The Negro World (1918–1933) was the organ of Marcus Garvey‘s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the most massive African-American and Pan-African movement of all time. Garvey’s was a black nationalist movement organized around the principles of the race first, self-reliance, and nationhood. At its height in the mid-1920s, the UNIA comprised millions of members and close supporters spread over more than forty countries in the Americas, Africa, Europe, and Australia. The Negro World was a faithful reflection of all the UNIA stood for. It educated African people everywhere on the need for self-determination and racial uplift. With its international reach, it became a major recruiting tool for the organization. Like the larger movement, however, the Negro World was viewed with hostility and suspicion by European and other governments.

The Negro World began publication in 1918 in Harlem, New York, about two years after Garvey arrived in the United States from his native Jamaica. Garvey had founded the UNIA in Jamaica in 1914, and he conceived the idea of a major publication before leaving for the United States. He brought considerable experience in journalism and printing to the paper. While still a teenager, he had been a foreman printer in Jamaica, and he had published papers in Costa Rica and Panama. He had worked on possibly two papers in Jamaica and for the important Africa Times and Orient Review in London in 1913. The earliest issues of the paper were edited by Garvey and slipped free under people’s doors in Harlem. Garvey’s responsibilities in building the UNIA did not permit him to do the hands-on day-to-day work of running the paper for very long. Though he remained managing editor, he quickly initiated the paper’s policy of employing some of the best editorial brains in African America. Among these were Hubert H. Harrison (1883–1927), one of Harlem’s most respected intellectuals; W. A. Domingo, a Socialist and sometime publisher of his own Emancipator; the veteran journalist John E. Bruce (known in the newspaper world as “Bruce Grit”); William H. Ferris (1874–1941), an author and graduate of Yale and Harvard; T. Thomas Fortune (1856–1928), the “dean” of African-American journalists; and the second Mrs. Garvey, Amy Jacques Garvey (1885–1973).

Among the regular columnists, contributors, and book reviewers were important personalities in Pan-African history. These included Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950), the “father of African-American history”; the popular historian J. A. Rogers (1880–1966); and Duse Mohamed Ali (1866–1945), the editor of the London-based Africa Times and Orient Review.

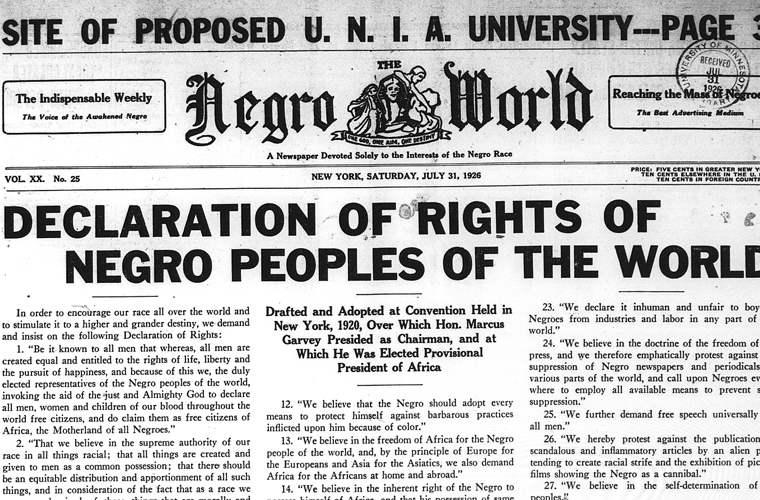

The paper was forceful in tone. “Negroes get ready,” it proclaimed from the masthead of early editions. Garvey himself wrote a bold-typed, front-page editorial for each issue. This formed the text for weekly meetings of the UNIA all over the world. The coverage of Pan-African and anticolonial news was very broad. Sections of the paper were for a time published in French and Spanish. Articles were well written and sober; there was none of the sensationalism and frivolity of the popular press. Garvey credited himself with having raised the quality of African-American journalism.

Despite its overwhelmingly political orientation, the paper also acted as a literary journal. Poems from contributors around the world appeared every week for several years. The paper boasted African America’s first regular book review section. Short stories, plays, and literary and cultural criticism appeared regularly. Major Harlem Renaissance figures such as Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960) and Eric Walrond (1898–1966) published in the Negro World.

At the same time, the paper did not neglect its role as an organ of a great movement. Proceedings of public meetings and conferences filled many pages. Weekly reports of branch meetings were faithfully recorded. Among the authors of such organizational business was Louise Little, the mother of Malcolm X.

The Negro World‘s circulation is said to have reached 200,000 in the 1920s, making it one of the largest newspapers in African America. It was undoubtedly also the most widely circulated African newspaper internationally. People coming into contact with the paper’s message in places as far apart as Dominica and Nigeria were impelled to become Garveyites, sometimes founding their own local branches of the UNIA in the process. Official circulation efforts were supplemented by itinerant seamen who, sometimes acting entirely on their own, took the paper around the world.

The United States, as well as European and other governments, waged a protracted struggle to destroy the paper. Within a year of its appearance in 1919, it was already banned in some British Caribbean territories, Trinidad and British Guiana among them. An African in Southern Rhodesia was sentenced to life in prison (the sentence later rescinded after representations to the British parliament) for importing a few copies.

The Negro World survived Garvey’s deportation from the United States in 1927 and subsequent schisms in the UNIA, and the paper remained loyal to him until its demise in 1933. Garvey published two newspapers in Jamaica, and a magazine in Jamaica and England, after his deportation from the United States. The UNIA also briefly supplemented the weekly Negro World with a Daily Negro Times in the early 1920s. However, none of Garvey’s other journalistic endeavors ever matched the power and influence of the Negro World. With its combination of wide circulation, international outreach, the excellence of editorship, and worldwide influence, the Negro World may have been the best African-American newspaper of all time.