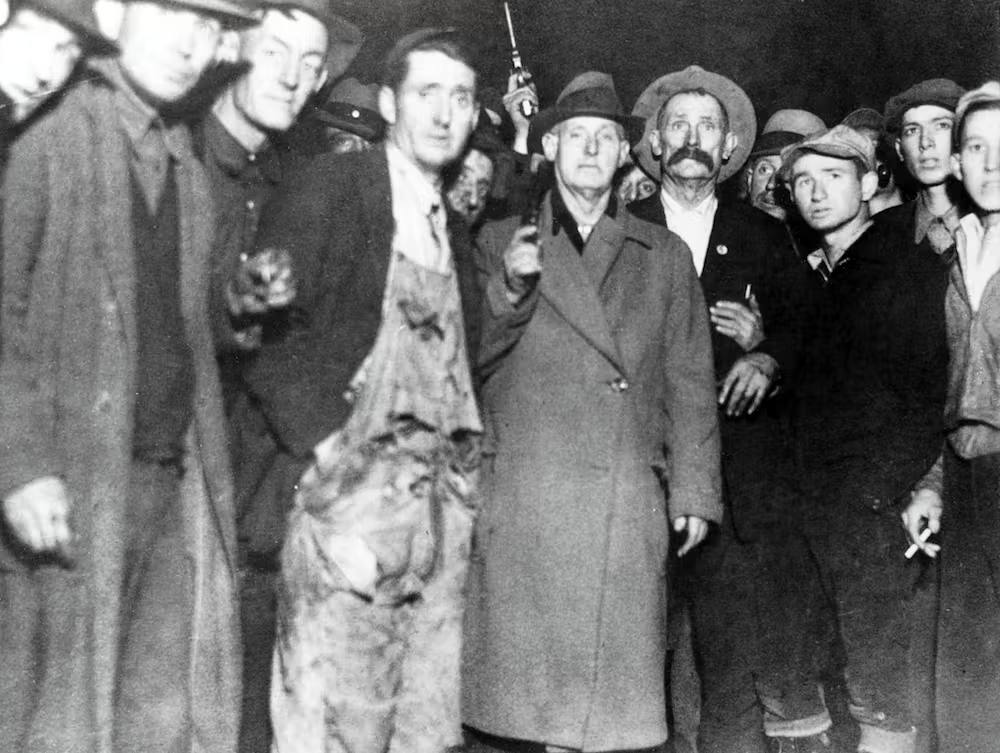

White lynch mobs in America murdered at least 4,467 people between 1883 and 1941, hanging, burning, dismembering, garroting, and blowtorching their victims. Their violence was widespread but not indiscriminate: About 3,300 of the lynched were black, according to the most recent count by sociologists Charles Seguin and David Rigby. The remaining dead were white, Mexican, of Mexican descent, Native American, Chinese or Japanese.

Such numbers, based on verifiable newspaper reports, represent a minimum. The full human toll of racial lynching may remain ever beyond reach. Religion was no barrier for these white murderers, as I’ve discovered in my research on Christianity and lynch mobs in the Reconstruction-era South. White preachers incited racial violence, joined the Ku Klux Klan, and lynched black people.

Buttressing white supremacy

When considering American racial terror, the first question to answer is not how a to lynch mob could kill a man of the cloth but why white lynch mobs killed at all. The typical answer from Southern apologists was that only black men who raped white women were targeted. In this view, lynching was “popular justice” – the response of an aggrieved community to a heinous crime. Journalists like Ida B. Wells and early sociologists like Monroe Work saw through that smokescreen, finding that only about 20% to 25% of lynching victims were alleged rapists. About 3% were women. Some were children.

Black people were lynched for murder or assault, or on suspicion that they committed those crimes. They could also be lynched for looking at a white woman or for bumping the shoulder of a white woman. Some were killed for being near or related to someone accused of the aforementioned offenses.

