BOSTON KING, Methodist preacher, and author; b. c. 1760 near Charleston, S.C.; d. 1802 in Sierra Leone.

Boston King was born a slave on Richard Waring’s plantation near Charleston. His father, who had been “stolen away from Africa when he was young,” was on good terms with Waring, and his mother also was well treated because of her skills as a nurse and seamstress. King was trained as a house servant but at the age of 16, still under Waring’s control, he was sent to a nearby town to be apprenticed as a carpenter. The time he spent learning his new trade was far from pleasant, for his employer often beat him “without mercy.” Fortunately, when the American revolution broke out Waring adhered to the rebels, which meant that if King could flee to the British he would gain freedom. His opportunity came when the British took Charleston in May 1780. Joining a mass movement of runaway slaves to the royal standard, King now “began to feel the happiness of liberty.”

The treatment provided by the British did not match the generosity of their offer of freedom. Squalid and overcrowded accommodation promoted disease, and King was one of the many to contract smallpox. After his recovery, he became useful to his benefactors. As a carpenter, he might have been one of that sizeable minority of black loyalists with specialized skills, many of whom plied their trades in the British service, but the absence of tools forced him to seek alternative employment as a servant. Like countless black loyalists, however, he soon was engaged in military action. By carrying dispatches through enemy lines he was responsible for the relief of 250 besieged British soldiers at Nelson’s Ferry (near Eutawville), S.C., and as a crew member on a British man-of-war, he helped capture a rebel ship in the Chesapeake Bay. Later he was taken and re-enslaved by the American navy but escaped for a second time to British safety threats to his freedom came not only from the rebels, for innumerable runaways were betrayed and sold as slaves by loyalist militia officers. Once King himself was taken by a militia captain, but his talent for escape saved him again.

As the war drew to a close, thousands of loyalists converged on New York City, King among them. While there he supported himself as a servant and casual laborer and married Violet, a fellow runaway who had escaped from a master in Wilmington, N.C. The publication of the preliminary peace agreement in late 1782 destroyed King’s comfort, for article 7 required the British to return all American property, including slaves. As King wrote later, the prospect of being returned to bondage filled the black loyalists with “inexpressible anguish and terror,” and their fears were certainly not diminished when former masters entered New York City and began seizing blacks in the streets and in their homes. At this critical point Sir Guy Carleton, commander-in-chief of British forces, announced that his interpretation of article 7 was that black loyalists were not, in fact, American property at the time of the agreement and so must be allowed to evacuate with other loyalists. Issued with certificates guaranteeing their freedom by Brigadier-General Samuel Birch, the city commandant, New York’s black refugees boarded the transport ships and had their names, descriptions, and personal histories recorded in the “Book of Negroes.” Between 26 April and 30 Nov. 1783, 3,000 black loyalists were shipped to Nova Scotia. King, described as a “Stout fellow” aged 23, embarked with his wife on L’Abondance and sailed for Port Roseway, recently renamed Shelburne, on 31 July.

The first loyalists had reached Port Roseway in May 1783, including a party of blacks who set to work clearing the town-site and preparing roads. At a discreet six miles from Shelburne, surveyor Benjamin Marston laid out a separate town-site for the blacks. King arrived there on 27 August in time to witness the survey and participate in the establishment of Birchtown, named for their New York protector. A muster held in January 1784 showed that Birchtown, with a population of 1,521 blacks, was the largest free black settlement in North America. Each of them received a town lot large enough for a garden, but the delay in granting farms forced them to continue to labor in Shelburne where construction assured plentiful employment.

A great religious revival occurred in Birchtown during the winter of 1783–84, part of a phenomenon seen all over Nova Scotia as the former slaves flocked to the churches for baptism. William Black, the Methodist evangelist, paid special attention to Birchtown, which contained the largest Methodist society in Nova Scotia. Even John Wesley remarked upon the religious enthusiasm of the Birchtown blacks, and in 1785 American Methodist Freeborn Garrettson was sent from Baltimore, Md, to assist in the harvest of souls. The first person in the settlement to be converted was King’s wife, Violet, who owed her deliverance from “evil tempers” to the preaching of Moses Wilkinson, a black loyalist and Birchtown’s leading Methodist. In early 1785 King, too, was converted. Describing his feelings at this time, King wrote: “All my doubts and fears vanished away: I saw, by faith, heaven opened to my view; and Christ and his angels rejoicing over me.” For the next few years, King preached in black settlements from Shelburne to Halifax. Owing to his and other preachers’ efforts, by 1790 black loyalists constituted one-quarter of Nova Scotia Methodists.

