Before Meredith “Flash” Gourdine became a world-renown engineer and physicist, he was a silver medalist in the 1952 Olympic Games. Ultimately better known for his work in thermal management technology than for his 24-foot long jump, he specialized in research relating to electrodynamics, which is a method used to disperse fog and smoke. Other applications of electrodynamics include refrigeration, desalination of seawater, and pollutant reduction in smoke. The companies he founded worked on purifying the air and converting low-grade coal into inexpensive, transportable, and high-voltage electrical energy. They produced a commercial air-pollution deterrent, a high-powered industrial paint spray, and a device to eliminate fog above airports. He died in 1998 with seventy patents to his name.

Gourdine was born in Newark, New Jersey, on September 26, 1929. He was raised in Brooklyn, New York, where his father was a painter and a janitor. After school at Brooklyn Tech High School, he worked eight hours a day on painting jobs with his father. Gourdine once told the New York Times, “My father said, ‘If you don’t want to be a laborer all your life, stay in school.’ It took.” He earned a bachelor’s degree in engineering from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. In 1960, on a Guggenheim fellowship, he earned a doctorate in engineering science from the California Institute of Technology.

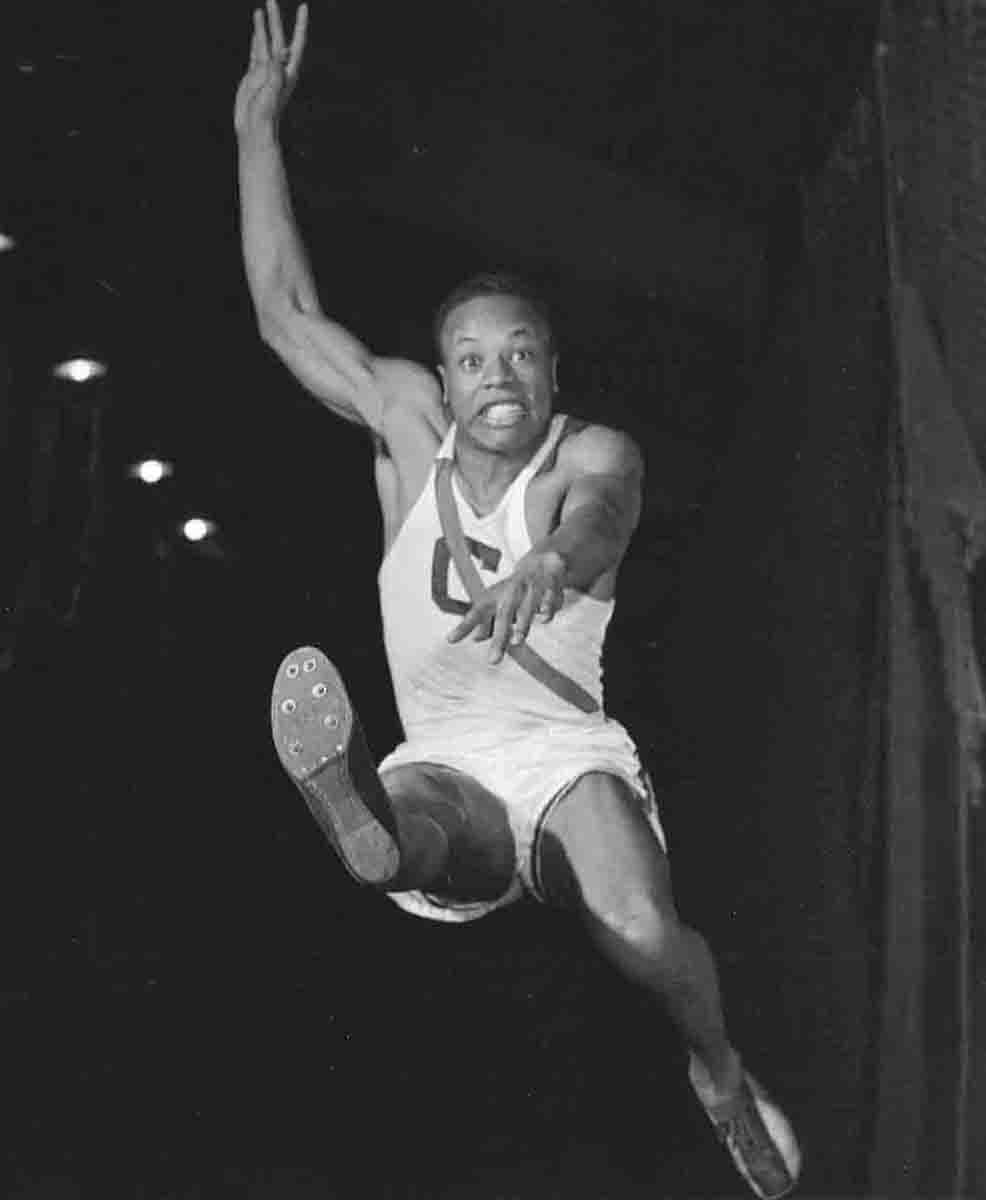

Gourdine was a swimmer in high school and did not start running until his senior year when he joined the track team. He never won a race there, but he did earn a swimming scholarship offer from the University of Michigan. Instead, he went to Cornell and paid his way for most of the first two years. His sports career flourished at Cornell, where at 6 feet and 175 pounds he earned the nickname “Flash.” He competed in the sprints, low hurdles, and long jump. He earned four titles in the championships of the Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletes of America and five titles in the Heptagonal Games. In 1952, he was on the five-member Cornell team that finished second to Southern California, which had thirty-six athletes, in the National Collegiate Athletic Association championships.

After his successful track career at Cornell, Gourdine experienced his greatest achievement and greatest frustration in the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland. He finished second in the long jump, an inch and a half behind American team member Jerome Biffle. Biffle won the gold medal in the long jump at 24 feet 10 inches. “I would have rather lost by a foot,” he said as he recalled the event years later, according to the New York Times. “I still have nightmares about it.” After graduation from Cornell and the Olympics, Gourdine became an officer in the United States Navy.

