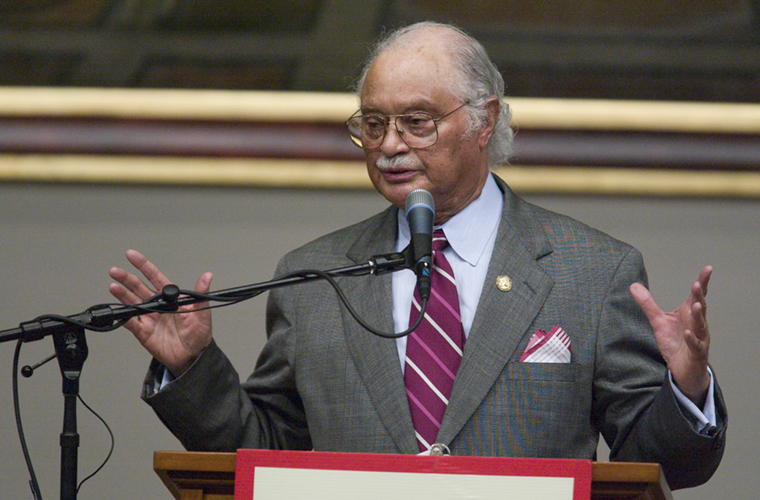

In 1950 Horace T. Ward became the first African American to challenge racially discriminatory practices at the University of Georgia (UGA). Although the all-white UGA School of Law rejected Ward’s application and a federal court subsequently upheld the university’s decision, Ward’s challenge to the university’s segregationist policies began a legal process that would eventually bear fruit in 1961. He would later become the first African American ever to serve on the federal bench in Georgia.

Horace Taliaferro Ward was born in LaGrange on July 29, 1927, the only child of Minnie Ward, who worked as a domestic. He never knew his father. Because his mother lived with the white people for whom she worked, Ward lived with his mother’s parents until he began school at age nine. Though he began school late, he was a bright and eager pupil. After he finished the fourth grade, his teacher convinced the principal that Ward should be allowed to skip the fifth grade and go directly to the sixth. He graduated valedictorian of East Depot Street High School in 1946.

After high school, Ward enrolled at Morehouse College in Atlanta and majored in political science. Upon completion of his bachelor’s degree in 1949, he enrolled at Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), earning a master’s degree in 1950. While at Atlanta University, Ward came under the influence of William Madison Boyd, chair of the political science department and president of the Georgia branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Ward had been interested in studying law ever since he first learned of A. T. Walden, one of the few Black lawyers practicing in Georgia at the time. But Ward had no interest in attending school out of state, and he knew that the state’s premier law school, located in Athens, did not admit Black students. Boyd had been searching for someone to break the color barrier at the University of Georgia, and he believed that Horace Ward had the credentials to do it. Ward agreed to apply.

On September 29, 1950, Ward formally applied to law school at UGA. The university registrar, Walter N. Danner, forwarded Ward’s application to the Board of Regents—a procedure that was not followed for white applicants. When L. R. Seibert, executive secretary of the Board of Regents, offered Ward out-of-state tuition assistance, Ward refused it and insisted that his application be judged on its merits. Despite Ward’s repeated requests for updates on the status of his application, the regents continued to stall. Finally, on June 7, 1951, Danner informed Ward by letter that his application had been denied. The university’s decision came more than nine months after Ward had filed his application.

For the next twelve months, Ward tried in vain to get university officials to give him a reason for their decision. Up to this point, university officials, including President O. C. Aderhold and University System of Georgia chancellor Harmon Caldwell, had insisted that Ward was simply “not qualified” for admission, despite his stellar academic performance at both Morehouse and Atlanta University. University officials steadfastly denied that UGA excluded Black students; the fact that no Black student had ever been admitted to the university was merely coincidental. Meanwhile, the Board of Regents decided to “modify” the admissions criteria by requiring that candidates take an entrance exam and that they get two additional letters of recommendation—one from a UGA law school alumnus and the other from the superior court judge in the area where the applicant resided. By now, Ward’s attorneys, who included Walden, Donald Hollowell, and Constance Baker Motley, were convinced that Ward would never enter the UGA’s law school except by court order. They filed suit in federal district court in Atlanta on June 23, 1952.

Ward would eventually have his day in court, but he would have to endure years of delays and legal maneuvering by the state’s attorneys. His original court date, set for October 5, 1953, was postponed indefinitely after Ward received a suspiciously timed draft notice on September 9. After serving two years in the U.S. Army (including a year in Korea), Ward came home in 1955 and immediately reactivated his lawsuit. Though attorneys for the university and the state filed several new motions for dismissal, Ward’s court date was reset for December 17, 1956, more than six years after Ward’s application to UGA’s law school.

On February 12, 1957, Judge Frank A. Hooper dismissed Ward’s lawsuit against UGA on the grounds that (1) Ward had refused to reapply to the law school under the new guidelines (which Ward’s attorneys had argued was yet another ploy to keep Ward out), and (2) that Ward’s enrollment at Northwestern University’s law school had in effect rendered moot his application to UGA. (Fearing that he would never be admitted to UGA, Ward had quietly enrolled at Northwestern in Evanston, Illinois, in the fall of 1956.) Concluding that he had already devoted too much of his life to trying to break the color barrier at UGA, Ward decided not to appeal the decision. Although Ward’s efforts were not successful, his case helped to lay the groundwork for desegregation. After completing law school at Northwestern in 1959, Ward returned to Georgia and assisted Donald Hollowell and Constance Baker Motley in their renewed efforts to desegregate UGA. On January 6, 1961, Judge William A. Bootle ordered UGA to admit two Black students, Hamilton E. Holmes and Charlayne A. Hunter, thus ending 175 years of segregation at the university.

In the early 1960s, Ward was a partner in the law firm of Hollowell, Ward, Moore, and Alexander. For nine years (1965-74) he served in the Georgia senate. The high point of his career came in 1979, when U.S president Jimmy Carter appointed him to a federal judgeship on the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, thereby making Ward the first African American ever to sit on the federal bench in Georgia. In an interesting twist of fate, Ward later presided over several cases in which UGA was the defendant. Judge Ward took senior status, reducing his workload, in 1994.

Ward was awarded an honorary law degree from UGA in 2014 because he had made “substantial contributions to our university community by delivering lectures to our students and by sharing his story with our historians,” according to UGA President Jere W. Morehead.

Ward died of natural causes near Atlanta on April 23, 2016, at the age of eighty-eight.