Sarah Jane Smith Thompson Garnet is best known as the first Black female principal of a New York City public school. She was equally active in the suffrage movement. Like other Black suffragists, she pursued women’s voting rights as part of a broad vision of justice and equality for Black people. Black suffragists saw the ballot as one piece of a fight for civil rights, education, economic power, and an end to segregation and racist violence.

Garnet was born Sarah Jane Smith in Brooklyn in 1831. Her parents Sylvanus and Annie Springstead were prosperous farmers who made sure their eleven children got good educations. By age fourteen, Sarah Smith was a successful student and classroom monitor. She taught in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and then became the principal of an integrated school in Manhattan. Garnet was the first Black woman principal in the city’s public school system.

Garnet was also a prominent leader in the Black women’s club movement. She founded the Equal Suffrage League, a suffrage club for Black women, in Brooklyn in 1902. The League met in Garnet’s home or in a nearby YMCA on Carlton Avenue in Fort Greene, at the time a middle-class Black neighborhood. Black men as well as women attended many of the meetings. In 1907, the Equal Suffrage League invited Anne Cobden-Sanderson to speak. Cobden-Sanderson was the first British suffrage leader to visit the United States. The British movement would become more and more influential in the United States over the next few years.

Garnet also worked to support Ida B. Wells’s anti-lynching campaign and to end discrimination against Black teachers. She was an early member of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), going on to head its Suffrage Department. Alongside leaders like Wells, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Victoria Earle Matthews, and Mary Church Terrell, Garnet connected the women’s ballot to a broader agenda of racial uplift and equal rights.

The Equal Suffrage League and New York’s white-dominated suffrage organizations did work together. But white suffragists’ racism limited the extent of interracial cooperation. In 1910, for example, Garnet met with wealthy suffragist Alva Belmont. Belmont wanted to set up a “colored” branch of her Political Equality Association. The leaders set up a public meeting, but Black women’s interest wasn’t strong. A newspaper report of the meeting noted that white women’s suffrage speeches “did not evoke much applause.” Black women were already organized for suffrage–they did not need white women to do it for them.

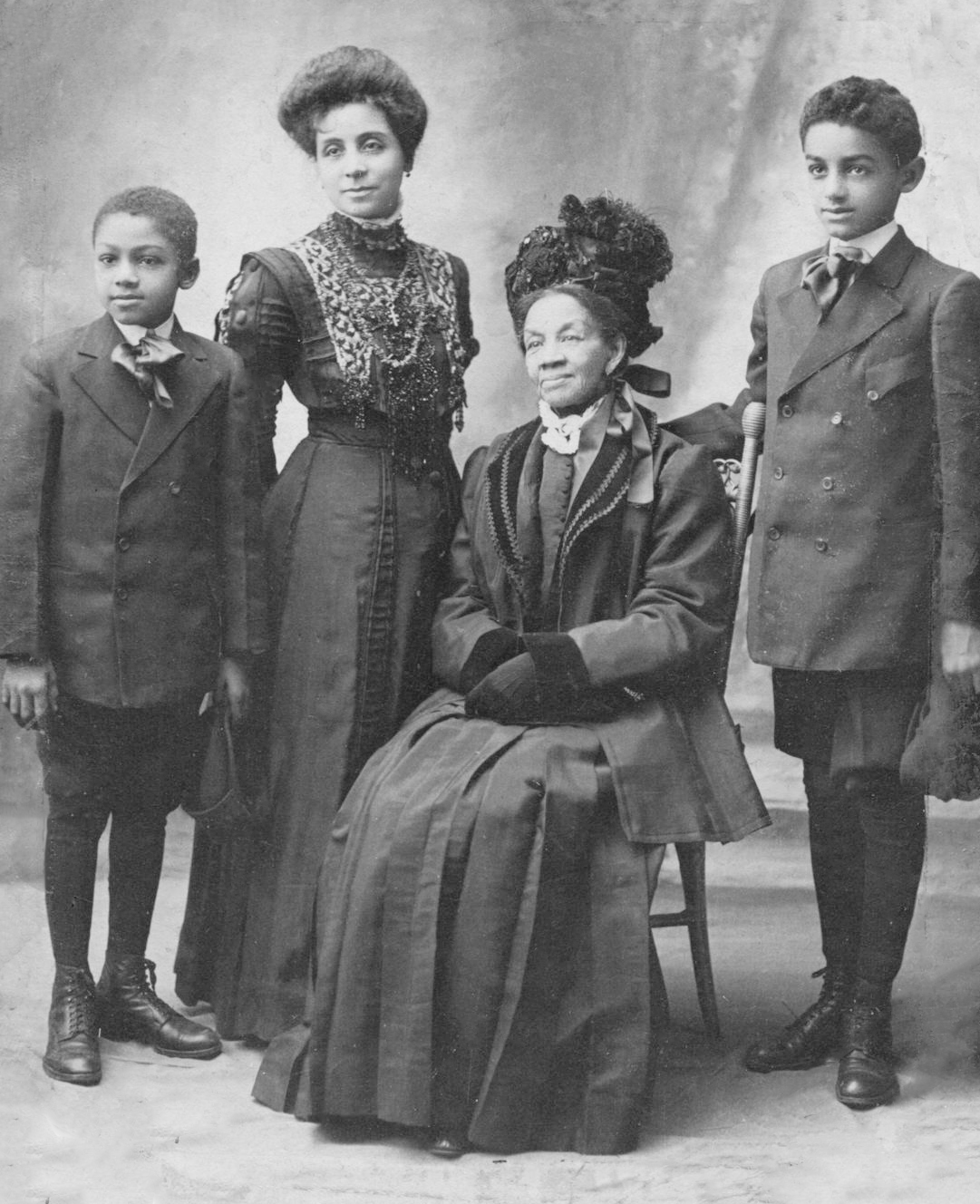

Garnet’s activism extended beyond American borders as well. In 1911, she and her sister Dr. Susan McKinney went to London for the inaugural Universal Races Congress, an early global effort to promote interracial harmony. McKinney, a fellow activist, and the first Black woman doctor to be licensed in New York presented a paper at the meeting. Garnet brought back word of the exciting progress of the suffrage movement in England.

Sarah J. Garnet married twice. In the 1850s she married James Thompson, who died in the late 1860s. (Several sources mistakenly give Thompson’s name as “Tompkins.”) The couple’s two children both died before reaching adulthood. In 1879, she wed the famous abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet. The Garnets apparently separated after a year, and Henry Highland Garnet died in 1882 in Liberia.

Garnet died in her Brooklyn home on September 17, 1911, shortly after returning from London. At her memorial service, speakers included W. E. B. Du Bois and anti-lynching activist Addie Waites Hunton. They remembered Garnet as a teacher, a champion of equal rights, a club woman, a suffragist, and a leader of the “womanhood of her race.” She is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery.

In 2019, a Brooklyn elementary school was renamed “PS9 Sarah Smith Garnet” in her honor.