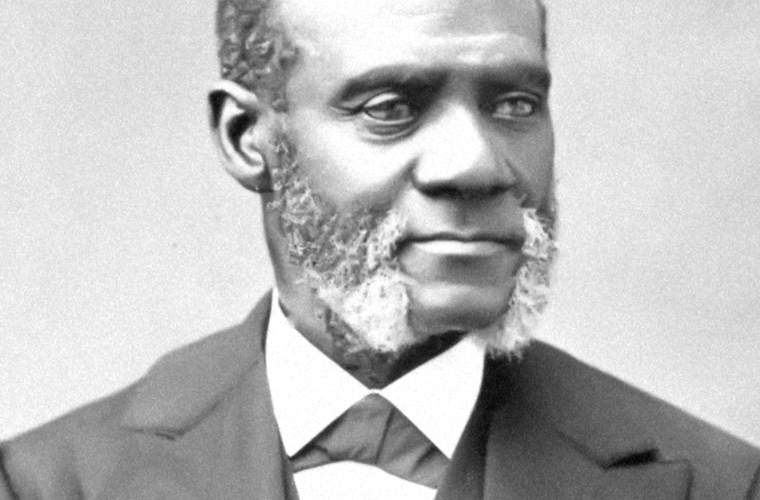

Henry Highland Garnet (1815–1882) was a leading member of the generation of black Americans who led the abolition movement away from moral suasion to political action. Garnet urged slaves to act and claim their own freedom. Garnet worked to build up black institutions and was an advocate of colonization in the 1850s and after. Garnet also devoted his life to ministry in the Presbyterian Church.

Garnet was born into slavery near New Market, Kent County, Maryland, on December 23, 1815. His father, George Trusty, was the son of a Mandingo warrior prince, taken prisoner in combat. George and Henny (Henrietta) Trusty had one other child, a girl named Mary. George had learned the trade of shoemaking. The Trusty’s owner, William Spencer, died in 1824. A few weeks later 11 members of the Trusty family received permission to attend a family funeral. They never returned. Traveling first in a covered market wagon and then on foot for several days, the family group made its way to Wilmington, Delaware. There they separated; seven went to New Jersey, and Garnet’s immediate family went to New Hope, Pennsylvania, where Garnet had his first schooling.

In 1825 the Garnets moved to New York City. There, after earnest prayer, George Trusty gave new names to the family. His wife Henny became Elizabeth, and his daughter Mary, Eliza. Although the original first names of George and Henry are unknown, the family name became Garnet. George Garnet found work as a shoemaker and also became a class leader and exhorter in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Garnet entered the African Free School in Mott Street in 1826. There he found an extraordinary group of schoolmates. They included Alexander Crummell, an Episcopal priest and a leading black intellectual, who was Garnet’s neighbor and close boyhood friend; Samuel Ringgold Ward, a celebrated abolitionist and a cousin of Garnet; James McCune Smith, the first black to earn a medical degree; Ira Aldridge, the celebrated actor; and Charles Reason, the first black college professor in the United States and long-time educator in black schools. Garnet and his classmates formed their own club, Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association, and soon had occasion to demonstrate their spirit. Garrison’s abolitionism had little mass support among whites at this time, and abolition meetings in New York City easily led to mob violence. Thus, even the school authorities feared the use of his name for a club meeting at the school. The boys retained the club’s name and moved their activities elsewhere.

As a boy, Garnet was high-spirited and quite different from the sober and quiet adult he later became. In 1828 he made two voyages to Cuba as a cabin boy, and in 1829 he worked as a cook and steward on a schooner from New York to Washington, D.C. On his return from this voyage, he learned that the family had been scattered by the threat of slave catchers. His father had escaped by leaping from the upper floor of the house at 137 Leonard Street—next door to the home of Alexander Crummell. The family of a neighboring grocer had sheltered his mother. His sister was taken but successfully maintained a claim that she had always been a resident of New York and therefore no fugitive slave. All of the family’s furniture had been stolen or destroyed. Garnet bought a large clasp knife to defend himself and wandered on Broadway with ideas of vengeance. Friends found him and sent him to hide at Jericho on Long Island.

Since Garnet had to support himself, he was bound out to Epenetus Smith of Smithtown, Long Island, as a farm worker. While he was there he was tutored by Smith’s son Samuel. In the second year there, when he was 15, Garnet injured his knee playing sports so severely that his indentures were canceled. The leg never properly healed, and he used crutches for the rest of his life. (After 13 years of suffering and illness, the leg was finally amputated at the hip in December 1840.) Garnet returned to his family, which had reestablished itself in New York. He then continued his schooling, and in 1831 he entered the newly established high school for blacks, rejoining Alexander Crummell as a fellow student.

