In 1713, Queen Anne of England and King Philip V of Spain signed the Treaty of Utrecht formalizing the end of Great Britain’s involvement in the War of the Spanish Succession. Under the Treaty, Spain gave Great Britain the asiento—a license to conduct the slave trade in the Spanish colonies in the New World. The contract went to the South Sea Company, which had been granted a trade monopoly with Spanish colonies of South America in exchange for converting government debt into company shares.

An intensive propaganda campaign encouraging investors to buy shares in the South Sea Company promoted the promise of the South Sea trade. “Speculators in the slave trade thought that this asset could only go up in value given that the Atlantic economy was centrally dependent on slave labor, and bought South Sea stock on the basis of this barbaric confidence,” historian Sean Moore writes. In 1711, John Morphew, a prolific distributor of political pamphlets and periodicals, published A True Account of the Design, and Advantages of the South-Sea Trade, which foresaw that the “Trade of such Places as we shall Seize and Plant, will, by Degrees . . . open such a Vein of Riches, will return such Wealth, as, in few years, will make us more than sufficient Amends for the vast Expences [sic].” Morphew’s other publications included View of the Coasts, Country, & Islands within the Limits of the South-Sea Company by Herman Moll. Moll’s book, with an accompanying map, provided readers with an overview of the history, geography, and opportunities for trade in the area. Richard Mount, the stationer to the South Sea Company, furnished further details on the possibilities for trade-in An Essay on the Nature and Methods of Carrying on a Trade to the South-Sea written in 1712 by Robert Allen.

Trade of such Places as we shall Seize and Plant, will, by Degrees . . . open such a Vein of Riches, will return such Wealth, as, in few Years, will make us more than sufficient Amends for the vast Expences.

Parliament favored the formation of the South Sea Company with its potential to increase England’s influence in South America and broaden the reach of the British Empire—noted in A True Account as “beneficial to the said Corporation, and to the whole British nation.” The British were now assuming the place of the French, who had been granted the asiento from 1701 to 1713. “The South Sea Company’s factories marked the first incorporation of subjects of the British monarch within the borders of the broader Spanish empire as important agents of trade,” Adrian Finucane writes in The Temptations of Trade: Britain, Spain, and the Struggle for Empire.

Under the treaty, the contract called for the transport of 4,800 enslaved laborers from Africa annually for a period of 30 years to Spanish colonial sites in the New World including Cartagena, Buenos Aires, Veracruz, Havana, Caracas, Portobello, Panama, Santiago de Cuba, and additional trade ports. Africans constituted a significant workforce in Spanish holdings in the Americas that included numerous gold and silver mines. The treaty also permitted the passage of one ship per year to Portobello for the trade fair. The British brought with them linen, pewter, tin, pepper, amber, woolen, and silk hose, and other goods of interest to the Spanish living in the Americas.

The company worked with the Royal African Company (the English royal chartered company) as well as independent traders. The license required the South Sea Company to pay duties on the agreed-upon contract of 4,800 slaves a year whether the quota was reached or not. As the failure to meet the quota and required payment of duties could severely affect profits, the company had to rely on independent traders to make up the difference.

On the long, grueling passage from Africa, captives suffered in close quarters and from exposure to disease that ran rampant. Ships from Africa first arrived in Jamaica or in some cases in Barbados, where the South Sea Company conducted administrative operations of the slave trade. In Jamaica, the company engaged in the dehumanizing practice of branding their captives with an “A.” The brand enabled the South Sea Company to identify Africans who may have been transported by trade interlopers. “The A tagged African people not only as of the property of the South Sea Company but also as property in the eyes of the company and all others engaged in such commerce,” Gregory O’Malley writes in Final Passages.

From the entry points, the South Sea Company transported healthy captives to main Spanish ports and from there to further settlements inland. Less healthy individuals were sent to undeveloped areas or sold to traders locally. Many women and girls endured exploitation as sex workers. “The company’s handling and sorting of people in Jamaica continued to convey to African migrants their captors’ dehumanized view of them,” O’Malley writes. “Fear, anger, and sadness were commonplace, as the meaning of traders’ choices were imagined or became known through conversations with experienced slaves working the waterfronts or holding pens.”

British agents—or factors, as they were known—conducted their affairs in factories or trading centers that contained warehouses where captives and provisions were housed. At a given trading site, agents, including a surgeon and an accountant, administered the transport of slaves into ports as well as interior parts of the colonies. The directors of the South Sea Company back in London kept in contact with factors regarding the business of the company as well as the order and rule of their place of residence in the New World, where they were adjusting to a different climate, foreign languages, and diverse cultures.

Some in England had voiced opinions against entering the slave trade not on moral grounds, but rather on the basis of the financial risks associated with the inability of the South Sea Company and its agents to carry out their work. The directors of the company had little experience in the slave trade and had to draw on the expertise of established British traders in the Caribbean. They also contended with English, French, and Dutch interlopers, who repeatedly violated the asiento contract. Further, the Spanish were not universally in favor of allowing a former enemy power into their territories and had concerns about losing a monopoly on trade in the Spanish colonies. As such, they were interested in keeping the population of British agents relatively small in order to mitigate any political or religious influence they might have.

While terms of the asiento required that South Sea Company provide five-year accounts, the company routinely evaded this request in order to cover up its practices of illicit trading that included the smuggling of contraband. Such practices were referenced in An Address to the Proprietors of the South-Sea Capital containing A Discovery of the Illicit Trade and other publications. “The cost of compliance was too high; the benefits of cheating substantial,” Salvador Carmona, Rafael Donoso, and Stephen P. Walker write in “Accounting and International Relations: Britain, Spain and the Asiento Treaty.” “As had been the case with previous Assientists, legitimate trading under the Asiento was soon discovered by the [South Sea Company] to be less remunerative than expected.”

After 1720, when the overinflated value of the South Sea Company stock dramatically rose and fell, the company maintained its involvement in the Spanish American colonies. The company would continue to experience the complexities of carrying out the slave trade with a foreign power and the conflicting and competing interests of independent traders, local South American authorities, and national governments. The contract itself was disrupted during conflicts from 1718 to 1720 (War of Quadruple Alliance), 1727 to 1729 (Anglo-Spanish War), and 1739 to 1748 (War of Jenkins Ear), adding to the heightened tensions between the two countries. In 1750, the asiento granted to Great Britain by Spain ended.

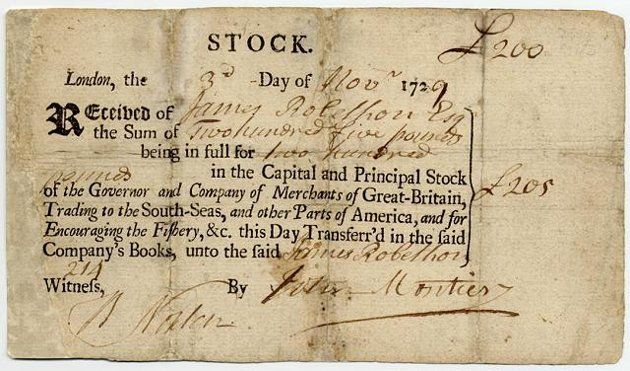

At the start, however, as Finucane notes, “The British saw an enticing opportunity to expand their own trade in slaves and manufactured goods and to exercise their considerable naval power; long before the moral debates about abolition became widespread, this seemed simply another opportunity for financial gain.” The debt-equity scheme and stock certificates of the South Sea Company counted on a human asset-that of labor carried out by enslaved persons.