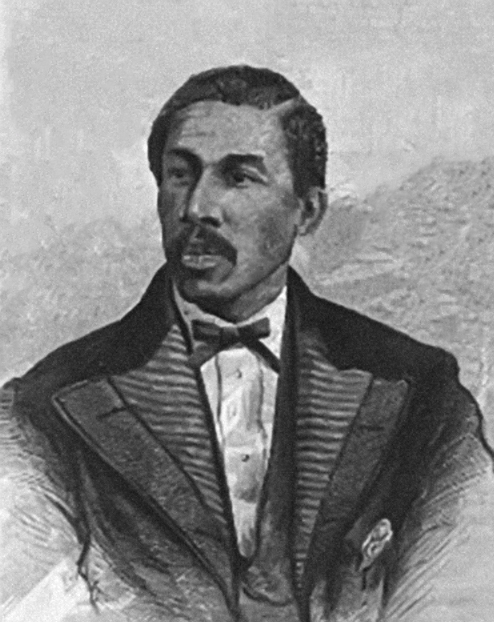

Octavius V. Catto fought for a variety of causes related to desegregating public services and preventing discrimination against African Americans in politics and sports.

Octavius V. Catto fought for a variety of causes related to desegregating public services and preventing discrimination against African Americans in politics and sports.

A tumultuous, racially polarized Election Day in Philadelphia set the stage for the October 10, 1871, murder and martyrdom of Octavius V. Catto (b. 1839), an African American leader who struggled against segregation and discrimination in transportation, sports, politics, and society.

Election Day in 1871, just one year after the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution restored voting rights for African Americans in Pennsylvania, was mired in the bloodshed of many. Fighting between angry white Democrats and African Americans, who aligned with the Republican Party, expanded into a riot in the predominantly African American neighborhood along eastern Lombard and South Streets. Police did little to intervene.

In the years prior to the election, Catto had worked to help the nation realize its founding democratic vision through actions to increase educational opportunities, desegregate trolley cars, increase voting opportunities for African Americans, and (as a notable local athlete) to integrate baseball. Fierce opposition to Catto’s activism and the general progress of African Americans contributed to his eventual murder. At the time of the election, he was an instructor at the Institute for Colored Youth (later Cheyney University), at Sixth and Lombard Streets. In a twist of tragic irony, he beseeched Mayor Daniel Fox (1819-90) to consider providing greater protection to black voters. He and his colleagues decided to close the Institute early due to risks to staff and students.

Catto also was a major and inspector general of the 5th Brigade, 1st Division of the National Guard of Pennsylvania, a position that required him to have a horse, sword, and sidearm (pistol). On this Election Day, he went to the Philadelphia branch of the Freedmen’s Bank (a powerful symbol of black empowerment through cooperative economics) at 919 Lombard to withdraw twenty dollars to purchase a gun. On his way there, he encountered white attackers, whom he narrowly escaped. Shortly thereafter, Catto met with his friend Cyrus Miller and the two traveled to a pawnshop on Walnut Street where Catto purchased a six-shot revolver.

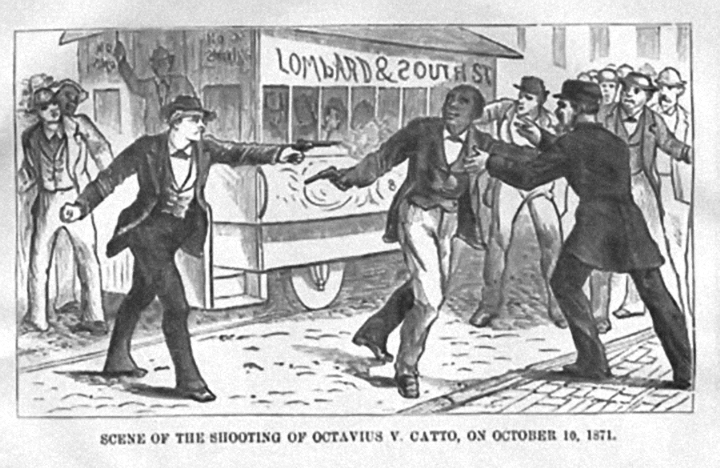

This depiction of the murder of Octavius V. Catto was based on testimony provided by witnesses during Frank Kelly’s trial in 1877.