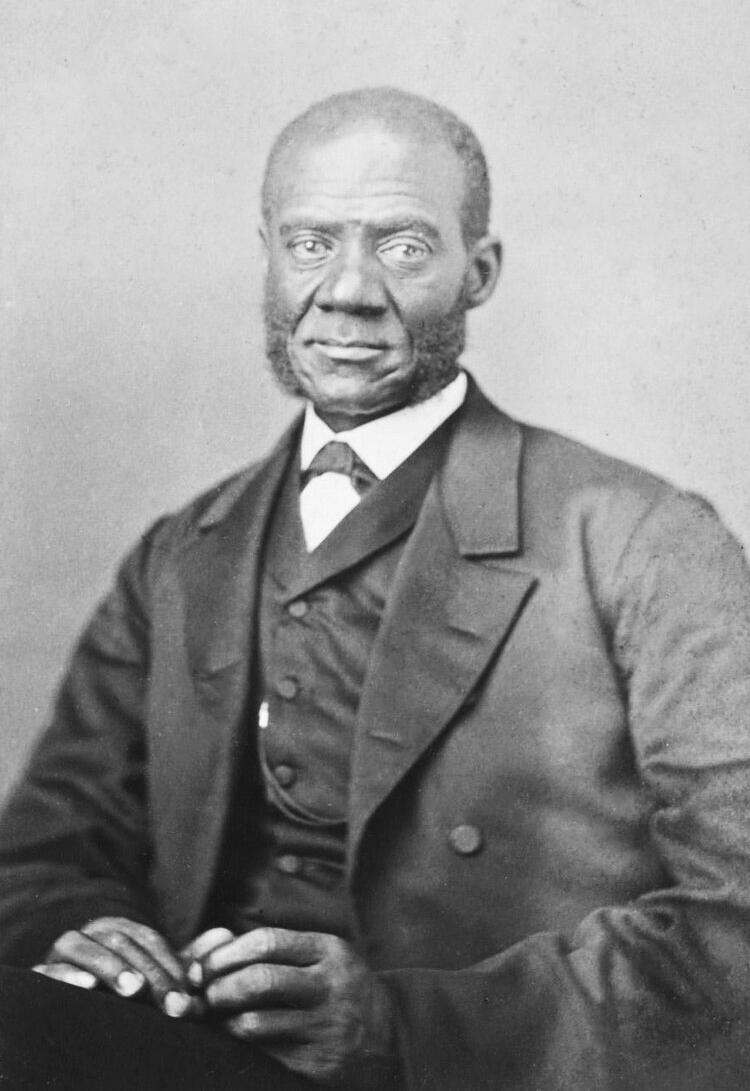

The leg injury may have sobered Garnet, who became more studious and turned his thoughts to serious consideration of religion. Sometime between 1833 and 1835, he joined the Sunday school of the First Colored Presbyterian Church, located at the corner of William and Frankfort streets. There Garnet became the protegé of the minister and noted abolitionist Theodore Sedgewick Wright, the first black graduate of Princeton’s Theological Seminary, who brought about Garnet’s conversion and then encouraged him to enter the ministry.

