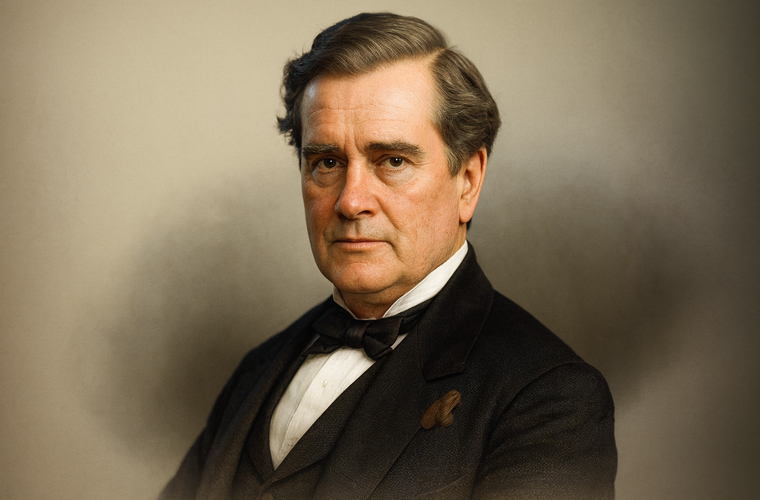

J. Marion Sims (1813–1883), often hailed as the “father of gynecology,” practiced medicine in central Alabama from 1835 to 1849, developing groundbreaking surgical techniques and tools that transformed gynecology. However, his legacy is deeply controversial due to the unethical nature of his experiments, particularly on enslaved women, which raises significant questions about his place in medical history.

Born on January 25, 1813, in Hanging Rock, South Carolina, Sims was the eldest of seven children in a family that ran a small farm and later an inn. He graduated from South Carolina College and earned a medical degree from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1835. After a failed practice in Lancaster, where two infant patients died, Sims moved to Macon County, Alabama, treating enslaved people on plantations. In 1836, he married Theresa Jones, with whom he had nine children. The couple relocated to Mt. Meigs and later Montgomery, where Sims built a thriving practice, owning 17 slaves and a dedicated medical facility by 1850.

In Montgomery, Sims pioneered treatments for vesico-vaginal fistulae (VVF) and recto-vaginal fistulae (RVF), painful conditions caused by prolonged labor that often left women incontinent and socially ostracized. Operating primarily on three enslaved women—Lucy, Betsey, and Anarcha—under the authority of plantation owners, Sims conducted experimental surgeries without anesthesia over nearly four years. Anarcha, for instance, endured 30 procedures after a traumatic three-day labor at age 17. Sims used opium to immobilize patients and developed tools like the duck-billed speculum, the Sims position, and the sigmoid catheter, which remain in use today. These innovations revolutionized gynecology, but the lack of consent and the immense suffering of his patients cast a dark shadow over his achievements.

Health issues, including malaria, prompted Sims to seek a better climate in the early 1850s, leading him to Philadelphia and New York City, where his techniques gained recognition. In 1852, he published a paper on VVF surgery and became the head surgeon at the Women’s Hospital of the State of New York, which was established to treat the condition. During the Civil War, Sims moved to Paris, where he treated European royalty, including the Empress of Austria, which further elevated his international fame. After returning to the U.S. post-war, he resigned from the Women’s Hospital in 1874 due to administrative conflicts but maintained a successful private practice. In 1876, he became president of the American Medical Association. Sims died in 1883, shortly after publishing his memoir, The Story of My Life.

Sims’s contributions to gynecology are undeniable, but his methods—performing experimental surgeries on enslaved women without consent—have drawn widespread condemnation. Scholars compare his practices to unethical experiments like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, highlighting how his work reinforced the institution of slavery. In 2018, reflecting this controversy, New York City relocated a statue of Sims from Central Park to Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, where he is buried. His legacy remains a complex intersection of medical innovation and profound ethical failure.