This depiction of the murder of Octavius V. Catto was based on testimony provided by witnesses during Frank Kelly’s trial in 1877.

Around 3 p.m. the two friends parted and Catto started for home (814 South Street), where he had stored ammunition for his newly purchased firearm. Around 3:30 p.m., moments from his home, Catto passed two white men, Edward Reddy Denver and Frank Kelly. Seconds after crossing paths and without any words being exchanged, Kelly pulled a pistol and fired into Catto, who staggered backward as he clutched his bleeding wound. Catto attempted to flee to safety behind a streetcar to no avail. Kelly discharged his revolver at close range with no regard for the multitude of onlookers. Catto collapsed lifeless into the arms of an approaching police officer.

The funeral of Octavius Catto created a moment of mourning that provided a distinct departure from the violence and rioting that led to his demise. The service, held in the City Armory at Broad and Race Streets, was a national event with attendees from numerous states including Delaware, Washington, New York, and Mississippi. The funeral procession, beginning at 7 a.m. in the drizzling rain at Broad and Race Streets and ending at Lebanon Cemetery in Philadelphia (the remains were later brought to Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania after Lebanon closed), included regimental guards, students, faculty, and graduates from the Institute for Colored Youth, preachers, politicians, and more than 5,000 mourners. Catto was eulogized in pulpits throughout the country.

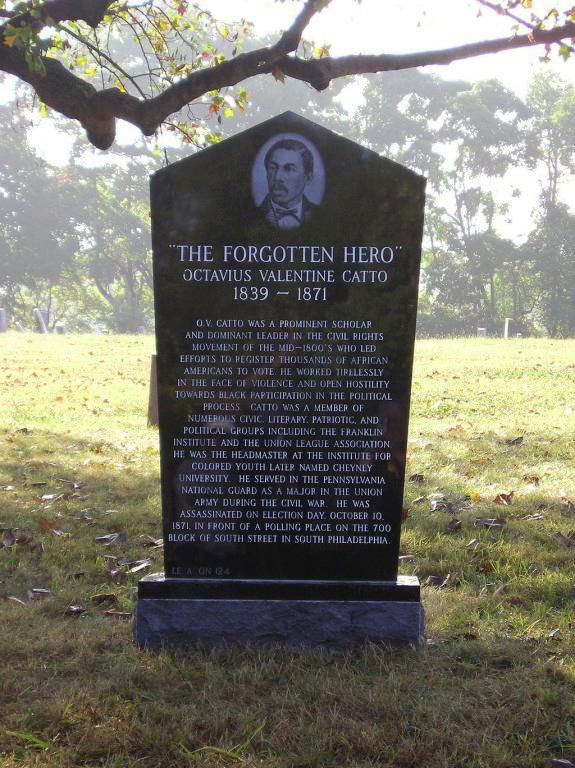

Octavius V. Catto’s grave in Eden Cemetery had just a simple marker before the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund installed this descriptive tribute to Catto’s legacy in 2007.

Octavius V. Catto’s grave in Eden Cemetery had just a simple marker before the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund installed this descriptive tribute to Catto’s legacy in 2007.

For more than a century after his death, Octavius Catto has been remembered for his achievements and sacrifices. Schools, Masonic lodges, and university residence halls carry his name, and he has been inducted into the Negro League Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2007, the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund erected a headstone at his gravesite in Collingdale with the inscription “The Forgotten Hero.” In 2010, Temple University Press published a new Catto biography, Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America. In 2011, the City of Philadelphia contributed $500,000 toward a $2 million fund-raising campaign for a monument at City Hall to honor Catto, his life, and the work that ended in tragedy on Election Day 1871.