A Towering Figure in American Cinema

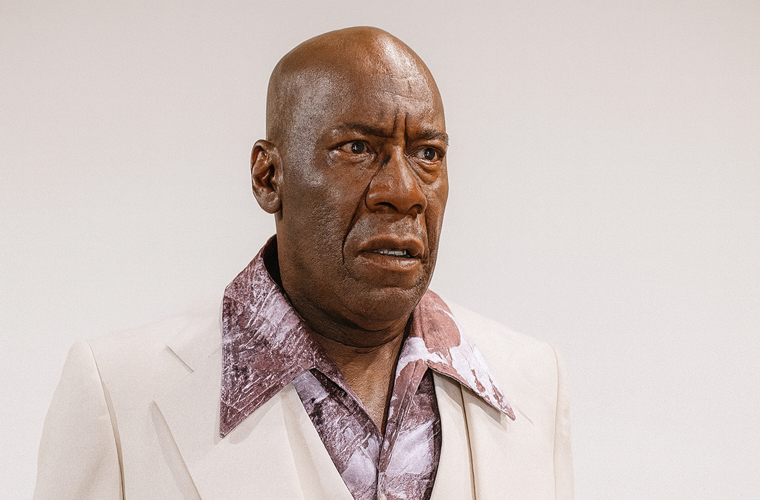

Julius W. Harris was a formidable presence in American film and television, known for his deep voice, imposing stature, and ability to portray complex characters ranging from menacing villains to stoic mentors. Over a career spanning more than three decades, he appeared in over 70 films and countless television episodes, leaving an indelible mark on blaxploitation cinema and beyond. Born into a world of jazz and performance, Harris’s journey from wartime medic to silver-screen icon exemplifies resilience and late-blooming talent.

Harris entered the world on August 17, 1923, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a city pulsing with cultural energy during the Harlem Renaissance’s echo. His father was a musician, immersed in the vibrant sounds of the era. At the same time, his mother had danced at the legendary Cotton Club in New York City—a hotspot for Black entertainers that symbolized both glamour and segregation’s harsh realities. These roots in performance would later influence Harris’s own path, though he took a circuitous route to the stage.

Before fame, Harris served as a medic in the U.S. Army during World War II, tending to the wounded amid the chaos of global conflict. Returning home, he worked as a nurse and bouncer in New York City’s jazz clubs, rubbing shoulders with the era’s musical greats and witnessing the raw energy of Harlem nightlife. It was in these smoke-filled venues that he first encountered aspiring actors, but it wasn’t until a daring audition at age 41 that his life pivoted dramatically.

Harris’s entry into acting was nothing short of serendipitous. On a whim—prompted by friends in the struggling theater scene—he auditioned for a role in Michael Roemer’s 1964 independent film Nothing But a Man. Cast as Will Anderson, the stern yet loving father in this poignant drama about Black life in the rural South, Harris starred opposite Ivan Dixon and Abbey Lincoln. The film, critically acclaimed for its unflinching portrayal of racial and class struggles, marked his debut and set the tone for a career defined by authenticity and gravitas.

From there, Harris joined the prestigious Negro Ensemble Company in New York City, a groundbreaking theater group that championed Black stories. He made his Broadway debut in the Pulitzer Prize-winning play No Place to Be Somebody (1969), further honing his craft alongside luminaries like Roscoe Lee Browne and Moses Gunn. These stage roots grounded his later screen work, allowing him to infuse roles with a depth drawn from lived experience.

The 1970s propelled Harris to wider recognition, as he became a staple of the blaxploitation genre—a cinematic movement that empowered Black heroes while often casting Harris as a formidable antagonist. His breakout film role came in 1972’s Super Fly, where he played the drug lord Scatter, a character whose slick menace embodied the era’s streetwise edge. That same year, he menaced Robert Hooks as the crime boss Mr. Big in Trouble Man, a taut thriller that showcased his ability to dominate scenes with minimal dialogue.

Harris’s most iconic role arrived in 1973 as Tee Hee Johnson in the James Bond adventure Live and Let Die. Portraying the steel-jawed henchman to Yaphet Kotto’s Mr. Big, Harris brought a chilling physicality to the part—his prosthetic claw arm becoming a memorable Bond villain trope. He followed this with back-to-back collaborations with Fred Williamson in Black Caesar and Hell Up in Harlem (both 1973), playing the loyal enforcer Mr. Gibbs in gritty tales of revenge and Harlem underworlds.

Harris’s filmography reads like a who’s who of ’70s cinema, blending action, drama, and occasional comedy. He shared the screen with Sidney Poitier and Bill Cosby in the heist comedy Let’s Do It Again (1975) as the sly Bubbletop Woodson, faced off against Richard Roundtree’s Shaft in Shaft’s Big Score! (1972), and even tangled with a giant ape in the 1976 remake of King Kong. Later highlights included a turn as Joseph in the Hemingway adaptation Islands in the Stream (1977) opposite George C. Scott, and Ugandan dictator Idi Amin in the TV movie Victory at Entebbe (1976). His final film credit came in 1994’s cult horror-comedy Shrunken Heads, a fittingly eccentric capstone to a diverse oeuvre.

While films defined his legacy, television offered Harris steady work and variety. He guest-starred on beloved series like Sanford and Son (1977), Good Times (1976), and The Jeffersons (1984), often bringing his signature intensity to comedic or dramatic beats. In more serious fare, he appeared on Kojak (1977), The Incredible Hulk (1979), and Murder, She Wrote (1991), showcasing his range from tough cops to haunted everymen. Harris also lent gravitas to miniseries such as Rich Man, Poor Man (1976) and The Blue and the Gray (1982), and made recurring appearances on Cagney & Lacey (1983–1986). His final TV role was a 1997 episode of ER, proving his enduring appeal even into his later years.

Harris’s career was more than prolific—it was pioneering. As one of the few Black actors consistently landing villainous yet nuanced roles in mainstream Hollywood, he helped shatter color barriers during a time when opportunities for performers of color were scarce. Directors prized his 6’4″ frame and booming baritone, but it was his commitment to authentic Black narratives that resonated most. From indies like Nothing But a Man to blockbusters like Live and Let Die, Harris embodied the complexity of the Black American experience, influencing actors like Samuel L. Jackson and Laurence Fishburne. Away from the cameras, Harris kept a low profile, raising two children—daughter Kimberly and son Gideon—in relative privacy. He never sought the spotlight for its own sake, preferring the craft over celebrity.

On October 17, 2004—one day shy of what would have been his 82nd birthday—Harris succumbed to heart failure at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills, California. Cremated and interred in his beloved Philadelphia, he left behind a body of work that continues to captivate audiences. Julius Harris wasn’t just an actor; he was a force—a reminder that true power lies in presence, persistence, and the stories we tell.