A Defiant Voice in the Abolitionist Struggle

Shields Green, born around 1836 in the bustling port city of Charleston, South Carolina, emerged from the shadows of enslavement to become one of the most resolute figures in the American fight against slavery. Often referring to himself with a touch of regal defiance as “Emperor,” Green embodied the unyielding spirit of countless African Americans who risked everything for freedom. His life, though tragically brief and marked by profound loss, intersected with the era’s most fiery abolitionists, culminating in his bold participation in John Brown’s audacious 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry. Green’s story is not just one of personal courage but a poignant reminder of the Black freedom fighters whose sacrifices fueled the flames of resistance leading to the Civil War.

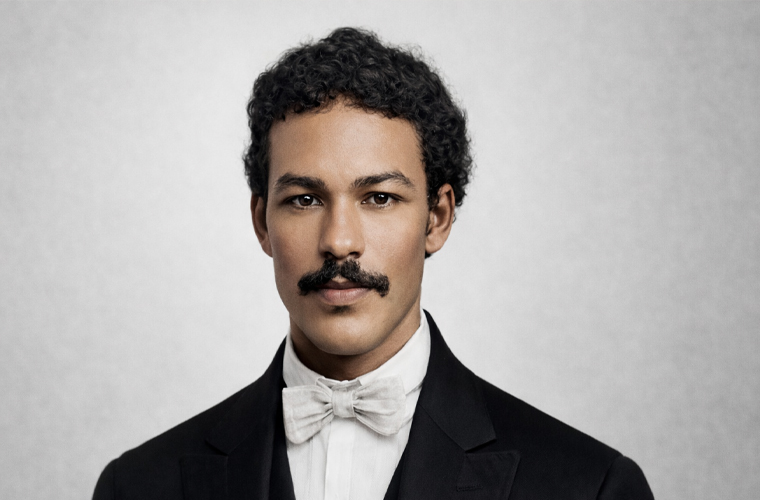

Green’s early years were shrouded in the brutal machinery of Southern slavery, where he was born into a world that viewed Black lives as chattel. Charleston, a hub of the domestic slave trade, was a place of relentless exploitation, and Green likely toiled in urban roles such as a waiter or laborer from a young age. Fragmentary accounts suggest he was a widower by the time of his escape, having endured the heartbreak of seeing his young son sold away—a common cruelty that hardened his resolve against the institution. Little is definitively known about his parents or precise birthdate, with estimates ranging from 1825 to 1836, reflecting the deliberate erasure of enslaved people’s histories. What is clear is that Green was described by contemporaries as a man of small stature but sharp intellect, with dark skin, short curly hair, and a speech impediment that lent his words a distinctive, halting cadence—traits that did not diminish his commanding presence.

At around age 20, in the mid-1850s, Green seized his chance for liberty. Disguising himself as a free Black man, he stowed away in the cargo hold of a northbound ship, enduring the perilous Atlantic voyage hidden among crates and barrels. This audacious escape via the maritime Underground Railroad—far riskier than overland routes—landed him in the free North, where he navigated a landscape still fraught with danger from slave catchers and discriminatory laws. After brief stints in ports like New York and possibly Pittsburgh or Harrisburg, Green found refuge in Rochester, New York, a vibrant epicenter of abolitionism often called the “Flower City” for its radical bloom of anti-slavery activism.

Forging Alliances in Rochester: A Barber, a Fighter, and a Friend to Douglass

Rochester welcomed Green into a tight-knit community of free African Americans and escaped slaves, where he quickly established himself as a journeyman barber—a trade that allowed him modest independence while sharpening his skills in observation and conversation. For nearly two years starting in 1857, he lived in the home of Frederick Douglass, the era’s most eloquent ex-slave and abolitionist luminary. Douglass, who had himself fled Maryland’s Eastern Shore, saw in the young Green a kindred spirit: intelligent, self-possessed, and fiercely committed to the cause, despite his limited formal education and the “singularly broken” quality of his speech. Under Douglass’s roof, Green absorbed the intellectual fervor of the household, attending lectures, debating strategies for emancipation, and contributing to the underground network that funneled fugitives northward.

It was here, amid Rochester’s abolitionist circles, that Green first crossed paths with John Brown, the grizzled Kansas warrior whose unapologetic militancy resonated with Green’s own simmering rage. Brown, plotting his grand scheme to arm a slave uprising, confided in Douglass and, by extension, Green. The young barber’s exposure to these ideas transformed him from a survivor into a strategist, honing his resolve in a city that had sheltered radicals like the women of the Seneca Falls Convention and Underground Railroad operatives who smuggled hundreds to Canada.

The Call to Arms: Joining John Brown’s Raid

By the summer of 1859, the air crackled with the inevitability of conflict. John Brown, undeterred by failures in “Bleeding Kansas,” assembled a diverse band of 22 raiders—five of them Black, including Green—to strike at the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). The plan was audacious: seize thousands of rifles and pikes, distribute them to enslaved people in the surrounding Blue Ridge Mountains, and ignite a widespread rebellion that would ripple southward, dismantling the slave system from within.

