Henry Brown, born into slavery in Virginia around 1815, toiled on a tobacco plantation under the brutal weight of bondage. His life, already marked by hardship, was shattered in 1848 when he learned that his pregnant wife, Nancy, and their three children were to be sold to a slaveholder in North Carolina, tearing his family apart. The gut-wrenching news ignited a fierce determination in Brown—not only to reunite with his loved ones but to first secure his freedom. This resolve led him to orchestrate one of the most audacious escapes in the history of American slavery.

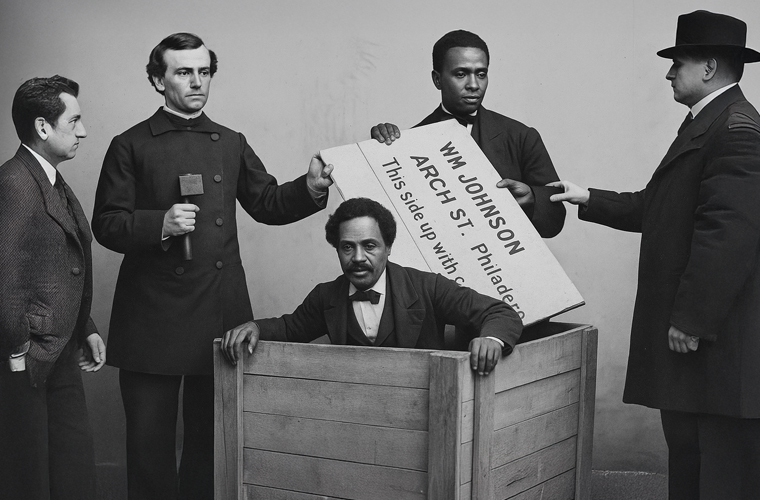

With the aid of two men named Smith—one a sympathetic white shoemaker and the other a free Black man—Brown devised a daring plan. He enlisted the services of the Adams Express Company, a private shipping firm, to transport him to freedom. His destination was the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, a hub of abolitionist activity where allies awaited his arrival. On March 23, 1849, Brown, fortified by his deep Christian faith and equipped with only a small bladder of water, a few biscuits, and a gimlet to bore air holes, squeezed his 5-foot-8, 200-pound frame into a wooden crate measuring just 3 feet long, 2 feet 8 inches deep, and 2 feet wide. Labeled as “dry goods,” the box was nailed shut, with Brown curled inside, enduring a suffocating, claustrophobic ordeal. For 27 grueling hours, he was jostled, flipped upside down, and nearly suffocated, surviving on sheer willpower and the faint hope of liberty. When the crate finally reached Philadelphia, abolitionists pried it open to find a sweat-soaked Brown, battered but alive. Emerging from his wooden prison, he reportedly greeted his rescuers with a triumphant, “How do you do, Gentlemen?” Overwhelmed with gratitude, he burst into a psalm of praise, earning the moniker Henry “Box” Brown from his awestruck liberators.

Brown’s extraordinary escape was a tale too gripping to remain untold. Despite warnings from prominent abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, who urged him to keep his method secret to allow others to replicate it, Brown chose a different path. Seeing an opportunity to secure his livelihood and share his story, he collaborated with allies to publish two autobiographies: Narrative of Henry Box Brown (1849) and a revised edition in 1851. He also took to the stage, performing in antislavery panorama plays across Boston and other northern cities. These theatrical productions, blending storytelling, music, and visual displays, captivated audiences and cemented Brown’s status as a celebrity in abolitionist circles. His performances not only spread the antislavery message but also showcased his charisma and creativity, transforming him into a symbol of resistance.

However, Brown’s newfound fame came at a cost. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act on August 30, 1850, endangered his freedom by empowering slave catchers to seize runaways in free states and return them to their enslavers. Fearing re-enslavement, Brown faced another perilous decision. Compounding his challenges, some abolitionists criticized him for not using his earnings to purchase the freedom of his wife and children in North Carolina when he had the chance. Whether due to financial constraints, strategic choices, or personal reasons, Brown’s decision strained his relationships with some in the abolitionist community, who saw his inaction as a moral failing. Feeling the weight of these pressures, Brown fled to England in 1850, where he found a new stage for his talents.

In England, Brown reinvented himself, performing his escape story for enthralled audiences across the country. He expanded his repertoire, becoming a mesmerist, magician, and showman, captivating crowds with his ingenuity and flair. During his 25-year sojourn, he met and married an Englishwoman named Jane, with whom he had a daughter, Annie. Incorporating his new family into his performances, Brown crafted a fresh identity, distancing himself from the pain of his enslaved past. His travels eventually took him to Ontario, Canada, where he and his family performed a show on February 26, 1889. Some accounts suggest Brown remained in Canada, possibly dying in Toronto in June 1897, though his final years remain shrouded in mystery.

Henry “Box” Brown’s story captivates not only for its breathtaking act of self-liberation but also for the complex, often troubling dimensions of his character. His escape demonstrated unparalleled courage and resilience, yet his choices—particularly his apparent abandonment of his enslaved family—paint a portrait of a man wrestling with the cost of freedom. Brown’s decision to forge a new life, leveraging his imagination and entrepreneurial spirit to survive in a hostile world, reveals the desperate measures required to escape