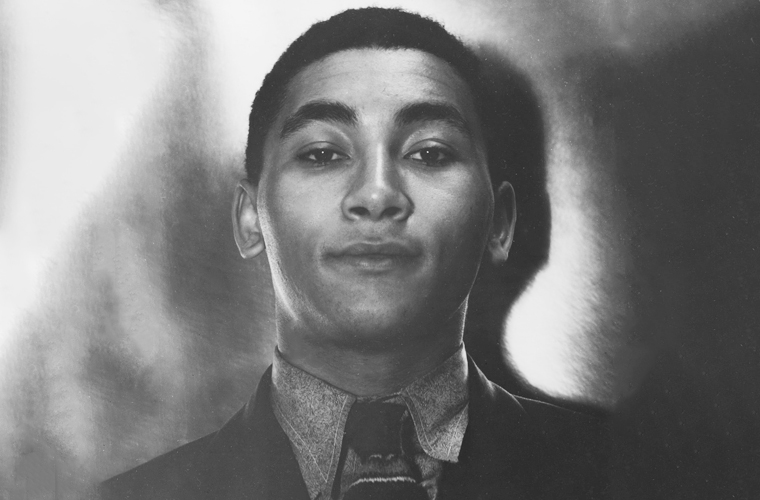

Angelo Herndon was a young African-American labor organizer who became famous for his arrest and conviction of insurrection in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1932. His case sparked a national and international campaign for his freedom, and challenged the racial and class oppression of the Jim Crow South.

Herndon was born in 1913 in Wyoming, Ohio, into a poor family. He left school at the age of 14 and worked in the coal mines of Kentucky and Alabama. There he encountered the Communist Party, which advocated for racial equality and workers’ rights. He joined the party in 1930 and became an active organizer for the Unemployed Councils, a group affiliated with the Communists.

In 1931, he moved to Atlanta, where he continued his work among the black and white workers who suffered from the effects of the Great Depression. On June 30, 1932, he helped lead a demonstration of nearly 1,000 unemployed workers at the federal courthouse, demanding relief payments that had been suspended. The protest alarmed the local authorities, who feared that it threatened the social order and racial segregation of the city. On July 11, Herndon was arrested by two detectives as he checked his mail at the post office. His hotel room was searched, and Communist literature was found. He was charged with attempting to incite insurrection, a crime punishable by death in Georgia. The prosecution based its case on Herndon’s possession of the Communist materials, which they claimed showed his intent to overthrow the government and incite a race war.

Herndon was defended by the International Labor Defense, the legal arm of the Communist Party, which hired two young lawyers, Benjamin J. Davis Jr. and John H. Geer. They argued that Herndon’s arrest violated his constitutional rights of free speech and assembly, and that he was a victim of political persecution and racial discrimination. They also presented evidence that Herndon had not advocated violence or insurrection, but rather peaceful protest and social change. The trial lasted for six days in October 1932, and attracted national attention. The jury, composed of twelve white men, deliberated for less than an hour before finding Herndon guilty and sentencing him to 18 to 20 years in prison. Herndon’s lawyers appealed the verdict, and his case went through a series of appeals that reached the U.S. Supreme Court twice.

The first time, in 1935, the Supreme Court reversed Herndon’s conviction on technical grounds, ruling that the Georgia insurrection law was vague and ambiguous. The case was remanded to the Georgia Supreme Court, which upheld the conviction again. The second time, in 1937, the Supreme Court overturned Herndon’s conviction on constitutional grounds, ruling that the Georgia insurrection law violated the First Amendment rights of free speech and assembly.

Herndon was finally released from prison in April 1937, after spending almost five years behind bars. His case had become a cause célèbre for civil rights activists, labor unions, intellectuals, artists, and celebrities who rallied for his freedom. His case also exposed the injustices and inequalities of the Southern legal system, and inspired other black radicals to challenge racism and capitalism.

Herndon wrote a memoir of his life and trial, titled Let Me Live, which was published in 1937. He continued his involvement with the Communist Party until the late 1940s, when he left it disillusioned. He moved to Chicago, where he worked as an editor for several publications. He died in 1997 in Arkansas at the age of 84.