When he was out of the Navy, Gourdine went into research in the private sector. He got a job on the technical staff of the Ramo-Woolridge Corporation in 1957. In 1958, he became a senior research scientist at the Caltech Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He was a lab director of the Plasmodyne Corporation from 1960 to 1962 and was chief scientist of the Curtiss-Wright Corporation from 1962 to 1964. In 1964, he served on the president’s panel on energy. After years of working in other people’s labs, Gourdine scraped together $200,000 from friends and opened his own research and development laboratory, Gourdine Systems, in Livingston, New Jersey. The company grew to employ 150 people.

In 1973, Gourdine founded Energy Innovations in Houston to produce direct-energy conversion devices. He built Energy Innovations into a multi-million dollar company and was the chief executive there until his death. Later in his career, he focused his efforts on heating and cooling systems based on the conversion and transfer of thermal energy. His work in this field is represented by his collection of patents from 1989 to 1996.

Gourdine was one of the first, and one of the most respected, scientists in electrodynamics (EGD), which is the generation of energy from the motion of gas molecules that have been ionized, or electrically charged, under high pressure. Gourdine had a great talent for inventing practical applications for this complex procedure. He is best known for his invention of various electrostatic precipitator systems, for which he earned his first patents from 1971 to 1973.

Gourdine’s patents include an application called Incineraid, which helps remove smoke from burning buildings. He patented a method of removing fog from airport runways in 1987. These systems clear the air by introducing a negative charge to airborne particles: once negatively charged, the particles are electromagnetically attracted to the ground, and so drop down, to have their former place taken by cleaner air. Gourdine also won patents for applications of EGD to circuit breakers, acoustic imaging, air monitors, and coating systems, as well as the Focus Flow Heat Sink, which is used to cool computer chips.

As Gourdine aged, he suffered multiple strokes and complications from diabetes. He gradually went completely blind. He died in Houston, Texas on November 20, 1998, at age 69. He was serving as the president of Energy Innovation, Inc. of Houston, Texas at the time of his death. He was survived by his wife, Carolina Baling Gourdine, a son, three daughters from a previous marriage, and five grandchildren.