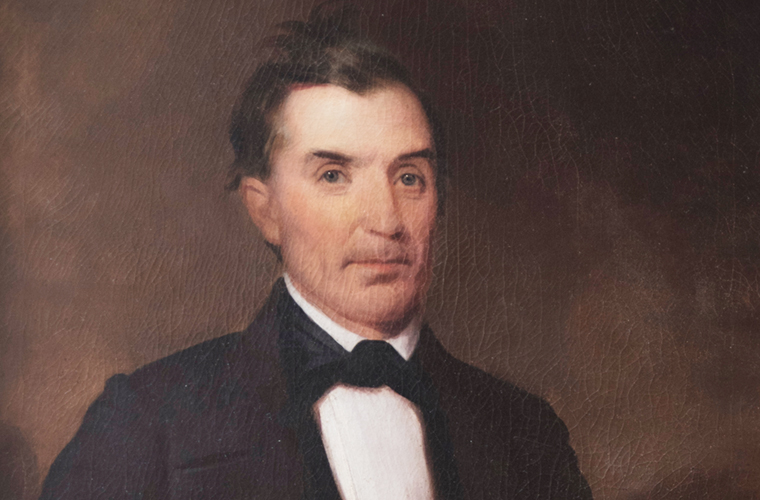

Isaac Franklin was an American slave trader who operated during the 19th century. He was born in 1789 in Virginia and began his career in the slave trade at a young age. Along with his business partner John Armfield, Franklin founded the slave trading firm Franklin and Armfield, which became one of the largest and most successful slave-trading enterprises in the United States.

Franklin’s role in the company involved purchasing enslaved people in the Upper South, including states like Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky, and then selling them for much higher prices in the Deep South, including states like Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. He was known for his ruthless tactics and willingness to separate families to maximize profits. The company’s operations disrupted the lives of countless enslaved people and contributed to the perpetuation of slavery in the United States.

Franklin was also involved in the forced migration of tens of thousands of enslaved people. He oversaw the transportation of enslaved people on ships that were often overcrowded and inhumane, resulting in many deaths during the journey. His actions and those of his company had a devastating impact on the lives of enslaved people and their descendants.

After the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Franklin’s trading operations were disrupted, and he died later that year. His legacy is a complicated one, as he was responsible for perpetuating one of the most brutal and inhumane practices in American history. His actions and those of his company have had a lasting impact on the lives of enslaved people and their descendants and serve as a reminder of the horrific atrocities committed during the era of slavery in the United States.