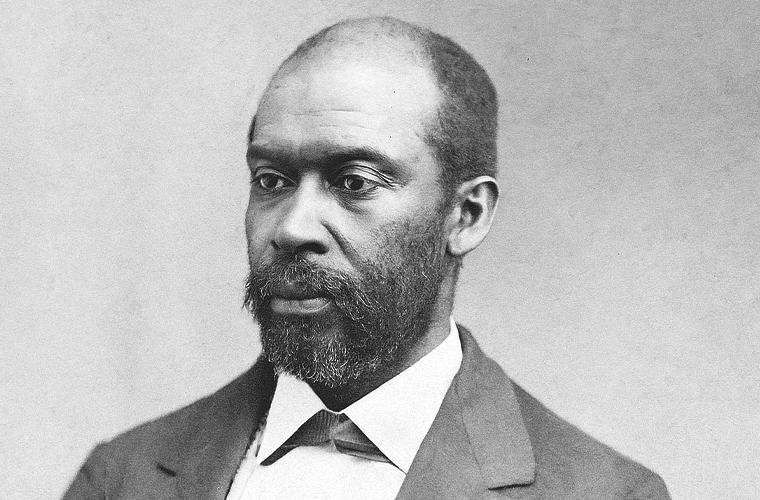

Thomas Morris Chester, born in 1834 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, emerged as a trailblazer in American journalism and civil rights, becoming the first African American war correspondent for a major daily newspaper, the Philadelphia Press. The son of an escaped slave from Baltimore and a local oyster salesman, Chester rose to prominence as one of Harrisburg’s most celebrated 19th-century African American figures. His life was marked by a relentless pursuit of education, equality, and justice, set against the backdrop of a deeply divided nation. In his youth, Chester’s passion for learning and advocacy took him to Liberia, where he immersed himself in the African colonization movement, a concept he came to champion. There, he honed his skills as a journalist, serving as editor of the Star of Liberia newspaper, and took on leadership roles in education as a school administrator. These experiences abroad shaped his worldview, instilling a sense of purpose that would define his contributions during and after the American Civil War.

When the Civil War erupted, Chester returned to the United States and threw himself into the fight for freedom. He played a pivotal role as a recruiter, rallying Black men from Pennsylvania to join the famed 54th and 55th Massachusetts Regiments, which gained renown for their courage, notably at the Battle of Fort Wagner. Chester’s efforts extended to raising federal United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments from his home state, helping to bolster the Union’s forces with African American soldiers. In 1863, during the Gettysburg campaign, Chester reportedly led two companies of Black volunteers for local defense, a historic moment documented by the Harrisburg Telegraph. This marked the first instance of Pennsylvania arming African American men, a significant milestone in the state’s Civil War history.

From August 1864 until the war’s end in 1865, Chester broke new ground as a war correspondent for the Philadelphia Press. Embedded with the Army of the Potomac, he chronicled the Union’s campaign, including the pivotal capture of Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. As the first Black reporter for a major Northern daily newspaper, Chester’s dispatches provided a unique perspective on the war, amplifying the contributions and struggles of African American soldiers and civilians alike. His work not only informed the public but also challenged the racial prejudices of the era, paving the way for future Black journalists.

After the war, Chester’s legacy continued to grow. In 1865, Pennsylvania became the only state to formally honor its African American Union troops, and Chester was chosen as the grand marshal for their celebratory parade in Harrisburg. This role underscored his stature as a respected leader within both the Black community and the broader public.

Seeking further education and opportunity, Chester traveled to England to study law, a testament to his intellectual ambition. Upon returning to the United States, he settled in Louisiana, where he held several prominent positions, including collector of customs, brigadier general of the state militia, and superintendent of schools. These roles reflected his commitment to public service and education, as well as his ability to navigate the complex racial and political landscape of Reconstruction-era Louisiana.

In 1892, Chester’s health declined, prompting his return to Harrisburg. He spent his final days in his mother’s home at 305 Chestnut Street, where he passed away. He was laid to rest in Penbrook’s Lincoln Cemetery, leaving behind a legacy of resilience and achievement. Chester’s life, marked by his roles as a journalist, recruiter, educator, and advocate, stands as a testament to the power of determination in the face of systemic barriers. His contributions to journalism and the fight for equality continue to resonate, cementing his place as a pioneering figure in American history.