The 54th Massachusetts Infantry was the first Northern black volunteer regiment enlisted to fight in the Civil War. Its accomplished combat record led to the general recruitment of African-Americans as soldiers. They ultimately comprised ten percent of Union Army and Navy. The Fifty-fourth’s successful campaign for equal pay also signaled a move toward racial justice in the military.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, and as the demand for Northern recruits outgrew the supply, President Abraham Lincoln agreed to enroll African-Americans in the Union army. At the start of 1863, Massachusetts’ abolitionist governor John A. Andrew received the War Department’s consent to form a regiment of free Northern blacks. Prominent abolitionist Robert Gould Shaw, who at the time was 25, accepted the position of colonel of the Fifty-fourth, believing that the regiment presented an opportunity to vindicate anti-slavery ideas. By May of 1863, 1,007 black men had enlisted in the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts.

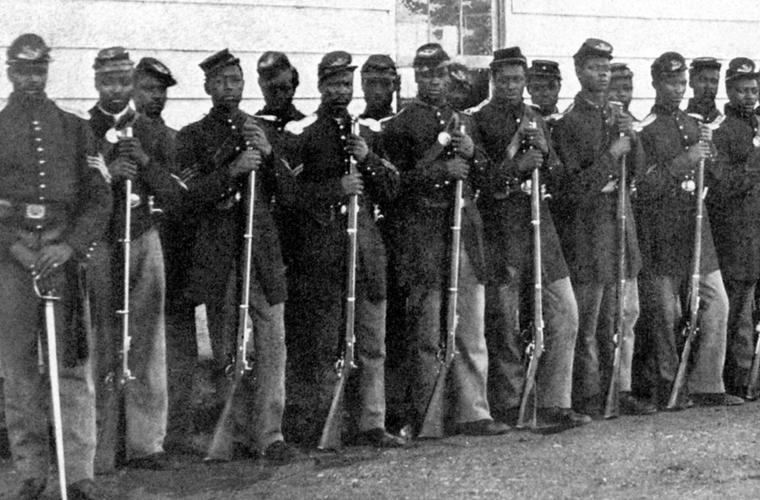

Typically, individual states recruited and trained local Civil War regiments which then joined the federal forces. In the Fifty-fourth, however, only 113 men (13%) hailed from Massachusetts. The new regiment represented a broad geographical spectrum, including soldiers from 15 Northern states, four border states, five Confederate states, Canada, and the West Indies. At least 30 were former slaves. In addition to the 1,007 black infantrymen, 37 white officers served in the regiment. While African-Americans were not permitted to serve as officers, all the sergeants and corporals were black, providing a crucial link between the enlisted men and their officers.

Colonel Shaw received his orders in May; the Fifty-fourth was to sail to Beaufort, South Carolina. After an emotional march on Boston Common on May 28, 1863, the Fifty-fourth sailed south. Assaulting James Island, the Fifty-fourth soon distinguished itself in combat. Shortly thereafter, Shaw led the renewed attack on the Confederate stronghold Battery Wagner, outside of Charleston, South Carolina. On the evening of July 18, the Fifty-fourth led a bayonet assault across a three-quarter-mile stretch of open beach. Fort Wagner, as it would generally be known, was the Fifty-fourth’s most costly and famed battle. At least 74 enlisted men and three officers, including Shaw, died in combat, and it was immediately celebrated within the Union as a heroic defeat. Following Wagner, the Fifty-fourth fought in the Battle of Olustee, the Battle of Honey Hill, and the Battle of Boykin’s Mill.

Although the Fifty-fourth demonstrated great skill and courage, the War Department did not yet recognize the equality of the African-American soldiers. Although promised 13 dollars a month, the Fifty-fourth was paid only ten, and the army expected the men to purchase their own uniforms. In protest, the men fought for 18 months for no pay whatsoever. Finally, after several appeals to the Attorney General, the Secretary of War, and the President, in July of 1864, Congress granted the Fifty-fourth their full salary, retroactive to the time of enlistment.

The regiment’s survivors were discharged on September 1, 1865, and almost immediately the black community of Boston sought to erect a memorial to the Fifty-fourth. Renowned American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens completed the memorial in 1897, and it was unveiled outside of the state house in a Memorial Day ceremony. Saint-Gaudens was initially commissioned to create an equestrian statue of Shaw alone, but Shaw’s family insisted that the Colonel is portrayed with his men. Ultimately, with Shaw on horseback, 23 black marching infantrymen were detailed in Saint-Gaudens’ bronze bas-relief. The names of the five white officers killed in battle were inscribed on the back of the monument, but it was not until 1981 that the names of the fallen black soldiers were added.

In 1989, Tri-Star Pictures released the Academy Award-winning film Glory, based on the history of the Fifty-fourth and the Fort Wagner attack. While Glory succeeded in stimulating popular discussion about the regiment and perceptions of blacks in the military, the movie also perpetuated the legacy of historical invisibility for these soldiers. While Robert Gould Shaw is portrayed realistically, every black soldier is fictional, the film ignoring such notable figures as William H. Carney, the first African-American recipient of the Medal of Honor. Nonetheless, the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts continues to be a prism through which racial conflict, fraternity, and heroism are viewed in America.