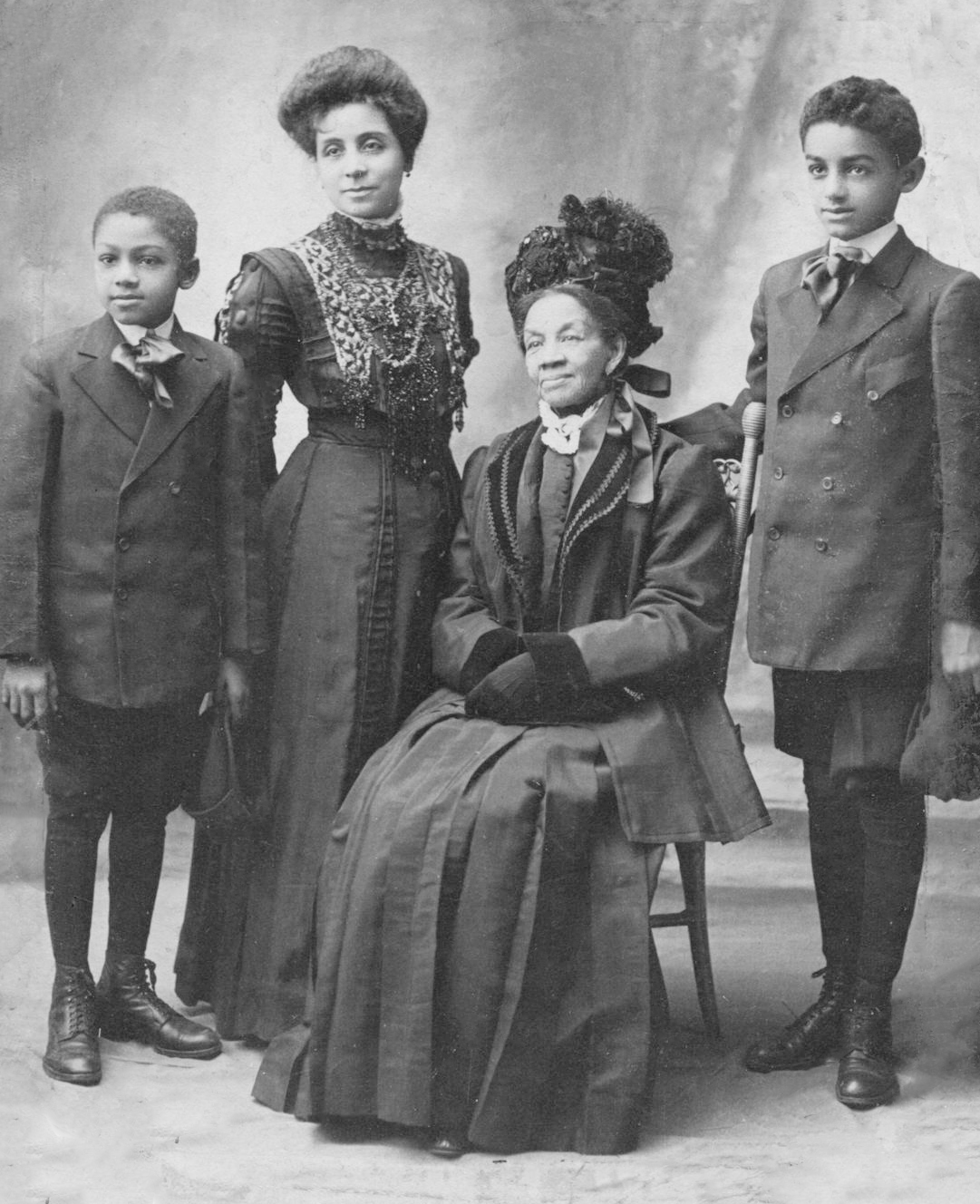

Garnet married Julia Ward Williams in 1841, the year he has ordained an elder. Williams was born in Charleston, South Carolina, but came to Boston at an early age. Williams had studied at Prudence Crandall’s school in Canterbury, Connecticut, and also at Noyes Academy. She taught school in Boston for several years and after her marriage was head of the Female Industrial School while the family lived in Jamaica. The couple had three children: James Crummell (1844–1851); Mary Highland (born c. 1845); and a second son (born 1850). There was also an adopted daughter Stella Weims, a fugitive slave. Julia Garnet died in 1870, and in about 1879 he married Susan Smith Thompkins, a noted New York teacher and school principal.

In 1835 Garnet, Alexander Crummell, and Thomas S. Sidney, classmates from New York, made the difficult journey to the newly-established Noyes Academy in Canaan, New Hampshire. Founded by abolitionists, Noyes was open to both blacks and whites and to men and women. (There Garnet met Julia Williams.) The students from New York were in New Hampshire by July 4, when they delivered fiery orations at an abolitionist meeting. A vocal minority of local townspeople was determined to close down the school and drive away the 14 blacks enrolled. In August they attached teams of oxen to the schoolhouse, dragged it away, and burned it. Garnet, Crummell, and Sidney returned to New York.

Fortunately, there was another institution that opened its doors to black students, and this time the local townspeople did not rise up physically to reject them. In early 1836 Garnet joined Crummell and Sidney at Oneida Institute in Whitesboro, New York. In May 1840 Garnet attended the meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York and delivered a well-received maiden speech. In September, he graduated from Oneida with honors and settled in Troy, New York.

Even though Garnet was not yet ordained, he had been called as minister to the newly established Liberty Street Presbyterian Church at Troy, New York. Garnet studied theology with the noted minister and abolitionist Nathaniel S. S. Beman, taught school, and worked toward the full establishment of the church whose congregation was black. In 1842 Garnet was licensed to preach and in the following year ordained a minister. He thus became the first pastor of the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church in Troy, where he remained until 1848.

Teaching and the ministry hardly filled all of Garnet’s time. He assisted in editing The National Watchman, an abolitionist paper published in Troy during the latter part of 1842, and later edited The Clarion, which combined abolitionist and religious themes. Closely interwoven with Garnet’s church work was his work in the Temperance Movement, in which he took a leading part. By 1843 he received a stipend of $100 a year from the American Home Missionary Society for his work for abolition and temperance. When the society expressed its objections to ministers engaging in politics on Sundays, Garnet withdrew his services. His work for temperance was widely recognized. In 1848 one of the two Daughters of Temperance unions in Philadelphia was named for him.

