Dahomey, is a kingdom in western Africa that flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries in the region that is now southern Benin. According to tradition, at the beginning of the 17th century, three brothers vied for the kingdom of Allada, which, like neighboring Whydah (now Ouidah), had grown rich in the slave trade. When one of the brothers won control of Allada, the other two fled. One went southeast and founded Porto-Novo, on the coast east of Whydah. The other, Do-Aklin, went north to found the kingdom of Abomey, the core of future Dahomey. They all paid tribute to the powerful Yoruba kingdom of Oyo to the east.

Do-Aklin’s grandson Wegbaja (c. 1645–85) made Abomey into a powerful state. He was succeeded by Akaba (1685–1708) and Agaja (1708–32). Agaja, eager to buy arms from European traders on the Gulf of Guinea coast, conquered Allada (1724) and Whydah (1727), where European forts had already been established. The enlarged state was called Dahomey; Abomey, Allada, and Whydah were its provinces. Thriving on the sale of slaves to the Europeans, the Kingdom of Dahomey prospered and acquired new provinces under kings Tegbesu (1732–74), Kpengla (1774–89), and Agonglo (1789–97). After King Adandozan (1797–1818) was overthrown by the great Gezu (1818–58), Dahomey reached the high point of its power and fame.

The kingdom was a form of absolute monarchy unique in Africa. The king, surrounded by a magnificent retinue, was the unchallenged pinnacle of a rigidly stratified society of royalty, commoners, and slaves. He governed through a centralized bureaucracy staffed by commoners who could not threaten his authority. Each male official in the field had a female counterpart in court who monitored his activities and advised the king. Conquered territories were assimilated through intermarriage, uniform laws, and a common tradition of enmity to the Yoruba.

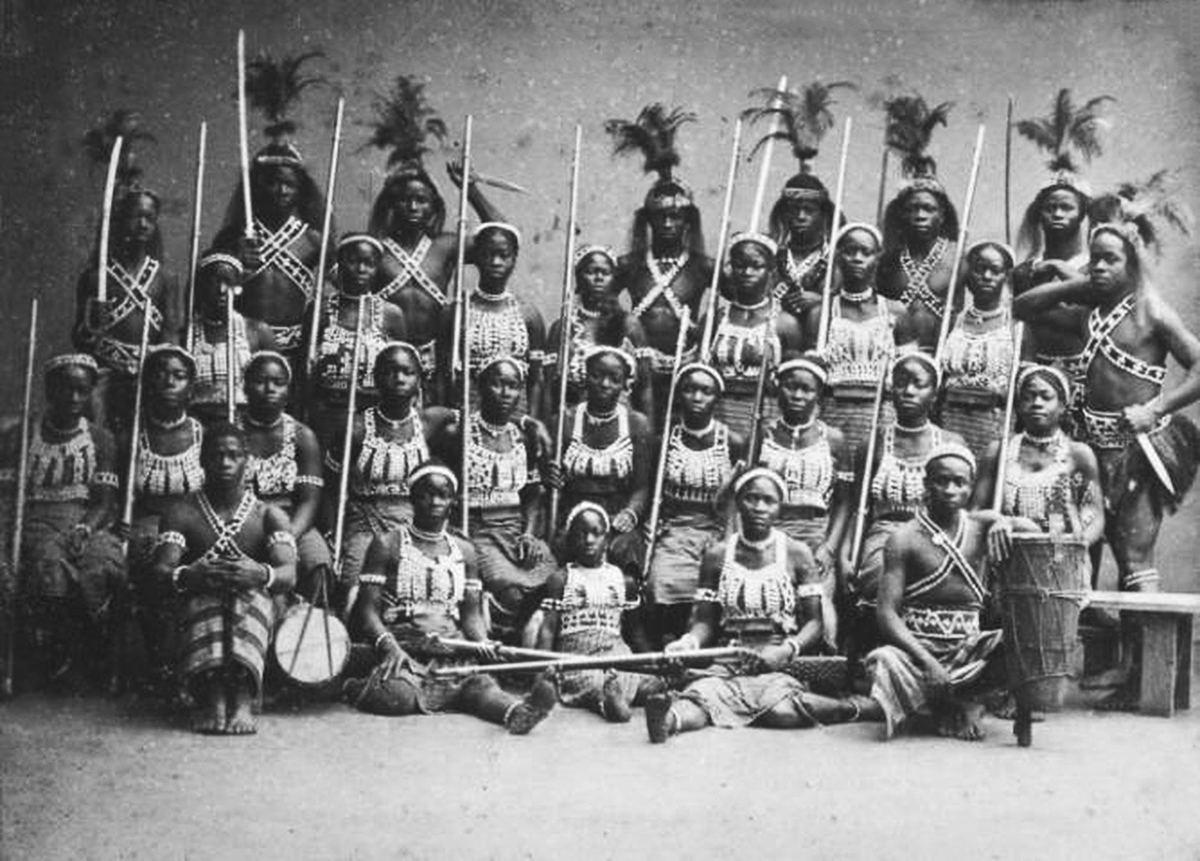

Dahomey was organized for war, not only to expand its boundaries but also to take captives as slaves. Slaves were either sold to the Europeans in exchange for weapons or kept to work on the royal plantations that supplied food for the army and court. From approximately 1680, a regular census of the population was taken as a basis for military conscription. Female soldiers, called Amazons by the Europeans, served as royal bodyguards when not in combat.

Gezu heightened the splendor of the court, encouraged the arts, and refined the bureaucracy. His armies freed Dahomey from the humiliation of paying tribute to Oyo. After about 1840, however, the kingdom’s fortunes changed as Britain succeeded in putting an end to the overseas slave trade. Gezu accomplished a smooth transition to palm oil exports; slaves, instead of being sold, were kept to work palm plantations. Palm oil was far less lucrative than slaves, however, and an economic decline followed under Gezu’s successor, Glele (1858–89).

When the French won control of Porto-Novo and Cotonou and attracted coastal trade there, commerce at Whydah collapsed. After the accession of Behanzin (1889–94) hostilities were precipitated. In 1892 a French expedition under Col. Alfred-Amédée Dodds defeated the Dahomeyans and established a protectorate. Behanzin was deported to the West Indies. His former kingdom was absorbed into the French colony of Dahomey, with its capital at Porto-Novo.