Green’s commitment crystallized during a clandestine meeting on August 21, 1859, in a Pennsylvania stone quarry near Chambersburg. Accompanying Douglass, Green listened as Brown outlined the perilous mission. When Douglass, wary of its suicidal odds, declined to join and urged Green to return to the safety of Rochester, the young man paused only briefly. With unwavering conviction, he replied, “I b’l’eve I’ll go wid de old man.” It was a declaration of loyalty not just to Brown but to the dream of universal freedom—a moment Douglass later immortalized as emblematic of Green’s unyielding bravery. Green joined the raiders at a secluded Maryland farm, where they trained in secrecy, their numbers swelling with idealism and dread.

The Raid: Fury at Harpers Ferry

On the moonlit night of October 16, 1859, Brown’s band descended on Harpers Ferry. Initial success was swift: they captured the armory, the rifle works, and a passenger train, taking hostages, including the armory’s night watchman. Green, at just 23, the youngest of the raiders, proved a whirlwind of action. Stationed at the arsenal gate, he avenged the death of fellow Black raider Dangerfield Newby—killed earlier in the chaos—by fatally shooting Newby’s killer, a local militia captain. Throughout the night, Green guarded terrified hostages in the fire engine house, his rifle barking defiantly as federal forces closed in. Eyewitnesses marveled at his composure; one hostage recalled Green snapping, “Shut up!” to a complaining captive, while another noted how he nearly shot the future Confederate commander Robert E. Lee but held fire on Brown’s orders.

Yet the raid unraveled by dawn. Local militias and U.S. Marines under Colonel Lee surrounded the raiders, cutting off escape routes and quelling any hope of slave uprising—enslaved people in the area, terrorized by patrols, did not rise as planned. Brown and his men, including Green, barricaded themselves in the engine house. Green, unwounded amid the gunfire, refused an offer to flee with survivor Osborne Anderson, choosing instead to stand with “the old man” to the end. Captured on October 18, he was one of seven raiders seized alive, his face bloodied but spirit unbroken.

Trial, Conviction, and a Martyr’s End

The aftermath was swift and merciless. Transferred to Charles Town (now Charlestown, West Virginia), Green faced a biased court in a slaveholding state. Tried from November 3 to 5 alongside John Copeland, another Black raider, he was charged with murder and treason for inciting slave insurrection. (The treason count was controversially dropped, citing the Dred Scott decision that deemed Black people non-citizens.) The prosecutor, Hugh Hunter, unleashed racist vitriol, painting Green as a savage driven by base instincts. His defense attorney, the eloquent Bostonian George Sennott, mounted a spirited but futile argument, decrying the trial as a “farce.”

Green, true to his stoic nature, did not take the stand. He sat through the proceedings with a “stolid” demeanor, his dark eyes betraying no fear. Convicted on November 10, he was sentenced to hang, responding with eerie calm: when asked if he had regrets, he replied simply, “No, it was for my people.” On December 16, 1859, before a crowd of 1,600 gawkers—including Southern elites treating it as a spectacle—Green ascended the scaffold with Copeland. He prayed fervently, bid farewell without emotion, and dropped through the trapdoor at age 23. His body was hastily buried in a potter’s field but later exhumed by medical students for dissection, a final indignity; no family claimed his remains, and his grave remains lost.

Legacy: Echoes of Defiance in the March to War

Green’s execution, coming just two weeks after Brown’s own on December 2, electrified the nation. Northern abolitionists hailed him as a hero, while Southern fire-eaters decried the raid as proof of Black “insurrectionary” threats. Frederick Douglass, in a heartfelt eulogy, equated Green with rebels like Nat Turner and Denmark Vesey, insisting, “If a monument should be erected to the memory of John Brown… the form and name of Shields Green should have a conspicuous place on it.” The events at Harpers Ferry indeed proved a spark: they radicalized public opinion, emboldening the Republican Party and deepening the North-South chasm that erupted into the Civil War in 1861.

Today, Green’s legacy endures beyond the raid’s shadow. He is commemorated on a cenotaph in Oberlin, Ohio—erected in 1865 for Black Civil War soldiers but later inscribed for Harpers Ferry martyrs—and featured in modern works like the 2020 film *Emperor* and the Hulu series *The Good Lord Bird*. Louis A. DeCaro’s 2020 biography, *The Untold Story of Shields Green*, resurrects his “most mysterious” life, underscoring how his illiteracy, dark complexion, and status as a Black participant marginalized his story amid white-centric narratives. In an age still grappling with racial injustice, Shields “Emperor” Green stands as a testament to the profound bravery of those who, facing certain death, chose the perilous path of liberation—for themselves, their kin, and generations unborn. His quiet thunder reminds us that true emancipation demands not just words, but the willingness to “go wid de old man” into the fray.