When you think of the Trail of Tears, you likely imagine a long procession of suffering Cherokee Indians forced westward by a villainous Andrew Jackson. Perhaps you envision unscrupulous white slaveholders, whose interest in growing a plantation economy underlay the decision to expel the Cherokee, flooding in to take their place east of the Mississippi River.

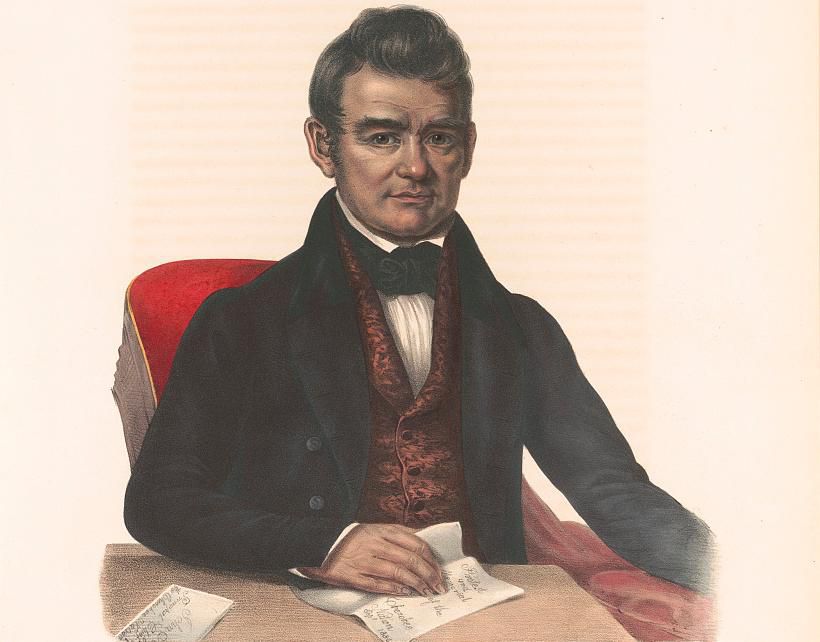

What you probably don’t picture are Cherokee slaveholders, foremost among them Cherokee chief John Ross. What you probably don’t picture are the numerous African-American slaves, Cherokee-owned, who made the brutal march themselves, or else were shipped en masse to what is now Oklahoma aboard cramped boats by their wealthy Indian masters. And what you may not know is that the federal policy of Indian removal, which ranged far beyond the Trail of Tears and the Cherokee, was not simply the vindictive scheme of Andrew Jackson, but rather a popularly endorsed, congressionally sanctioned campaign spanning the administrations of nine separate presidents.

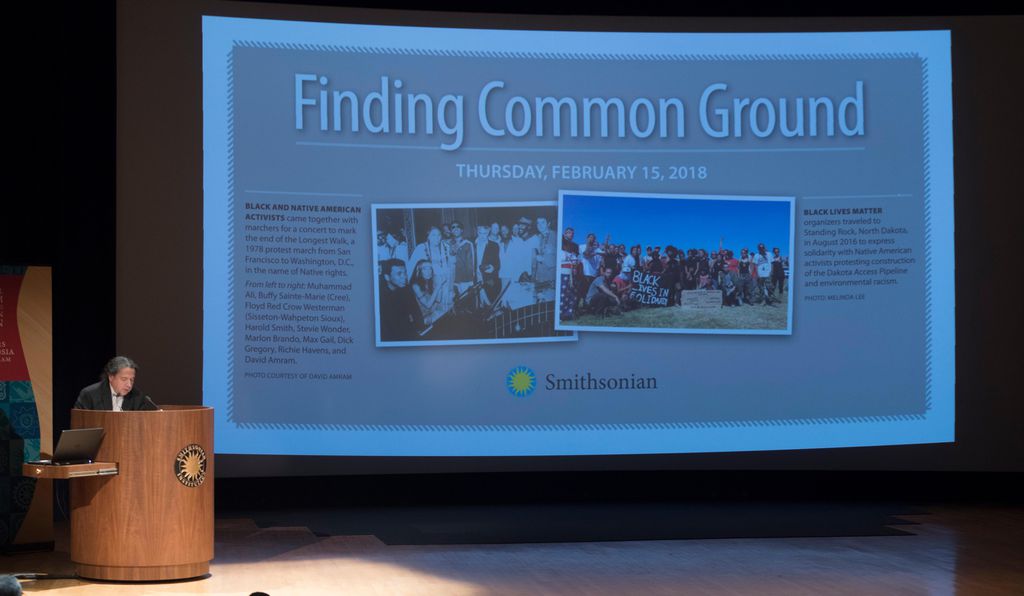

These uncomfortable complications in the narrative were brought to the forefront at a recent event held at the National Museum of the American Indian. Titled “Finding Common Ground,” the symposium offered a deep dive into intersectional African-American and Native American history.

