The Washington Senators last won Major League Baseball’s World Series in 1924 against the New York Giants, four games to three. They went back to the championship round in 1933 but lost to New York, this time in five games.

But Washington’s last World Series team was the 1948 Homestead Grays, who defeated the Birmingham Black Barons, four games to one, to cap perhaps the most dominant stretch of baseball in American history.

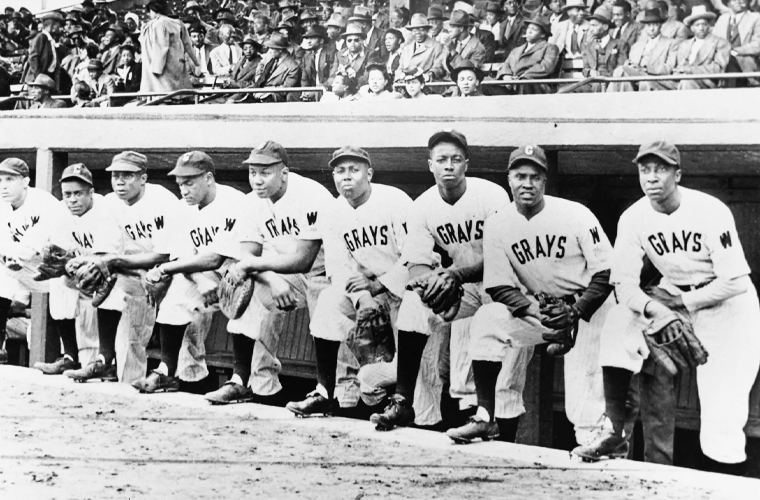

The Grays, who called both Western Pennsylvania and the District home, won nine straight Negro National League pennants from 1937 to 1945 and 10 pennants in 12 seasons from 1937 to 1948, considered a greater feat than winning a World Series because the championship matchups were not always an annual event. The 1948 series was the last one played, and while the circuit was waning, the talent remained imposing. The Grays started Hall of Famer Buck Leonard at first base. The Barons started a 17-year-old Willie Mays in center field.

With the Washington Redskins using Griffith Stadium to host the Pittsburgh Steelers, the teams met for Game 1, a 3-2 win for Homestead, in Kansas City, Mo., then split Games 2 and 3 at the Barons’ home park in Birmingham.

The Redskins were hosting the New York Giants again at Griffith Stadium, so the Grays and Barons stayed on the road, this time meeting in New Orleans. But the Grays didn’t need home-field advantage. They mopped up the Barons, 14-1, then returned to Birmingham for the decisive Game 5, a 10-6 Grays win that took 10 innings. Homestead scored four runs in the 10th to break open a 6-6 tie.

The District hasn’t hosted a World Series game since 1945, when the Cleveland Buckeyes defeated the Grays in Game 3 at Griffith Stadium, 4-0. The city hasn’t hosted a World Series victory since 1944′s decisive Game 5: Homestead Grays 4, Birmingham Black Barons 2.

While Washington’s MLB legacy is average at best — the three franchises to play in the District have a combined .465 winning percentage — the city’s baseball fans can turn to the Grays’ legacy: three World Series titles and 12 inductees to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including Leonard, Josh Gibson (known in baseball lore as the “Black Babe Ruth”) and James “Cool Papa” Bell.

And while mostly white crowds endured the jeer, “First in war, first in peace, last in the American League” as the first iteration of the Senators posted 41 losing seasons in the 60 years before the team moved to Minnesota, mostly black crowds rooted on a consistent winner at Griffith Stadium.

The Grays played a fast style of baseball: lots of balls in play and lots of stolen bases. Gibson batting from the right side of the plate and Leonard from the left side made for the “most feared batting twosome in Negro Baseball,” as Leonard’s Hall of Fame plaque reads.

“We played a different kind of baseball than the white teams,” Bell told biographer Shaun McCormack in the book “Cool Papa Bell.”

“We played tricky baseball. We did things they didn’t expect. We’d bunt and run in the first inning. Then when they would come in for a bunt, we’d hit away. We always crossed them up.”

By 1940, the Grays adopted Washington as their “home away from home” and in subsequent years played more games in the District than at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. In the mid-1940s, with the Senators mostly middling, the Grays were in their prime: They won 76 percent of their games in 1943 and boasted a roster with five Hall of Famers. They batted .330 as a team with a .458 slugging percentage, according to the database at Seamheads.com, both tops in the Negro National League.

And games at Griffith Stadium were a tremendous draw for Washington’s African American fans. Griffith Stadium was practically in the heart of the black community and next to the campus of Howard University. Surrounding the ballpark was one of the city’s middle class and upper middle class black neighborhoods, home to government workers, local business owners and university professors, said Brad Snyder, a law professor at Georgetown University and author of “Beyond the Shadow of the Senators,” a history of the Grays and Negro baseball.

“It was D.C.’s black social scene,” he said in an interview, “and the ballpark is the middle of that social scene.”

“The Homestead Grays were looked at as a spectacular team,” said Ted Knorr, founder of the Society for American Baseball Research’s semiannual Negro League Research Conference. “This was the team, with Gibson and Leonard and their two personalities, in the Negro National League.”

The Grays’ crowds were exceptional, too. Tight government controls on gasoline during World War II made getting out of the city almost impossible, Snyder said, so local residents flocked to the ballpark for summer diversions. Washington was a stop on major railways, while Pittsburgh was further west. There was no point, Snyder said, for the team to go back to Forbes Field.

But by 1948, things had changed. Homestead started four players at least 35 years-old; the lineup’s average age was 31. The Barons started seven players 30 or younger. And that series also marked the final days of the Negro Leagues. Jackie Robinson had joined the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ minor league team, in 1946. He broke the major league color barrier in 1947.

By 1948, seven black players were in the major leagues and more were in the minors. Alongside accounts of the Negro World Series games, black newspapers published stats for Robinson, Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella and Cleveland Indians outfielder Larry Doby with equal fervor.

The Negro National League shut down after the 1948 World Series. The Negro American League continued on an informal basis into the 1960s, but its final season as a major league, one comparable in talent to major league baseball, probably was the year of Washington’s last championship.