With most of his Birchtown neighbors, King worked in Shelburne, as a carpenter, and supplemented his income with his garden. Because they accepted lower wages, the blacks attracted the hostility of white workers, who launched a riot in July 1784 and attempted to drive them out of Shelburne. That issue disappeared as the whites were given farms, but by 1789 Shelburne’s economic difficulties created unemployment and abject distress for the blacks. King, appalled by the “poverty and distress” around him, left Birchtown and found work on a fishing boat operating out of Chedabucto Bay, where he continued to preach at every opportunity. In 1791 William Black, by the presiding elder of Nova Scotia’s Methodists, appointed King preacher to the black settlement at Preston near Halifax. The Preston black community was closely knit, and the preachers in the Anglican, Baptist, and Methodist chapels were its natural leaders. King knew comfort, at last, earning a decent living from his work in Preston and nearby Dartmouth, and enjoying the respect of his flock. His stay in Preston, however, was brief. Although satisfied with his life in Nova Scotia, he had a strong desire to spread “the knowledge of Christianity” amongst his African brothers, and in 1791 he joined other prominent Nova Scotia blacks, such as David George and Thomas Peters, in assisting John Clarkson of the Sierra Leone Company to recruit emigrants for a colony of free blacks in West Africa. The support he gave Clarkson in this endeavor yielded results: almost the entire black community of Preston, many of whom were motivated by the promise of free land and self-determination in Sierra Leone, joined in the exodus.

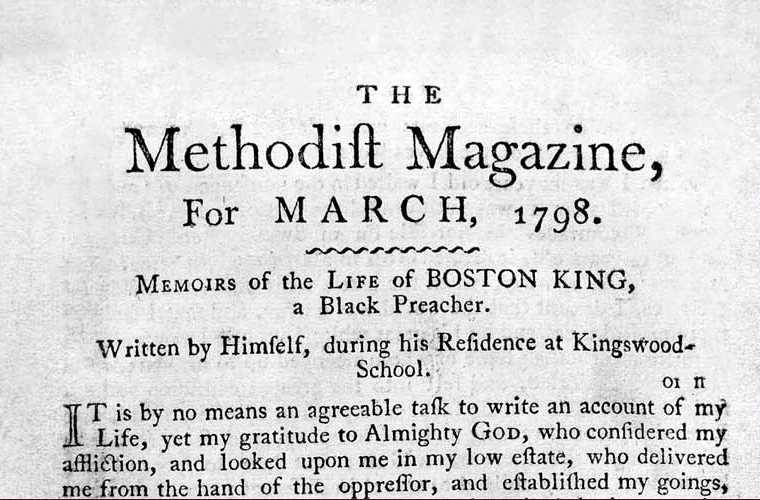

A fleet of 15 ships – King and the Preston blacks sailed on the Eleanor – left Nova Scotia for Sierra Leone in January 1792. After arriving in Freetown, Violet King succumbed to a fever epidemic, but King survived to establish a Methodist chapel. His ambition was fulfilled when in August 1793 the Sierra Leone Company appointed him teacher and missionary to the Africans on the Bullom shore, opposite Freetown, making him the first Methodist missionary in Africa. To improve his qualifications for this work, the company in March 1794 sent him to England, where he attended the Kingswood School near Bristol for two years. While there he wrote a memoir of his life to 1796. On his return to Africa in late September 1796, the company employed him as a teacher in Freetown and its vicinity, but he seems to have been dissatisfied with this work since his personal goal was to minister to the indigenous Africans. He soon left the colony for a company post located amongst the Sherbro people, some hundred miles south, where he probably resumed his missionary activity. He and his second wife both died there in 1802.

King was one of three black loyalists to leave a personal account of his experiences. John Marrant’s influential Narrative of the Lord’s wonderful dealings is his most important legacy, and David George still remembered as the founder of the black Baptist church in the Maritimes, published a revealing account of his life in the Baptist annual register. Boston King’s “Memoirs” was not a major literary or historical work, but through his reminiscences, it is possible to gain an impression of the life of the ordinary black loyalist during the American Revolution and in early Nova Scotia.