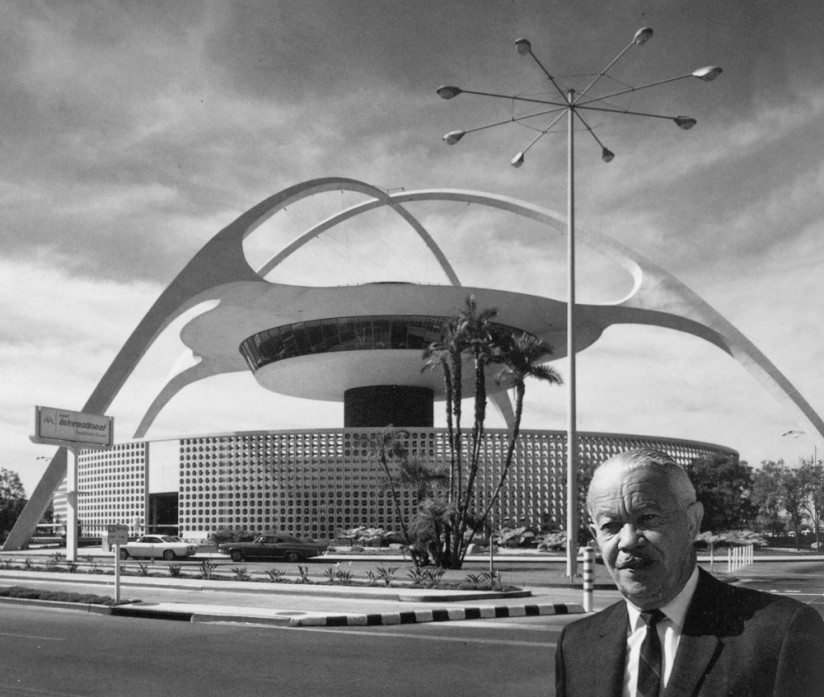

As his reputation grew, his practice expanded to include buildings now considered landmarks: MCA, Saks Fifth Avenue, Palm Springs Tennis Club, and Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building. The private residences he designed for leaders in business and entertainment became legendary: actor Bert Lehr, comedians Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, dancer Bill (Bojangles) Robinson, popular entertainer Frank Sinatra and the entrepreneurial Cord and Paley families. The residential design would remain an important part of his practice, but commercial, institutional, and public commissions became increasingly significant as did his work beyond Southern California, across the nation and the world.

In the course of his five-decade career, Williams designed thousands of buildings, served on many municipal, state, and federal commissions were active in political and social organizations earning the admiration and respect of his peers. He frequently donated his time and skills to projects he believed furthered the health and welfare of young people, African Americans in Southern California, and greater society. In 1957, he was the first African American elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects.

Paul R. Williams retired from practice in 1973 and died in 1980 at the age of 85.

Williams was awarded AIA’s 2017 Gold Medal, the highest annual honor recognizing individuals whose work has had a lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture.