When enslaved Africans arrived in the Americas, they were often alone, separated from their family and community, and unable to communicate with those around them. The following description is from ‘The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

“When we arrived in Barbados (in the West Indies) many merchants and planters came on board and examined us. We were then taken to the merchant’s yard, where we were all pent up together like sheep in a fold. On a signal, the buyers rushed forward and chose those slaves they liked best.”

On arrival, the Africans were prepared for sale like animals. They were washed and shaved: sometimes their skins were oiled to make them appear healthy and increase their sale price. Depending on where they had arrived, the enslaved Africans were sold through agents by public auction or by a ‘scramble’, in which buyers simply grabbed whomever they wanted. Sales often involved measuring, grading, and intrusive physical examination.

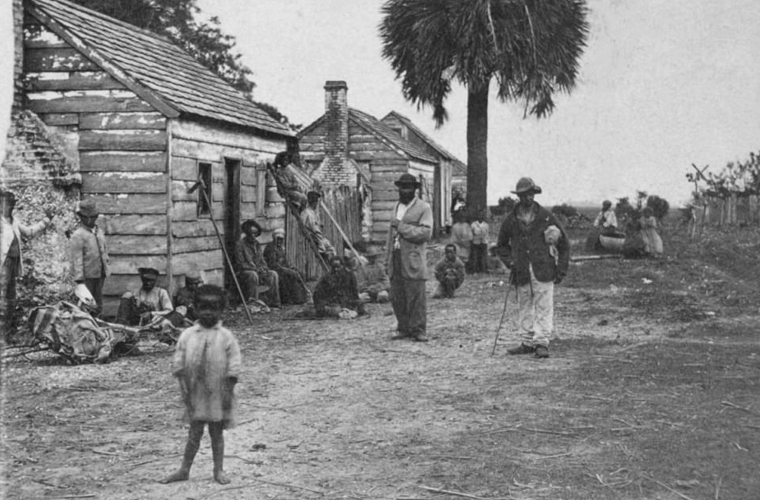

Sold, branded, and issued with a new name, the enslaved Africans were separated and stripped of their identity. In a deliberate process, meant to break their willpower and make them totally passive and subservient, the enslaved Africans were ‘seasoned.’ This means that, for a period of two to three years, they were trained to endure their work and conditions – obey or receive the lash. It was mental and physical torture. Life expectancy was short, on many plantations only 7-9 years. The high slave replacement figures were one piece of evidence used by the abolitionist, Anthony Benezet, to counter arguments that enslaved people benefitted from removal from Africa.

What was life like for the enslaved person?

It was a life of endless labor. They worked up to 18 hours a day, sometimes longer at busy periods such as harvest. There were no weekends or rest days. The dominant experience for most Africans was working on sugar plantations. In Jamaica, for example, 60% worked on the sugar plantations, and, by the early 19th century, 90% of enslaved Africans in Nevis, Montserrat, and Tobago toiled on sugar slave estates. The major secondary crop was coffee, which employed sizable numbers in Jamaica, Dominica, St Vincent, Grenada, St Lucia, Trinidad, and Demerara. Coffee plantations tended to be smaller than sugar estates and, because of their highland locations, were more isolated.

A few colonies grew no sugar. In Belize most enslaved Africans were woodcutters; on the Cayman Islands, Anguilla, and Barbuda, a majority of slaves lived on small mixed agricultural holdings; in the Bahamas, cotton cultivation was important for some decades. Even on a sugar-dominated island like Barbados, about one in ten slaves produced cotton, ginger, and aloe. Livestock ranching was important in Jamaica, where specialized pens emerged.

By the 1760s, on mainland North American plantations, half of the enslaved African people were occupied cultivating tobacco, rice, and indigo. Children under the age of six, a few elderly people, and some people with physical disabilities were the only people exempt from labor.

Individuals were allocated jobs according to gender, age, color, strength, and birthplace. Men dominated skilled trades and women generally came to dominate field gangs. Age determined when enslaved people entered the workforce, when they progressed from one gang to another, when field hands became drivers, and when field hands retired as watchmen. The offspring of planters and enslaved African women were often allocated domestic work or, in the case of men, to skilled trades.

Children were sent to work doing whatever tasks they were physically able. This could include cleaning, water carrying, stone picking, and collecting livestock feed. In addition to their work in the fields, women were used to carrying out the duties of servants, childminders, and seamstresses. Women could be separated from their children and sold to different ‘owners’ at any time.

Mary Prince, in her autobiography, described her experience of being enslaved and separated from her mother.

How did the plantation owners control the enslaved people?

The plantation owners may have controlled the work and physical well-being of enslaved people, but they could never control their minds. The enslaved people resisted at every opportunity and in many different ways uprising and keeping those enslaved under control was a priority of all plantation owners. The laws created to control enslaved populations were severe and illustrated the tensions that existed. The laws passed by the Islands‘ governing Assemblies are often referred to as the ‘Black Codes.’

Any enslaved person found guilty of committing or plotting serious offenses, such as violence against the plantation owner or destruction of property, was put to death. Beatings and whippings were a common punishment, as well as the use of neck collars or leg irons for less serious offenses, such as failure to work hard enough or insubordination, which covered many things.