For museum curator Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche), who has overseen the design and opening of the widely lauded “Americans” exhibition now on view on the museum’s third floor, it is imperative to provide the museum-going public with an unflinching history, even when doing so is painful.

“I used to like history,” Smith told the crowd ruefully. “And sometimes, I still do. But not most of the time. Most of the time, history and I are frenemies at best.” In the case of the Trail of Tears and the enslavement of blacks by prominent members of all five so-called “Civilized Tribes” (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole), Smith went one step further, likening the ugly truth of history to a “mangy, snarling dog standing between you and a crowd-pleasing narrative.”

“Obviously,” Smith said, “the story should be, needs to be, that the enslaved black people and soon-to-be-exiled red people would join forces and defeat their oppressor.” But such was not the case—far from it. “The Five Civilized Tribes were deeply committed to slavery, established their own racialized black codes, immediately reestablished slavery when they arrived in Indian territory, rebuilt their nations with slave labor, crushed slave rebellions, and enthusiastically sided with the Confederacy in the Civil War.”

In other words, the truth is about as far a cry from a “crowd-pleasing narrative” as you could possibly get. “Do you want to hear that?” Smith asked the audience. “I don’t think so. Nobody does.” And yet, Smith is firm in his belief that it is a museum’s duty to embrace and elucidate ambiguity, not sweep it under the rug in the pursuit of some cleaner fiction.

Tiya Miles, an African-American historian at the University of Michigan, agrees. At the “Finding Common Ground” event, she meticulously laid out primary-source evidence to paint a picture of Indian/African-American relations in the years leading up to the Civil War. Native Americans, she said, had themselves been enslaved, even before African-Americans, and the two groups “were enslaved for approximately 150 years in tandem.” It wasn’t until the mid-18th-century that the bondage of Native Americans began to wane as Africans were imported in greater and greater numbers. Increasingly, where white colonists viewed Africans as little more than mindless beasts of burden, they saw Native Americans as something more: “noble savages,” unrefined but courageous and fierce.

Perversely, Native American ownership of black slaves came about as a way for Native Americans to illustrate their societal sophistication to white settlers. “They were working hard to comply with government dictates that told native people that in order to be protected and secure in their land base, they had to prove their level of ‘civilization,’” Miles explained.

How would slave ownership prove civilization? The answer, Miles contends, is that in capitalism-crazed America, slaves became tokens of economic success. The more slaves you owned, the more serious a businessperson you were, and the more serious a businessperson you were, the fitter you were to join the ranks of “civilized society.” It’s worth remembering, as Paul Chaat Smith says, that while most Native Americans did not own slaves, neither did most Mississippi whites. Slave ownership was a serious status symbol.

Smith and Miles agree that much of early American history is explained poorly by modern morality but effectively by simple economics and power dynamics. “The Cherokee owned slaves for the same reasons their white neighbors did. They knew exactly what they were doing. In truth,” Smith said, the Cherokee and other “Civilized Tribes were not that complicated. They were willful and determined oppressors of blacks they owned, enthusiastic participants in a global economy driven by cotton, and believers in the idea that they were equal to whites and superior to blacks.”

None of this lessens the very real hardship endured by Cherokees and other Native Americans compelled to abandon their homelands as a result of the Indian Removal Act. Signed into law in the spring of 1830, the bill had been rigorously debated in the Senate (where it was endorsed with a 28-19 vote) that April and in the House of Representatives (where it prevailed 102-97) that May. Despite a sustained, courageous campaign on the part of John Ross to preserve his people’s property rights, including multiple White House visits with Jackson, in the end, the influx of white settlers and economic incentives made the bill’s momentum insuperable. All told, the process of removal claimed more than 11,000 Indian lives—2,000-4,000 of the Cherokee.

What the slaveholding of Ross and other Civilized Nations leaders does mean, however, is that our assumptions regarding clearly differentiated heroes and villains are worth pushing back on.

“I don’t know why our brains make it so hard to compute that Jackson had a terrible Indian policy and radically expanded American democracy,” Smith said, “or that John Ross was a skillful leader for the Cherokee nation who fought the criminal policy of removal with every ounce of strength, but also a man who deeply believed in and practiced the enslavement of black people.”

As Paul Chaat Smith said to conclude his remarks, the best maxim to take to heart when confronting this sort of history may be a quote from African anti-colonial leader Amílcar Cabral: “Tell no lies and claim no easy victories.”