Identifying the dead is supremely difficult work. As sociologists, Amy Kate Bailey and Stewart Tolnay argue persuasively in their 2015 book “Lynched,” very little is known about lynching victims beyond their gender and race.

But by cross-referencing news reports with census data, scholars and civil rights organizations are uncovering more details. One might expect that mobs seeking to destabilize the black community would focus on the successful and the influential – people like preachers or prominent business owners.

Instead, lynching disproportionately targeted lower-status black people – individuals society would not protect, like the agricultural worker Sam Hose of Georgia and men like Henry Smith, a Texas handyman accused of raping and killing a three-year-old girl.

White preachers incited racial violence, joined the Ku Klux Klan, and lynched black people.

The rope and the pyre snuffed out primarily the socially marginal: the unemployed, the unmarried, the precarious – often not the prominent – who expressed any discontentment with racial caste. That’s because lynching was a form of social control. By killing workers with few connections who could be economically replaced – and doing so in brutal, public ways that struck terror into black communities – lynching kept white supremacy on track.

Fight from the front lines

So black ministers weren’t often lynching victims, but they could be targeted if they got in the way.

I.T. Burgess, a preacher in Putnam County, Florida, was hanged in 1894 after being accused of planning to instigate a revolt, according to a May 30, 1894, story in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper. Later that year, in December, the Constitution also reported, that Lucius Turner, a preacher near West Point, Georgia, was shot by two brothers for apparently writing an insulting note to their sister.

Ida B. Wells wrote in her 1895 editorial “A Red Record” about Reverend King, a minister in Paris, Texas, who was beaten with a Winchester Rifle and placed on a train out of town. His offense, he said, was being the only person in Lamar County to speak against the horrific 1893 lynching of the handyman Henry Smith.

In each of these cases, the victim’s profession was ancillary to their lynching. But preaching was not incidental to black pastors’ resistance to lynching. My dissertation research shows black pastors across the U.S. spoke out against racial violence during its worst period, despite the clear danger that it put them in.

Many, like the Washington, D.C., Presbyterian pastor Francis Grimke, preached to their congregations about racial violence. Grimke argued for comprehensive anti-racist education as a way to undermine the narratives that led to lynching.

Other pastors wrote furiously about anti-black violence.

Charles Price Jones, the founder of the Church of God (Holiness) in Mississippi, for example, wrote poetry affirming the African heritage of black Americans. Sutton Griggs, a black Baptist pastor from Texas, wrote novels that were, in reality, thinly veiled political treatises. Pastors wrote articles against lynching in their own denominational newspapers.

By any means necessary

Some white pastors decried racial terror, too. But others used the pulpit to instigate violence. On June 21, 1903, the white pastor of Olivet Presbyterian Church in Delaware used his religious leadership to incite a lynching. Preaching to a crowd of 3,000 gathered in downtown Wilmington, Reverend Robert A. Elwood urged the jury in the trial of George White – a black farm laborer accused of raping and killing a 17-year-old white girl, Helen Bishop – to pronounce White guilty speedily.

Otherwise, Elwood continued, according to June 23, 1903, New York Times article, that White should be lynched. He cited the Biblical text 1 Corinthians 5:13, which orders Christians to “expel the wicked person from among you.”

“The responsibility for lynching would be yours for delaying the execution of the law,” Elwood thundered, exhorting the jury. George White was dragged out of jail the next day, bound and burned alive in front of 2,000 people.

The following Sunday, a black pastor named Montrose W. Thornton discussed the week’s barbarities with his own congregation in Wilmington. He urged self-defense. “There is but one part left for the persecuted negro when charged with a crime and when innocent. Be a law unto yourself,” he told his parishioners. “Die in your tracks, perhaps drinking the blood of your pursuer.”

Newspapers around the country denounced both sermons. An editorial in the Washington Star said both pastors had “contributed to the worst passions of the mob.” By inciting lynching and advocating for self-defense, the editors judged, that Elwood and Thornton had “brought the pulpit into disrepute.”