State politics also brought Garnet into prominence. There were black state conventions from 1836 to 1850. Garnet worked for the extension of black male voting rights in New York state, but a property holding qualification was imposed upon blacks. He presented several petitions to the legislature on this subject. However, state property qualification remained the law until the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.

In 1839 the Liberty Party came into existence with abolition as one of its major planks. Although its vote in the 1840 elections was minuscule, the party set its sights on the 1844 election. Garnet became an early and enthusiastic supporter of this reform party. He delivered a major address at the party’s 1842 meeting in Boston. He was also able to secure the endorsement of the revived National Convention of Colored Men, held in Albany in August 1843 for the party. Garnet gave a convincing demonstration of his oratorical powers soon afterward when he turned around a New York City meeting convened to disavow the convention’s action. Much to the organizers’ disappointment the meeting ended by endorsing the Liberty Party. The year 1844 marked a peak for the party. Then the Free Soil Party and later the Republican Party began to attract reform-minded voters. Garnet was late and unenthusiastic in supporting the Republicans.

Garnet’s turn towards activism marked his break with leading abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who rejected politics in favor of moral reform. Garnet’s impatience with Garrison’s position was expressed publicly as early as 1840 when he was one of the eight black founding members of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society which formalized the split in the ranks of abolitionists.

Just as Garnet was in the vanguard of the blacks who began to seek remedies in political action and even revolution, he also led the way in proposing emigration as a solution for the black plight in the United States as proposed by the American Colonization Society. Since 1817 most American blacks condemned the American Colonization Society and were suspicious of the society’s aims and of its creation, the nation of Liberia, which became independent in 1847. Garnet, however, was coming to favor black emigration to any area where there might be the hope of being treated justly and with dignity. Bitter personal experience soon underlined his position: in the summer of that year, he was choked, beaten, and thrown off a train in New York State.

Garnet moved from Troy to Geneva in 1848. Then in 1850, he went to Great Britain at the invitation of the Free Labor Movement, an organization opposing the use of products produced by slave labor. The following year he was joined by his family. There he remained for two and a half years, undertaking a very rigorous schedule of engagements. Both James McCune Smith and Frederick Douglass felt he was doing especially well because he was the first American black of completely African descent to appear there to speak in support of abolition. Douglass did not relax his general hostility to Garnet, however, and gave little attention to Garnet’s activities abroad.

In the latter part of 1852, the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland sent Garnet to Jamaica as a missionary. He did effective work there until a severe prolonged illness caused his doctors to order him north. In 1855 he was called to Shiloh Church on Prince Street, where he became the successor of his mentor, Theodore S. Wright. Although the support for emigration was growing in the black community, Garnet had to face sharp criticism for his position in favor of it, particularly from Frederick Douglass. Douglass commented sharply on a request for American blacks to go to Jamaica made by Garnet before his return.

Alexander Crummell, Garnet’s boyhood friend and fellow student who had established himself in Liberia after earning a degree from Cambridge University in England, endorsed the goal, as did the influential West-Indian-born educator Edward Wilmot Blyden. Garnet made a trip to England as president of the society in 1861. In conjunction with this trip, he established a civil rights breakthrough by insisting that his passport contain the word Negro. Before this time the handful of passports issued to blacks had managed to skirt the issue of whether blacks were or were not citizens of the United States by labeling the bearer with some term such as dark. Although Garnet’s and Martin Delany’s efforts at colonization at this time were running in parallel and not coordinated, the pair agreed on aims. Garnet proposed a visit to Africa to follow up on Delany’s 1859 efforts there, but the plan fell through with the outbreak of the Civil War.

With the outbreak of the war, Garnet joined other blacks in urging the formation of black units. When this goal was realized at the beginning of 1863, he traveled to recruit blacks and served as chaplain to the black troops of New York State, who were assembled on Ryker’s island for training. He led the work of charitable organizations that worked to overcome the unfavorable conditions initially facing the men due to wide-scale corruption and anti-black sentiments in the city.

In March 1864 Garnet became pastor of the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church of Washington. D.C. There he delivered a sermon in the chamber of the House of Representatives on February 12, 1865, the first black to do so, and also one of the first blacks allowed to enter the Capitol. He moved his residence to Washington and became the editor of the Southern Department of the Anglo-African. As an assignment, Garnet undertook a four-month trip to the South at the end of the war, which included a visit to his birthplace. Garnet accepted the presidency of Avery College in Pittsburgh in 1868 but returned to Shiloh Church in New York in 1870.

Crummell reported that Garnet went into a physical and mental decline in about 1876. In spite of the discouragement of his friends, Garnet actively lobbied for the position of minister to Liberia, which he obtained. Garnet preached his farewell sermon at Shiloh on November 6, 1881, and landed in Monrovia on December 28. He died on February 13, 1882.