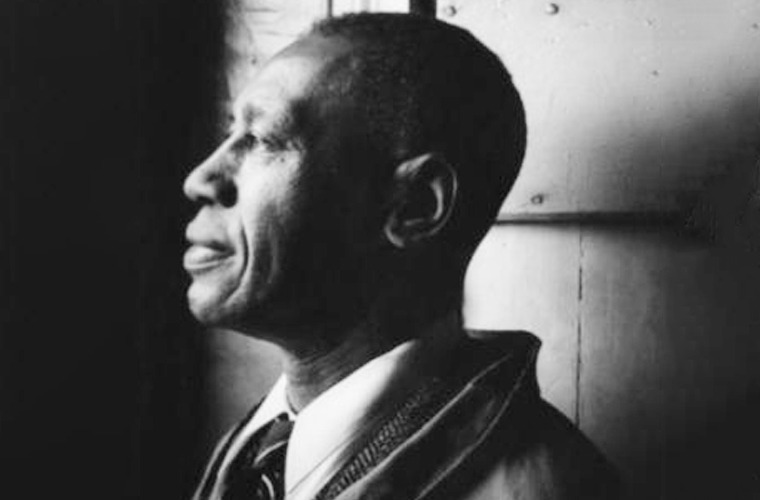

Horace Pippin, (born February 22, 1888, West Chester, Pennsylvania, U.S.—died July 6, 1946, West Chester), American folk painter known for his depictions of African American life and of the horrors of war.

Pippin’s childhood was spent in Goshen, New York, a town that sometimes appears in his paintings. There he drew horses at the local racetrack and, according to his own account, painted biblical scenes on frayed pieces of muslin. He was variously employed as an ironworker, junk dealer, and porter, until World War I when he served in the infantry. He was wounded in 1918 and discharged with a partially paralyzed right arm. He settled in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and eventually began to paint by burning designs into wood panels with a red-hot poker and then painting in the outlined areas.

His first large canvas was an eloquent protest against war, End of the War: Starting Home (1931–34), which was followed by other antiwar pictures, such as Shell Holes and Observation Balloon (1931) and many versions of Holy Mountain (all from c. 1944–45). His most frequently used theme centered on the African American experience, as seen in his series entitled Cabin in the Cotton (the mid-1930s) and his paintings of episodes in the lives of the antislavery leader John Brown and Abraham Lincoln. After the art world discovered Pippin in 1937, these pictures, in particular, brought him wide acclaim as the greatest black painter of his time. He enjoyed the enthusiastic support of art collectors Christian Brinton, Albert C. Barnes, and Edith Halpert, owner of the New York Gallery in New York City. His work was featured in the landmark exhibition “Masters of Popular Painting,” held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1938. Pippin also executed portraits and biblical subjects. His early works are characterized by their heavy impasto and restricted use of color. His later works are more precisely painted in a bolder palette.